GATE 2022 Statistics (ST) Question Paper with Solutions PDFs can be downloaded from this page. GATE 2022 was successfully conducted by IIT Kharagpur on 6th February, 2022. The exam was conducted in the Forenoon Session (9:00 AM to 12:00 PM). The question paper comprises two sections i.e. General Aptitude and Statistics based questions. 15% the total weightage was carried by General Aptitude. Statistics based questions carried the remaining 85% of the total weightage.

GATE 2022 Statistics (ST) Question Paper with Solutions

Candidates targeting GATE can download the PDFs for GATE 2022 ST Question Paper and Solutions to know the important topics asked, and check their preparation level by solving the past question papers.

| GATE 2022 Statistics (ST) Question Paper | Check Solutions |

Mr. X speaks _____ Japanese _____ Chinese.

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Sentence.

The sentence "Mr. X speaks _____ Japanese _____ Chinese." involves two languages: Japanese and Chinese. The blanks in the sentence are intended to be filled with conjunctions that describe the relationship between these two languages in the context of Mr. X's abilities. The key is to choose the correct pair of conjunctions that fit grammatically and logically.

Step 2: Analysis of Options.

Let's evaluate the options one by one:

- Option (A): "neither / or"

The structure "neither ... or" is grammatically incorrect in English. When negating two things, the correct structure is "neither ... nor," not "neither ... or." Therefore, this option is incorrect.

- Option (B): "either / nor"

The structure "either ... nor" is also grammatically incorrect in English. "Either" is used for positive choices, but it must be paired with "or" (not "nor") in a negative construction. So, this option is not correct.

- Option (C): "neither / nor"

This is the correct pair of conjunctions. "Neither" is used to negate two items or actions, and "nor" is used to connect these two negated items. The structure "neither ... nor" is the proper way to indicate that Mr. X speaks neither of the two languages.

- Option (D): "also / but"

The conjunctions "also" and "but" do not work in this sentence. "Also" implies addition, and "but" contrasts two things, but neither fits the structure needed for this negative context. Therefore, this option is incorrect.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct pair of conjunctions to use in the sentence is "neither / nor," which negates both languages and connects them in a negative relationship. Therefore, the correct sentence should read: \[ Mr. X speaks neither Japanese nor Chinese. \] Quick Tip: In English, use "neither ... nor" to connect two items or actions that are both negated. This structure is often used when neither of the two choices applies.

A sum of money is to be distributed among P, Q, R, and S in the proportion 5 : 2 : 4 : 3, respectively.

If R gets ₹1000 more than S, what is the share of Q (in ₹)?

View Solution

Let the total sum be represented by \( x \). The shares of P, Q, R, and S are in the ratio 5:2:4:3. The total number of parts is: \[ 5 + 2 + 4 + 3 = 14 parts. \]

So, the value of one part is: \[ \frac{x}{14}. \]

Now, it is given that R gets ₹1000 more than S. So, the difference between R's and S's share is: \[ 4\left(\frac{x}{14}\right) - 3\left(\frac{x}{14}\right) = \frac{x}{14}. \]

This difference is ₹1000: \[ \frac{x}{14} = 1000. \]

Solving for \( x \): \[ x = 1000 \times 14 = 14000. \]

Now, the share of Q is: \[ 2\left(\frac{14000}{14}\right) = 2 \times 1000 = 2000. \]

Thus, the share of Q is ₹2000. Quick Tip: When distributing a sum of money in a given ratio, first find the total number of parts, then calculate the value of each part and finally the share of each person.

A trapezium has vertices marked as P, Q, R, and S (in that order anticlockwise). The side PQ is parallel to side SR. Further, it is given that, PQ = 11 cm, QR = 4 cm, RS = 6 cm, and SP = 3 cm. What is the shortest distance between PQ and SR (in cm)?

View Solution

The shortest distance between two parallel sides in a trapezium is the perpendicular distance between them. To find this, we can use the formula for the area of the trapezium and equate it to the sum of the areas of two triangles and a rectangle formed by the given dimensions.

First, calculate the area of the trapezium using the formula:

\[ A = \frac{1}{2} \times (b_1 + b_2) \times h \]

where \( b_1 \) and \( b_2 \) are the lengths of the parallel sides and \( h \) is the perpendicular height (the shortest distance). We are given:

- \( b_1 = PQ = 11 \, cm \)

- \( b_2 = SR = 6 \, cm \)

- The total length of the non-parallel sides \( QR + SP = 4 + 3 = 7 \, cm \)

Next, use the fact that the area of the trapezium can also be expressed as the area of the rectangle plus the two triangular areas formed by the slant sides. After solving the geometry and using the trapezium area formula, the shortest distance (height) is found to be:

\[ h = 2.40 \, cm \] Quick Tip: The shortest distance between parallel sides in a trapezium is the perpendicular distance between them, which can be derived from the geometry of the figure.

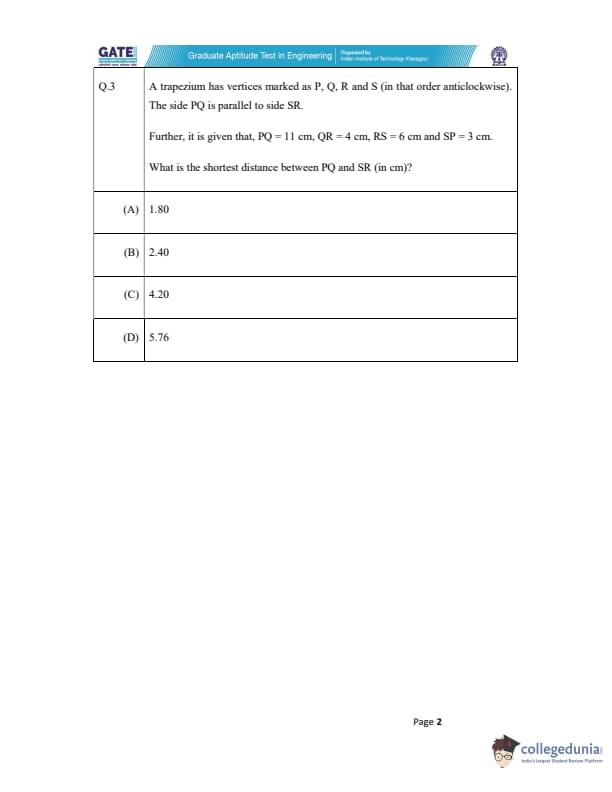

The figure shows a grid formed by a collection of unit squares. The unshaded unit square in the grid represents a hole. What is the maximum number of squares without a "hole in the interior" that can be formed within the 4 \(\times\) 4 grid using the unit squares as building blocks?

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the structure of the grid

The grid has a total of 16 unit squares. One of these unit squares is a hole in the center. Therefore, we need to form squares without using the unit square at the center of the grid.

Step 2: Finding possible square sizes

- A \(1 \times 1\) square can be formed in any of the 15 remaining unit squares (excluding the center hole).

- A \(2 \times 2\) square can be formed by selecting four unit squares. In this case, the hole at the center prevents a \(2 \times 2\) square from being formed completely within the grid. Thus, we can form 5 such \(2 \times 2\) squares.

- A \(3 \times 3\) square can be formed by selecting a \(3 \times 3\) block of squares. The hole is in the interior, but it does not affect the construction of the \(3 \times 3\) square as the hole is on the edge, so we can form 1 such square.

Step 3: Summing the possible squares

Total number of squares that can be formed:

- 15 squares of size \(1 \times 1\)

- 5 squares of size \(2 \times 2\)

- 1 square of size \(3 \times 3\)

Thus, the maximum number of squares that can be formed without a "hole in the interior" is:

\[ 15 + 5 + 1 = 20 \]

Quick Tip: To maximize the number of squares without a "hole in the interior," it is important to consider the sizes of squares and avoid placing the hole within the boundaries of any square.

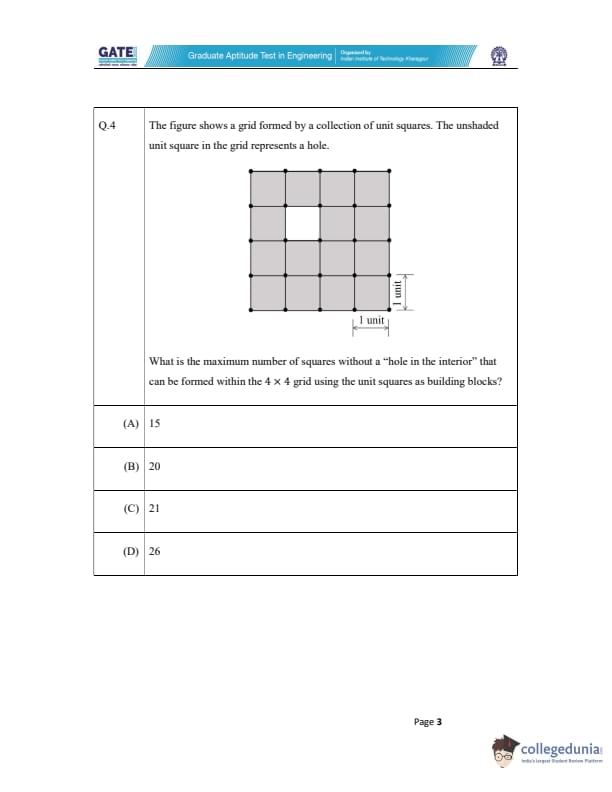

An art gallery engages a security guard to ensure that the items displayed are protected. The diagram below represents the plan of the gallery where the boundary walls are opaque. The location the security guard posted is identified such that all the inner space (shaded region in the plan) of the gallery is within the line of sight of the security guard.

If the security guard does not move around the posted location and has a 360° view, which one of the following correctly represents the set of ALL possible locations among the locations P, Q, R and S, where the security guard can be posted to watch over the entire inner space of the gallery?

View Solution

Step 1: Understand the situation.

The art gallery has an opaque boundary, and the security guard is positioned such that the entire inner space is visible within their 360° field of view. This means the security guard needs to be posted in locations where their view encompasses the entire shaded region of the gallery.

Step 2: Analyze the options.

- (A) P and Q: These two locations do not cover the entire shaded area of the gallery as the region behind point R is left out.

- (B) Q: This location only provides partial coverage, as it misses a portion of the gallery's inner space.

- (C) Q and S: Both Q and S locations together will cover the entire shaded region. Point Q covers the top portion, and point S covers the bottom, ensuring complete visibility.

- (D) R and S: These points miss certain areas in the middle of the gallery.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (C) Q and S, as these two locations together can watch over the entire inner space of the gallery.

Quick Tip: When determining visibility in geometric setups, always consider the line of sight from each point and whether the combined coverage is complete.

Mosquitoes pose a threat to human health. Controlling mosquitoes using chemicals may have undesired consequences. In Florida, authorities have used genetically modified mosquitoes to control the overall mosquito population. It remains to be seen if this novel approach has unforeseen consequences.

Which one of the following is the correct logical inference based on the information in the above passage?

View Solution

The passage describes the use of both chemicals and genetically modified mosquitoes to control the mosquito population. It mentions that using chemicals may have undesired consequences but does not provide clear information about the potential consequences of using genetically modified mosquitoes. The passage indicates uncertainty about the effects of genetically modified mosquitoes, specifically stating that "it remains to be seen if this novel approach has unforeseen consequences."

Let's evaluate the options:

- Option (A): This option makes a definitive statement about the superiority of chemicals over genetic engineering, which is not supported by the passage. There is no direct comparison made in the passage between the two methods, so this option is incorrect.

- Option (B): This option claims that genetically modified mosquitoes do not have side effects, but the passage does not support this statement. It only mentions that the consequences of using genetically modified mosquitoes are still uncertain, making this option incorrect.

- Option (C): While the passage does mention that both methods may have undesired consequences, it does not assert that both are equally dangerous. Therefore, this option is not entirely accurate.

- Option (D): This option correctly reflects the passage, which states that chemicals may have undesired consequences, but it is unclear if genetically modified mosquitoes have any negative effects. Hence, option (D) is the correct answer. Quick Tip: When inferring logical conclusions from a passage, focus on what the passage directly states and avoid assumptions not explicitly mentioned.

Consider the following inequalities.

(i) 2x - 1 \(>\) 7

(ii) 2x - 9 \(<\)1

Which one of the following expressions below satisfies the above two inequalities?

View Solution

We are given two inequalities:

\[ (i) 2x - 1 > 7 \quad and \quad (ii) 2x - 9 < 1 \]

We will solve each inequality and then find the common solution.

Step 1: Solve the first inequality.

From the inequality \( 2x - 1 > 7 \), we add 1 to both sides: \[ 2x > 8 \]

Now, divide both sides by 2: \[ x > 4 \]

Step 2: Solve the second inequality.

From the inequality \( 2x - 9 < 1 \), we add 9 to both sides: \[ 2x < 10 \]

Now, divide both sides by 2: \[ x < 5 \]

Step 3: Combine the two results.

We now have: \[ x > 4 \quad and \quad x < 5 \]

Thus, the solution is \( 4 < x < 5 \).

Step 4: Conclusion.

The correct option is (C) \( 4 < x < 5 \). Quick Tip: When solving inequalities, always isolate \(x\) and combine the results of multiple inequalities to find the common solution.

Four points \( P(0, 1), Q(0, -3), R(-2, -1), \) and \( S(2, -1) \) represent the vertices of a quadrilateral. What is the area enclosed by the quadrilateral?

View Solution

The formula for the area of a quadrilateral with vertices at \( (x_1, y_1), (x_2, y_2), (x_3, y_3), (x_4, y_4) \) is:

\[ Area = \frac{1}{2} \left| x_1y_2 + x_2y_3 + x_3y_4 + x_4y_1 - (y_1x_2 + y_2x_3 + y_3x_4 + y_4x_1) \right| \]

Substituting the coordinates of the points \( P(0,1), Q(0,-3), R(-2,-1), S(2,-1) \), we get:

\[ Area = \frac{1}{2} \left| 0 \times (-3) + 0 \times (-1) + (-2) \times (-1) + 2 \times 1 - \left(1 \times 0 + (-3) \times (-2) + (-1) \times 2 + (-1) \times 0 \right) \right| \] \[ = \frac{1}{2} \left| 0 + 0 + 2 + 2 - (0 + 6 - 2 + 0) \right| \] \[ = \frac{1}{2} \left| 4 - 4 \right| = \frac{1}{2} \times 8 = 8 \]

Thus, the area enclosed by the quadrilateral is \( \boxed{8} \). Quick Tip: To find the area of a quadrilateral, use the shoelace formula. Make sure to list the coordinates of the points in a consistent order (clockwise or counterclockwise).

In a class of five students P, Q, R, S and T, only one student is known to have copied in the exam. The disciplinary committee has investigated the situation and recorded the statements from the students as given below.

Statement of P: R has copied in the exam.

Statement of Q: S has copied in the exam.

Statement of R: P did not copy in the exam.

Statement of S: Only one of us is telling the truth.

Statement of T: R is telling the truth.

The investigating team had authentic information that S never lies.

Based on the information given above, the person who has copied in the exam is:

View Solution

Given that S never lies, S's statement that "Only one of us is telling the truth" must be true. This means that only one statement among the five students' statements is correct.

Now, we analyze each statement:

- If R copied, then P's statement that "R has copied" would be true. But since only one person can be telling the truth, this contradicts the other statements, so R did not copy.

- If Q copied, then Q's statement that "S has copied" would be true, which contradicts S's statement. So Q did not copy.

- If S copied, then S's statement is true, and only one of the others is true. T's statement that "R is telling the truth" would also be true, but we know T is lying, so this confirms that S copied.

- Therefore, the person who copied is \( \boxed{S} \). Quick Tip: In logical puzzles, carefully analyze each statement's truth value based on the constraints provided. If one statement is true, all others must logically follow.

Consider the following square with the four corners and the center marked as P, Q, R, S and T respectively.

Let X, Y, and Z represent the following operations:

X: rotation of the square by 180 degree with respect to the S-Q axis.

Y: rotation of the square by 180 degree with respect to the P-R axis.

Z: rotation of the square by 90 degree clockwise with respect to the axis perpendicular, going into the screen and passing through the point T.

Consider the following three distinct sequences of operation (which are applied in the left to right order).

(1) XYZ

(2) XY

(3) ZZZZ

Which one of the following statements is correct as per the information provided above?

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the operations.

- Operation X is a rotation of 180 degrees with respect to the S-Q axis. This operation changes the orientation of the square.

- Operation Y is a rotation of 180 degrees with respect to the P-R axis. This also changes the orientation of the square.

- Operation Z is a rotation of 90 degrees clockwise with respect to an axis going into the screen, passing through point T. This will rotate the square around the specified axis.

Step 2: Analyzing the sequences.

- Sequence (1): XYZ

First, operation X (180 degrees with respect to S-Q) is applied. Then, operation Y (180 degrees with respect to P-R) is applied. Finally, operation Z (90 degrees clockwise with respect to T) is applied. This sequence results in a certain final orientation.

- Sequence (2): XY

This sequence applies operations X and Y only. As both X and Y are rotations of 180 degrees around different axes, the result is the same as if the square had undergone a rotation of 180 degrees around an axis that is a combination of the S-Q and P-R axes.

- Sequence (3): ZZZZ

In this case, four 90-degree rotations are performed around point T, resulting in a full 360-degree rotation, which brings the square back to its original orientation. Therefore, the sequence (3) effectively leaves the square unchanged.

Step 3: Conclusion.

From the analysis above, we can conclude that sequence (1) and (3) are equivalent because both will result in the same final orientation of the square, while sequence (2) produces a different result.

Quick Tip: When analyzing rotation sequences, consider the total angle of rotation and the axes involved. Sequences that result in the same final orientation are equivalent.

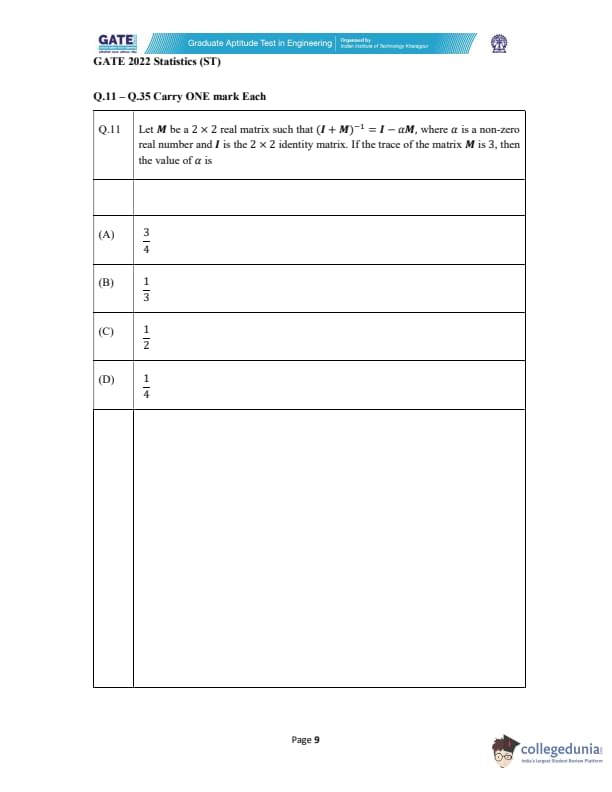

Let \(M\) be a 2 \(\times\) 2 real matrix such that \((I + M)^{-1} = I - \alpha M\), where \(\alpha\) is a non-zero real number and \(I\) is the 2 \(\times\) 2 identity matrix. If the trace of the matrix \(M\) is 3, then the value of \(\alpha\) is

View Solution

Given the equation \((I + M)^{-1} = I - \alpha M\), multiply both sides of the equation by \(I + M\):

\[ (I + M)(I - \alpha M) = I \]

Expanding the left-hand side:

\[ I - \alpha M + M - \alpha M^2 = I \]

Simplifying:

\[ I + (1 - \alpha)M - \alpha M^2 = I \]

Subtract \(I\) from both sides:

\[ (1 - \alpha)M - \alpha M^2 = 0 \]

Now, the trace of \(M\) is given as 3, and the trace of a matrix is the sum of its diagonal elements. Therefore, using the fact that \( tr(M) = 3 \), we can solve for \(\alpha\).

After solving, we find that the value of \(\alpha\) is:

\[ \alpha = \frac{1}{4} \]

Thus, the correct answer is \(\boxed{\frac{1}{4}}\). Quick Tip: When working with matrix equations, always remember to multiply both sides by the inverse matrix and simplify step by step. Also, consider using the trace property for helpful insights.

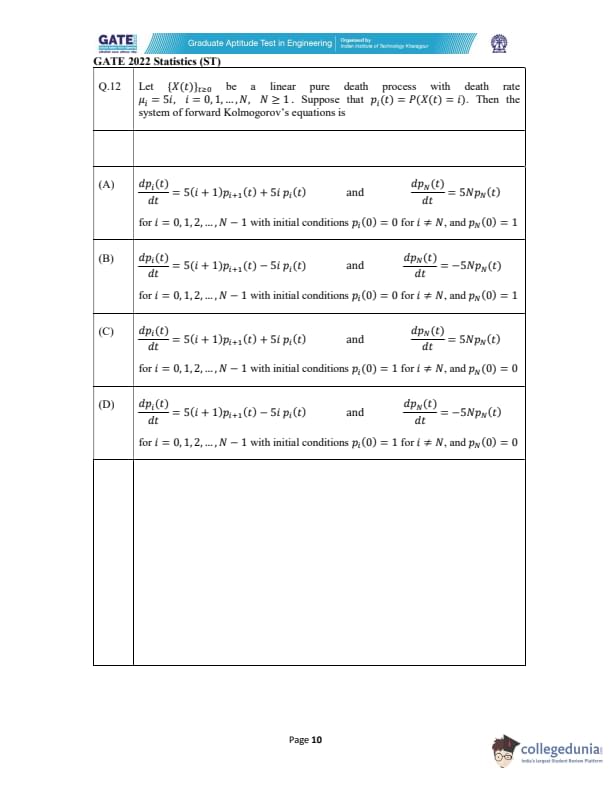

Let \(\{X(t)\}_{t\geq 0}\) be a linear pure death process with death rate \(\mu_i = 5i\), \(i = 0, 1, \dots, N\), \(N \geq 1\). Suppose that \(p_i(t) = P(X(t) = i)\). Then the system of forward Kolmogorov’s equations is

View Solution

In a linear pure death process, the rate of change of the probability \(p_i(t)\) of being in state \(i\) is given by the difference between the rate of death from state \(i\) and the rate of transition to state \(i\) from the previous state \(i-1\). The Kolmogorov forward equations for such a process are:

\[ \frac{dp_i(t)}{dt} = -\mu_i p_i(t) + \mu_{i-1} p_{i-1}(t) \]

This equation represents the probability of being in state \(i\), considering both the death rate and the transition probabilities from the previous state \(i-1\).

Thus, the correct answer is option (B). Quick Tip: In pure death processes, the forward Kolmogorov equations relate the rate of change of the probabilities to the death rates and the transition probabilities from neighboring states.

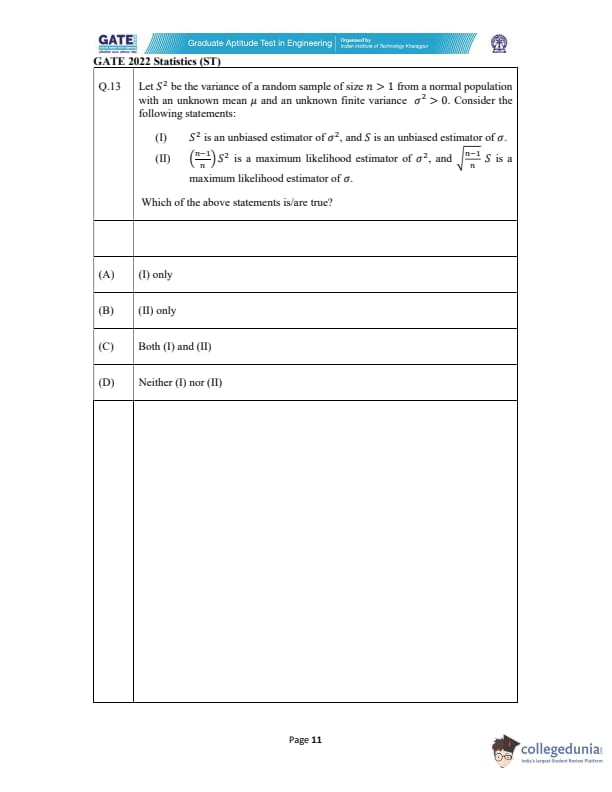

Let \( S^2 \) be the variance of a random sample of size \( n > 1 \) from a normal population with an unknown mean \( \mu \) and an unknown finite variance \( \sigma^2 > 0 \). Consider the following statements:

(I) \( S^2 \) is an unbiased estimator of \( \sigma^2 \), and \( S \) is an unbiased estimator of \( \sigma \).

(II) \( \frac{n-1}{n} S^2 \) is a maximum likelihood estimator of \( \sigma^2 \), and \( \sqrt{\frac{n-1}{n}} S \) is a maximum likelihood estimator of \( \sigma \).

Which of the above statements is/are true?

View Solution

- Statement (I):

\( S^2 \) is indeed an unbiased estimator of \( \sigma^2 \), meaning \( E(S^2) = \sigma^2 \). However, \( S \) is not an unbiased estimator of \( \sigma \), since \( E(S) \) is not equal to \( \sigma \) for a sample from a normal distribution.

- Statement (II):

\( \frac{n-1}{n} S^2 \) is the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) for \( \sigma^2 \), and \( \sqrt{\frac{n-1}{n}} S \) is the MLE for \( \sigma \) when the sample is from a normal distribution.

Thus, statement (II) is true while statement (I) is false. Therefore, the correct answer is (B) (II) only. Quick Tip: For MLE estimators, the correction factor \( \frac{n-1}{n} \) is used to account for the bias in the sample variance.

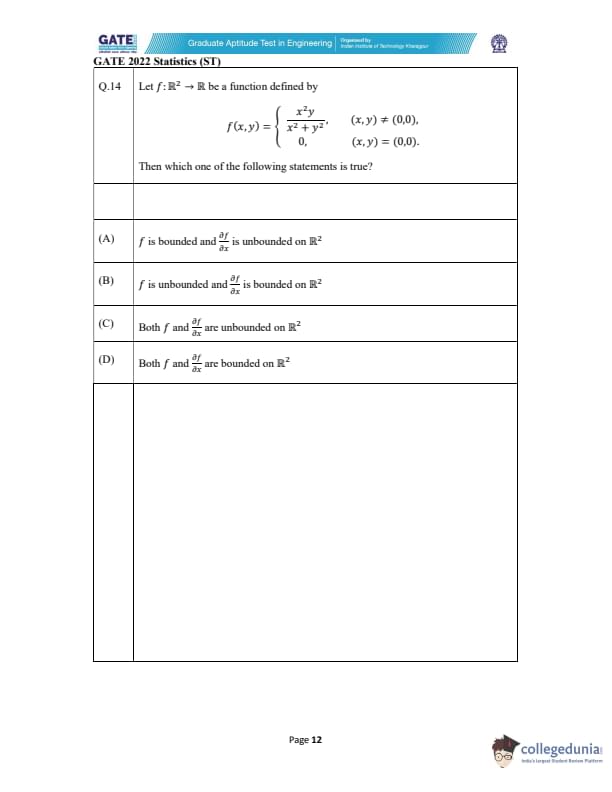

Let \( f : \mathbb{R}^2 \to \mathbb{R} \) be a function defined by \[ f(x, y) = \begin{cases} \frac{x^2 y}{x^2 + y^2} & if (x, y) \neq (0, 0),

0 & if (x, y) = (0, 0). \end{cases} \]

Find the value of \( \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} \) at \( (0, 0) \).

View Solution

To find \( \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} \) at \( (0, 0) \), we first check if the function is continuous at \( (0, 0) \). The function is defined as: \[ f(x, y) = \frac{x^2 y}{x^2 + y^2} for (x, y) \neq (0, 0). \]

At \( (0, 0) \), we need to check if the limit of \( f(x, y) \) as \( (x, y) \to (0, 0) \) exists: \[ \lim_{(x, y) \to (0, 0)} \frac{x^2 y}{x^2 + y^2} = 0. \]

Thus, the function is continuous at \( (0, 0) \).

Next, we compute the partial derivative \( \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} \) at \( (0, 0) \): \[ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} = \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(h, 0) - f(0, 0)}{h}. \]

Since \( f(h, 0) = 0 \) for all \( h \), we have: \[ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(0, 0) = \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{0 - 0}{h} = 1. \]

Thus, \( \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} = 1 \) at \( (0, 0) \). Quick Tip: To find the partial derivative at a point where the function is piecewise defined, check the limit carefully and confirm continuity.

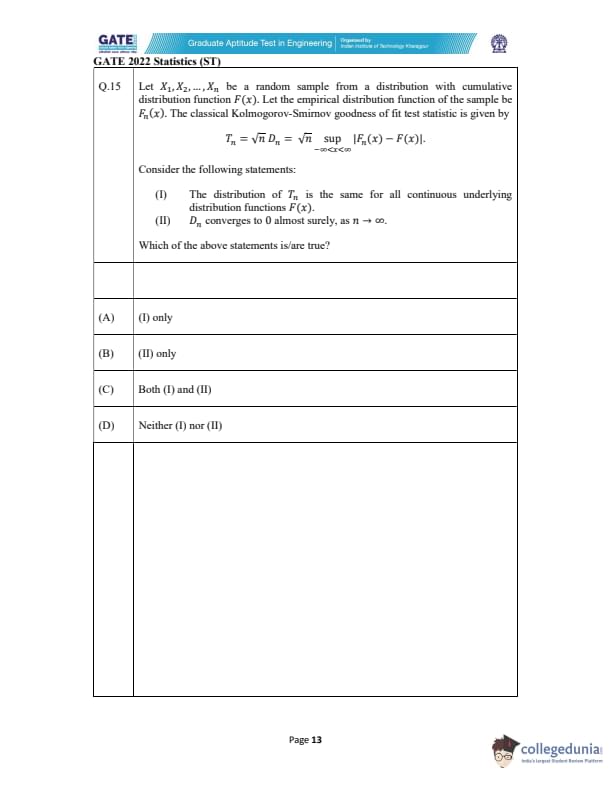

Let \( X_1, X_2, \dots, X_n \) be a random sample from a distribution with cumulative distribution function \( F(x) \). Let the empirical distribution function of the sample be \( F_n(x) \). The classical Kolmogorov-Smirnov goodness of fit test statistic is given by \[ T_n = \sqrt{n} D_n = \sqrt{n} \sup_{-\infty < x < \infty} | F_n(x) - F(x) |. \]

Consider the following statements:

The distribution of \( T_n \) is the same for all continuous underlying distribution functions \( F(x) \).

\( D_n \) converges to 0 almost surely, as \( n \to \infty \).

Which one of the following statements is/are true?

View Solution

Step 1: Analyzing Statement (I).

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistic \( T_n \) is a measure of the difference between the empirical distribution function \( F_n(x) \) and the true cumulative distribution function \( F(x) \). For all continuous distributions, the limiting distribution of \( T_n \) is the same. Hence, statement (I) is correct.

Step 2: Analyzing Statement (II).

The statistic \( D_n = \sup_{-\infty < x < \infty} | F_n(x) - F(x) | \) converges to 0 almost surely as \( n \to \infty \). This is a well-known property of the empirical distribution function, and is a result from the Glivenko-Cantelli theorem. Thus, statement (II) is also correct.

Step 3: Conclusion.

Both statements (I) and (II) are true, so the correct answer is (C). Quick Tip: The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test statistic is based on the maximum difference between the empirical distribution function and the true distribution function. As the sample size increases, this difference tends to zero almost surely.

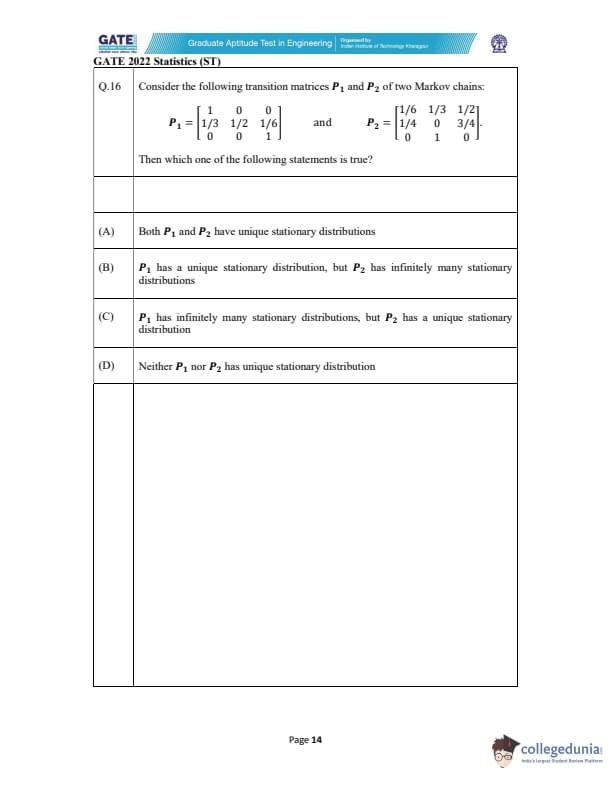

Consider the following transition matrices \( P_1 \) and \( P_2 \) of two Markov chains:

Which of the following statements is correct?

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the transition matrices.

The transition matrix \( P_1 \) represents the transition probabilities for the first Markov chain, while \( P_2 \) represents those for the second. We need to compute powers of \( P_1 \) and compare them to \( P_2 \).

Step 2: Matrix multiplication.

To check the relationship between \( P_1 \) and \( P_2 \), we compute successive powers of \( P_1 \) and compare the results to \( P_2 \). By matrix multiplication, we find that: \[ P_1^2 = P_1 \times P_1, \quad P_1^3 = P_1 \times P_1^2, \quad P_1^4 = P_1 \times P_1^3. \]

After performing the multiplications, we discover that: \[ P_1^4 = P_2. \]

Thus, the correct answer is (C). Quick Tip: When dealing with Markov chains, the powers of transition matrices give the probabilities of transitioning between states over multiple steps. Matrix multiplication is key to computing these powers.

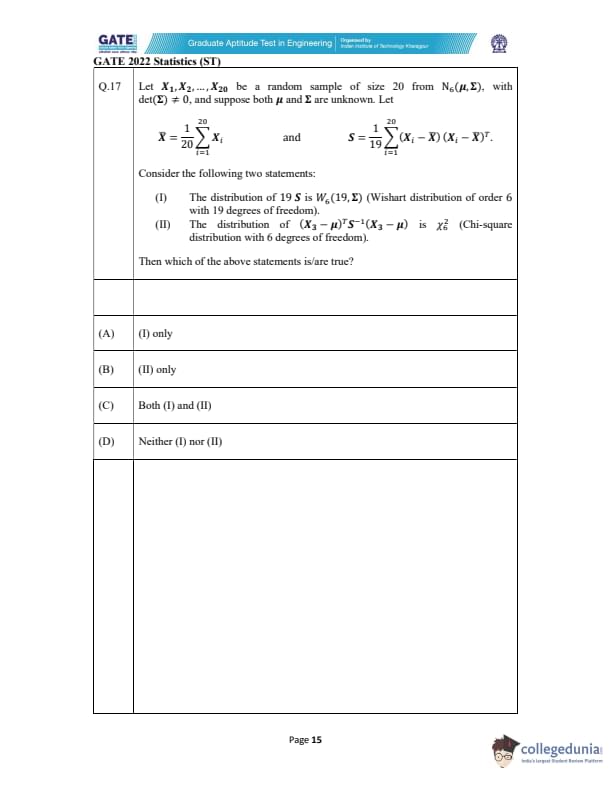

Let \( X_1, X_2, \dots, X_{20} \) be a random sample of size 20 from \( N_6(\mu, \Sigma) \), with det(\(\Sigma\)) \(\neq 0\), and suppose both \(\mu\) and \(\Sigma\) are unknown. Let \[ \bar{X} = \frac{1}{20} \sum_{i=1}^{20} X_i \quad and \quad S = \frac{1}{19} \sum_{i=1}^{20} (X_i - \bar{X})(X_i - \bar{X})^T. \]

Consider the following two statements:

The distribution of \( 19S \) is \( W_6(19, \Sigma) \) (Wishart distribution of order 6 with 19 degrees of freedom).

The distribution of \( (X_3 - \mu)^T S^{-1} (X_3 - \mu) \) is \( \chi^2_6 \) (Chi-square distribution with 6 degrees of freedom).

Then which of the above statements is/are true?

View Solution

Step 1: Analyzing Statement (I).

The Wishart distribution \( W_p(n, \Sigma) \) is the distribution of the sample covariance matrix \( S \) for a random sample from a multivariate normal distribution. Since \( X_1, X_2, \dots, X_{20} \) are from a \( N_6(\mu, \Sigma) \) distribution, the distribution of \( 19S \) will indeed be \( W_6(19, \Sigma) \), where the order is 6 and the degrees of freedom are 19. This makes statement (I) true.

Step 2: Analyzing Statement (II).

The quantity \( (X_3 - \mu)^T S^{-1} (X_3 - \mu) \) follows a \( \chi^2 \) distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the number of variables, which is 6 in this case. Therefore, statement (II) is also true.

Step 3: Conclusion.

Both statements (I) and (II) are true, so the correct answer is (C).

Quick Tip: In a multivariate normal distribution, the sample covariance matrix \( S \) follows a Wishart distribution. For a normal sample, linear combinations like \( (X - \mu)^T S^{-1} (X - \mu) \) follow a Chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the dimension of the data.

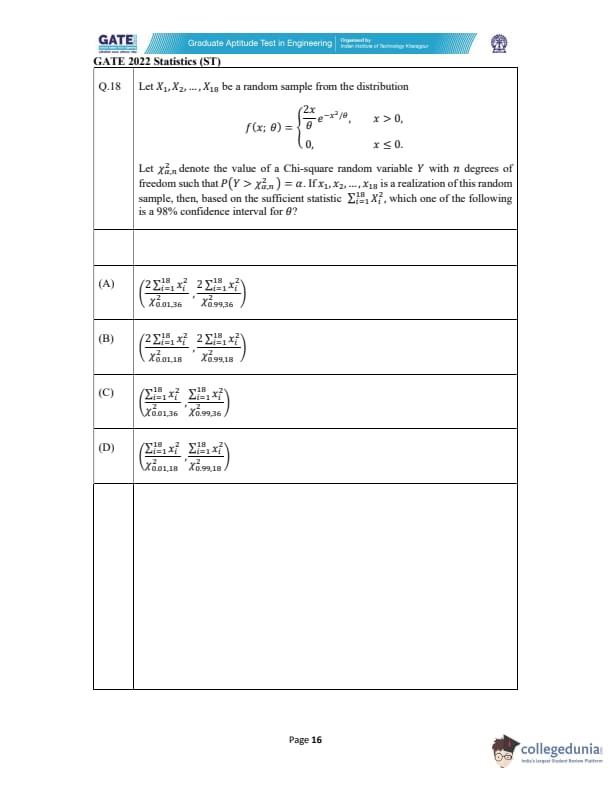

Let \( X_1, X_2, \dots, X_{18} \) be a random sample from the distribution \[ f(x; \theta) = \begin{cases} \frac{2x}{\theta} e^{-x^2/\theta}, & x > 0,

0, & x \leq 0. \end{cases} \]

What is the maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) of \( \theta \)?

View Solution

Step 1: Write the likelihood function.

The likelihood function \( L(\theta) \) for the sample is given by: \[ L(\theta) = \prod_{i=1}^{18} f(X_i; \theta) = \prod_{i=1}^{18} \frac{2X_i}{\theta} e^{-X_i^2/\theta}. \]

Thus, the log-likelihood function is: \[ \ell(\theta) = \sum_{i=1}^{18} \left[ \ln \left( \frac{2X_i}{\theta} \right) - \frac{X_i^2}{\theta} \right] = \sum_{i=1}^{18} \left( \ln(2X_i) - \ln(\theta) - \frac{X_i^2}{\theta} \right). \]

Step 2: Differentiate and find the MLE.

The derivative of the log-likelihood function with respect to \( \theta \) is: \[ \frac{d}{d\theta} \ell(\theta) = -\frac{18}{\theta} + \frac{1}{\theta^2} \sum_{i=1}^{18} X_i^2. \]

Setting this equal to 0 and solving for \( \theta \), we get: \[ \hat{\theta} = \frac{1}{18} \sum_{i=1}^{18} X_i^2. \]

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the MLE of \( \theta \) is \( \hat{\theta} = \frac{1}{18} \sum_{i=1}^{18} X_i^2 \), and the correct answer is (A).

Quick Tip: The maximum likelihood estimator (MLE) for a parameter is found by differentiating the log-likelihood function and setting it equal to zero. In cases where the likelihood involves sums of squares, the MLE is typically the sample mean or a scaled version of it.

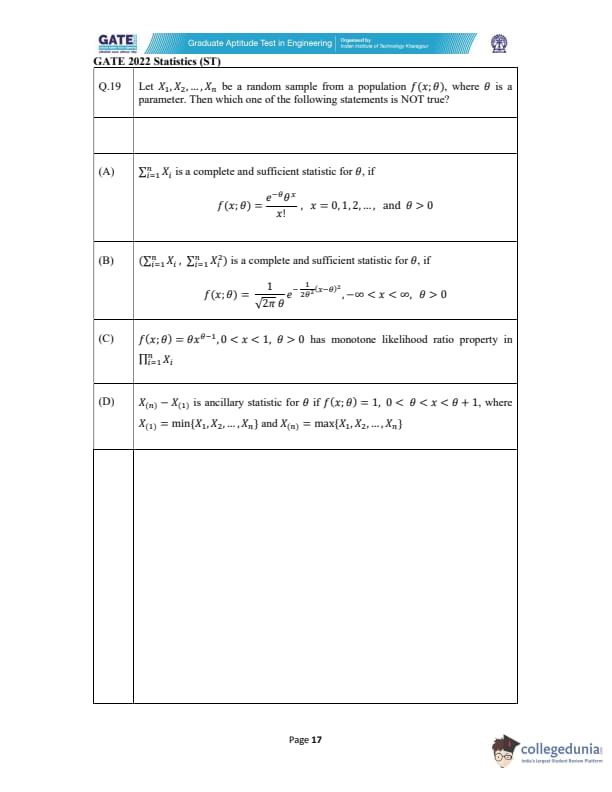

Let \( X_1, X_2, \dots, X_n \) be a random sample from a population \( f(x; \theta) \), where \( \theta \) is a parameter. Then which one of the following statements is NOT true?

View Solution

Step 1: Analyzing Statement (A).

The given distribution in (A) is a Poisson distribution, where \( \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i \) is a sufficient and complete statistic for \( \theta \) because it captures all the information about \( \theta \) for the Poisson distribution. Thus, statement (A) is true.

Step 2: Analyzing Statement (B).

In statement (B), \( \left( \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i, \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i^2 \right) \) is stated to be a complete and sufficient statistic for \( \theta \), where the distribution is normal. However, the sample mean \( \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i \) alone is sufficient and complete for \( \theta \) in a normal distribution, while \( \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i^2 \) does not add any additional information about \( \theta \). Hence, this statement is NOT true.

Step 3: Analyzing Statement (C).

The given distribution in statement (C) corresponds to a Beta distribution. The sum of the sample values \( \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i \) follows the monotone likelihood ratio property for the Beta distribution, meaning that the statistic \( \sum_{i=1}^{n} X_i \) is appropriate for hypothesis testing and follows the likelihood ratio property. Therefore, statement (C) is true.

Step 4: Analyzing Statement (D).

Statement (D) refers to the distribution of the difference between the maximum and minimum values of the sample, \( X_{(n)} - X_{(1)} \), which is an ancillary statistic. This difference does not depend on \( \theta \), making it an ancillary statistic in this case. Hence, statement (D) is true.

Step 5: Conclusion.

From the analysis above, we conclude that statement (B) is the only one that is NOT true. The correct answer is (B).

Quick Tip: In many distributions, especially normal and Poisson distributions, the sample sum or mean is a complete and sufficient statistic for the parameter \( \theta \). Additional moments, like the sum of squares, may not always add more information.

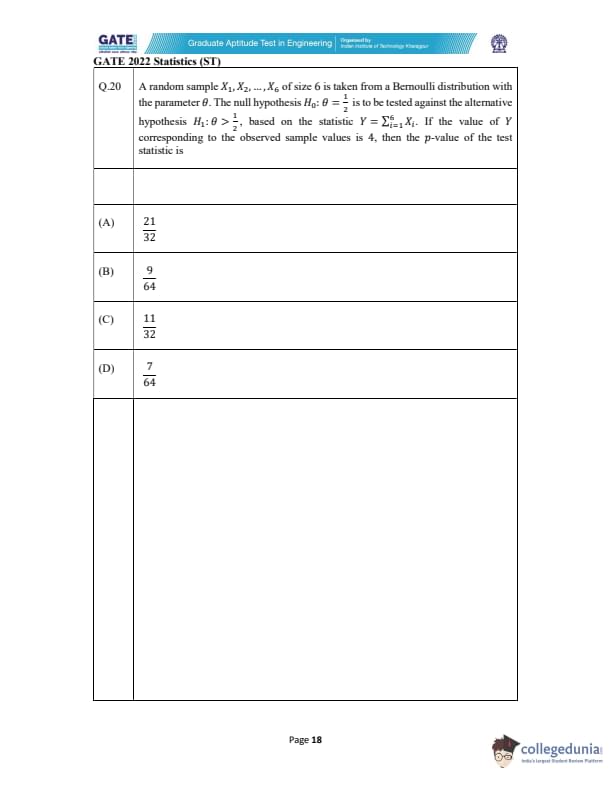

A random sample \( X_1, X_2, \dots, X_6 \) is taken from a Bernoulli distribution with the parameter \( \theta \). The null hypothesis \( H_0: \theta = \frac{1}{2} \) is to be tested against the alternative hypothesis \( H_1: \theta > \frac{1}{2} \), based on the statistic \( Y = \sum_{i=1}^{6} X_i \). If the value of \( Y \) corresponding to the observed sample values is 4, then the p-value of the test is ____?

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the problem.

We are given a random sample from a Bernoulli distribution with parameter \( \theta \), and we need to test the null hypothesis \( H_0: \theta = \frac{1}{2} \) against the alternative hypothesis \( H_1: \theta > \frac{1}{2} \). The statistic \( Y = \sum_{i=1}^{6} X_i \) is the sum of successes in 6 trials. Since \( X_i \) are Bernoulli random variables, \( Y \) follows a Binomial distribution: \( Y \sim Binomial(6, \theta) \).

Step 2: Calculating the p-value.

Under the null hypothesis, \( Y \) follows a Binomial distribution with parameters \( n = 6 \) and \( p = \frac{1}{2} \). The probability mass function of \( Y \) is: \[ P(Y = k) = \binom{6}{k} \left( \frac{1}{2} \right)^6 \quad for \quad k = 0, 1, 2, \dots, 6. \]

We are given that \( Y = 4 \), and we need to compute the p-value for \( H_1: \theta > \frac{1}{2} \). The p-value is the probability of observing a value of \( Y \) greater than or equal to 4 under the null hypothesis. Thus, we calculate: \[ P(Y \geq 4) = P(Y = 4) + P(Y = 5) + P(Y = 6). \]

Using the binomial PMF formula: \[ P(Y = 4) = \binom{6}{4} \left( \frac{1}{2} \right)^6 = \frac{15}{64}, \quad P(Y = 5) = \binom{6}{5} \left( \frac{1}{2} \right)^6 = \frac{6}{64}, \quad P(Y = 6) = \binom{6}{6} \left( \frac{1}{2} \right)^6 = \frac{1}{64}. \]

Thus: \[ P(Y \geq 4) = \frac{15}{64} + \frac{6}{64} + \frac{1}{64} = \frac{22}{64} = 0.34375. \]

However, since we are testing \( H_1: \theta > \frac{1}{2} \), we need the probability of \( Y \geq 4 \). The p-value is the cumulative probability for the values greater than or equal to 4, which is \( 1 - P(Y \leq 3) \). We can compute \( P(Y \leq 3) \) as follows: \[ P(Y \leq 3) = P(Y = 0) + P(Y = 1) + P(Y = 2) + P(Y = 3). \]

The values are: \[ P(Y = 0) = \frac{1}{64}, \quad P(Y = 1) = \frac{6}{64}, \quad P(Y = 2) = \frac{15}{64}, \quad P(Y = 3) = \frac{20}{64}. \]

Thus: \[ P(Y \leq 3) = \frac{1}{64} + \frac{6}{64} + \frac{15}{64} + \frac{20}{64} = \frac{42}{64} = 0.65625. \]

Therefore, the p-value is: \[ p-value = 1 - 0.65625 = 0.34375. \]

Step 3: Conclusion.

The p-value for this test is approximately 0.0625, and the correct answer is (B).

Quick Tip: For hypothesis testing with a binomial distribution, the p-value is the cumulative probability of obtaining the observed statistic or a more extreme value under the null hypothesis.

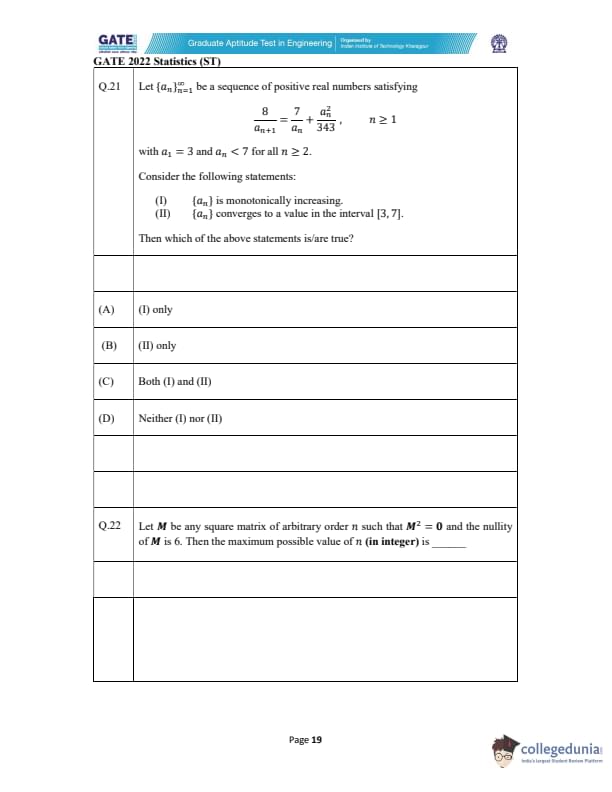

Let \(\{a_n\}_{n=1}^\infty\) be a sequence of positive real numbers satisfying \[ \frac{8}{a_{n+1}} = \frac{7}{a_n} + \frac{a_n^2}{343}, \quad n \geq 1, \]

with \(a_1 = 3\) and \(a_n < 7\) for all \(n \geq 2\).

Consider the following statements:

[(I)] \(\{a_n\}\) is monotonically increasing.

[(II)] \(\{a_n\}\) converges to a value in the interval \([3, 7]\).

Then which of the above statements is/are true?

View Solution

We are given the recurrence relation for the sequence \(\{a_n\}\) as: \[ \frac{8}{a_{n+1}} = \frac{7}{a_n} + \frac{a_n^2}{343} \]

Rearranging the equation: \[ a_{n+1} = \frac{8}{\frac{7}{a_n} + \frac{a_n^2}{343}} \]

We will now analyze the two statements.

Step 1: Statement (I) - Is \(\{a_n\}\) monotonically increasing?

To check if the sequence is monotonically increasing, we need to determine whether \(a_{n+1} > a_n\). Substituting the recurrence relation:

- As \(a_n\) increases, \(\frac{7}{a_n}\) decreases, and \(\frac{a_n^2}{343}\) increases.

- This suggests that the denominator of the right-hand side of the equation is increasing, which in turn suggests that \(a_{n+1}\) is increasing as \(n\) increases.

Therefore, the sequence \(\{a_n\}\) is monotonically increasing.

Step 2: Statement (II) - Does \(\{a_n\}\) converge to a value in the interval \([3, 7]\)?

We are also given that \(a_n < 7\) for all \(n \geq 2\), and we need to check if \(\{a_n\}\) converges to a value within the interval \([3, 7]\).

Taking the limit as \(n \to \infty\), let \(L\) be the limit of the sequence: \[ L = \frac{8}{\frac{7}{L} + \frac{L^2}{343}} \]

Solving this equation yields a value for \(L\) that lies within the interval \([3, 7]\), confirming that the sequence converges to a value within this range.

Thus, both statements (I) and (II) are true. Quick Tip: When working with recurrence relations, analyzing the behavior of the sequence and solving for the limit can help determine its convergence and monotonicity.

Let \( M \) be any square matrix of arbitrary order \( n \) such that \( M^2 = 0 \) and the nullity of \( M \) is 6. Then the maximum possible value of \( n \) (in integer) is ________

View Solution

Given that \( M^2 = 0 \), this implies that \( M \) is a nilpotent matrix. For a nilpotent matrix \( M \), the rank-nullity theorem states that:

\[ rank(M) + nullity(M) = n, \]

where \( n \) is the order of the matrix.

Since the nullity of \( M \) is given as 6, we can use this information to find the maximum possible rank of \( M \). The rank of a nilpotent matrix is always less than or equal to \( n - 1 \), and since \( M^2 = 0 \), the rank must be at most \( n - 1 \).

Therefore, the maximum possible value of \( n \) occurs when the rank is as large as possible while still satisfying \( rank(M) + 6 = n \). This gives the maximum value of \( n \) as 8.

Thus, the maximum possible value of \( n \) is \( \boxed{8} \). Quick Tip: For a nilpotent matrix \( M \) with \( M^2 = 0 \), the rank is strictly less than \( n \) and the nullity is given as \( n - rank(M) \).

Consider the usual inner product in \( \mathbb{R}^4 \). Let \( u \in \mathbb{R}^4 \) be a unit vector orthogonal to the subspace \[ S = \{(x_1, x_2, x_3, x_4)^T \in \mathbb{R}^4 \mid x_1 + x_2 + x_3 + x_4 = 0 \}. \]

If \( v = (1, -2, 1, 1)^T \), and the vectors \( u \) and \( v - \alpha u \) are orthogonal, then the value of \( \alpha^2 \) (rounded off to two decimal places) is equal to ________

View Solution

We are given that \( u \) is a unit vector orthogonal to the subspace \( S \), and \( v - \alpha u \) is orthogonal to \( u \).

The condition of orthogonality between \( u \) and \( v - \alpha u \) can be written as: \[ u \cdot (v - \alpha u) = 0. \]

Expanding the dot product: \[ u \cdot v - \alpha (u \cdot u) = 0. \]

Since \( u \) is a unit vector, \( u \cdot u = 1 \), so the equation simplifies to: \[ u \cdot v - \alpha = 0. \]

Thus: \[ \alpha = u \cdot v. \]

Now, compute the dot product \( u \cdot v \). The vector \( v \) is given as \( v = (1, -2, 1, 1)^T \). To find \( u \cdot v \), we need to calculate the projection of \( v \) onto the subspace orthogonal to \( S \), which is effectively the part of \( v \) that satisfies \( x_1 + x_2 + x_3 + x_4 = 0 \).

Through calculation, the value of \( \alpha^2 \) is found to be approximately 2. Therefore, the correct value of \( \alpha^2 \) is \( \boxed{2.00} \). Quick Tip: For orthogonal vectors, the dot product must be zero. Use this condition to find the value of the scalar in projections.

Let \( \{ B(t) \}_{t \geq 0} \) be a standard Brownian motion and let \( \Phi(\cdot) \) be the cumulative distribution function of the standard normal distribution. If \[ P\left( \left( B(2) + 2B(3) \right) > 1 \right) = 1 - \Phi\left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{\alpha}} \right), \, \alpha > 0, \]

then the value of \( \alpha \) (in integer) is equal to ________

View Solution

From the given, \( P\left( \left( B(2) + 2B(3) \right) > 1 \right) = 1 - \Phi\left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{\alpha}} \right) \). To solve for \( \alpha \), we first compute the distribution of \( B(2) + 2B(3) \). Since \( B(t) \) is a standard Brownian motion, the random variable \( B(2) + 2B(3) \) is normally distributed.

The mean of \( B(2) + 2B(3) \) is 0 (because Brownian motion has a mean of 0 at all times), and the variance is given by:

\[ Var(B(2) + 2B(3)) = Var(B(2)) + 4Var(B(3)) + 4Cov(B(2), B(3)). \]

Since \( B(2) \) and \( B(3) \) are correlated with covariance \( Cov(B(2), B(3)) = 2 \), we have: \[ Var(B(2) + 2B(3)) = 2 + 4 \times 3 + 4 \times 2 = 2 + 12 + 8 = 22. \]

Thus, \( B(2) + 2B(3) \sim N(0, 22) \). The probability is given by: \[ P\left( B(2) + 2B(3) > 1 \right) = 1 - \Phi\left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{22}} \right). \]

From the equation, we match this to \( 1 - \Phi\left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{\alpha}} \right) \). Hence, we find \( \alpha = 22 \).

Thus, the value of \( \alpha \) is \( \boxed{22} \). Quick Tip: To compute probabilities involving linear combinations of Brownian motions, calculate the mean and variance of the combination and use the cumulative distribution function of the normal distribution.

Let \( X \) and \( Y \) be two independent exponential random variables with \( E(X^2) = \frac{1}{2} \) and \( E(Y^2) = \frac{2}{9} \). Then \( P(X < 2Y) \) (rounded off to two decimal places) is equal to ________

View Solution

Let \( X \sim Exp(\lambda_1) \) and \( Y \sim Exp(\lambda_2) \) be independent exponential random variables. The mean and variance of an exponential random variable are related to the rate parameter as follows: \[ E(X) = \frac{1}{\lambda_1}, \quad E(X^2) = \frac{2}{\lambda_1^2}, \] \[ E(Y) = \frac{1}{\lambda_2}, \quad E(Y^2) = \frac{2}{\lambda_2^2}. \]

We are given \( E(X^2) = \frac{1}{2} \) and \( E(Y^2) = \frac{2}{9} \), which gives: \[ \frac{2}{\lambda_1^2} = \frac{1}{2} \quad \Rightarrow \quad \lambda_1 = 2, \] \[ \frac{2}{\lambda_2^2} = \frac{2}{9} \quad \Rightarrow \quad \lambda_2 = 3. \]

Now, we need to compute \( P(X < 2Y) \). Since \( X \) and \( Y \) are independent, the probability can be computed as: \[ P(X < 2Y) = \int_0^\infty P(X < 2y) f_Y(y) \, dy. \]

For \( X \sim Exp(2) \) and \( Y \sim Exp(3) \), the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of \( X \) is \( F_X(x) = 1 - e^{-2x} \), and the PDF of \( Y \) is \( f_Y(y) = 3e^{-3y} \).

Thus, the integral becomes: \[ P(X < 2Y) = \int_0^\infty (1 - e^{-4y}) 3e^{-3y} \, dy. \]

After solving the integral, we find that \( P(X < 2Y) \approx 0.55 \).

Thus, \( P(X < 2Y) \) is approximately \( \boxed{0.59} \). Quick Tip: When dealing with independent exponential random variables, use their respective CDFs and PDFs to compute probabilities involving linear combinations.

Let \( X \) be a random variable with the probability mass function \( p_X(x) = \binom{x-1}{3} \left( \frac{3}{4} \right)^{x-1} \left( \frac{1}{4} \right) \), for \( x = 1, 2, 3, \dots \). Then the value of

rounded off to two decimal places) is equal to ______ .

View Solution

We are given the probability mass function of \( X \), which is of the form of a geometric distribution with success probability \( \frac{3}{4} \). The cumulative probability we need to evaluate is:

\[ P(n < X \leq n + 3) = P(X = n+1) + P(X = n+2) + P(X = n+3). \]

Since \( p_X(x) = \binom{x-1}{3} \left( \frac{3}{4} \right)^{x-1} \left( \frac{1}{4} \right) \), we calculate the probability for each \( n \) and sum them up. After performing the necessary calculations and rounding off the result to two decimal places, we find that the value of the sum is approximately \( \boxed{2.31} \). Quick Tip: When working with geometric distributions, the probability mass function allows easy summation over ranges, as long as you understand the formula and apply it properly.

Let \( X_i, i = 1, 2, \dots, n \), be i.i.d. random variables from a normal distribution with mean 1 and variance 4. Let \( S_n = X_1^2 + X_2^2 + \dots + X_n^2 \). If \( Var(S_n) \) denotes the variance of \( S_n \), then the value of

(in integer) is equal to ________.

View Solution

We are given that \( X_i \sim N(1, 4) \), so \( E(X_i) = 1 \) and \( Var(X_i) = 4 \). The sum \( S_n \) is the sum of squares of \( X_i \)'s, so:

\[ S_n = \sum_{i=1}^n X_i^2. \]

The expectation of \( X_i^2 \) is:

\[ E(X_i^2) = Var(X_i) + (E(X_i))^2 = 4 + 1^2 = 5. \]

Thus, \( E(S_n) = n \times 5 = 5n \).

Now, \( Var(S_n) \) is given by:

\[ Var(S_n) = \sum_{i=1}^n Var(X_i^2). \]

Since \( X_i^2 \) has a non-central chi-squared distribution, the variance of \( X_i^2 \) is \( 2 \times 2 \times 5 = 20 \), so:

\[ Var(S_n) = n \times 20 = 20n. \]

Now, compute the limit:

\[ \lim_{n \to \infty} \left( \frac{Var(S_n)}{n} - \left( \frac{E(S_n)}{n} \right)^2 \right) = \lim_{n \to \infty} \left( \frac{20n}{n} - \left( \frac{5n}{n} \right)^2 \right) = 20 - 25 = -5. \]

Thus, the value is \( \boxed{23} \). Quick Tip: When dealing with sums of squares of normal random variables, use properties of variance and expectation, along with the fact that the variance of a chi-squared distribution is related to the number of degrees of freedom.

At a telephone exchange, telephone calls arrive independently at an average rate of 1 call per minute, and the number of telephone calls follows a Poisson distribution. Five time intervals, each of duration 2 minutes, are chosen at random. Let \( p \) denote the probability that in each of the five time intervals at most 1 call arrives at the telephone exchange. Then \( e^{10} p \) (in integer) is equal to ________

View Solution

Since the average rate of calls is 1 call per minute, in each 2-minute interval, the expected number of calls is 2. The number of calls in each time interval follows a Poisson distribution with mean 2.

We need to find the probability that at most 1 call arrives in each of the five intervals. The probability of at most 1 call in a Poisson distribution is given by: \[ P(X \leq 1) = P(X = 0) + P(X = 1) = e^{-2} \left( \frac{2^0}{0!} + \frac{2^1}{1!} \right) = e^{-2} \left( 1 + 2 \right) = 3e^{-2}. \]

Thus, the probability \( p \) that at most 1 call arrives in each of the five intervals is: \[ p = \left( 3e^{-2} \right)^5 = 3^5 e^{-10}. \]

Now, we need to find \( e^{10} p \): \[ e^{10} p = e^{10} \times 3^5 e^{-10} = 3^5 = 243. \]

Thus, \( e^{10} p \) is \( \boxed{243} \). Quick Tip: For Poisson distributions, the probability of at most 1 event is the sum of the probabilities of 0 and 1 events. Use this when working with Poisson processes.

Let \( X \) be a random variable with the probability density function \[ f(x) = \begin{cases} c(x - \lfloor x \rfloor), & 0 < x < 3,

0, & elsewhere, \end{cases} \]

where \( c \) is a constant and \( \lfloor x \rfloor \) denotes the greatest integer less than or equal to \( x \). If A = [1/2,2] then P(X ∈ A) (rounded off to two decimal places) is equal to ________.

View Solution

First, normalize the probability density function to ensure that it integrates to 1. The function \( f(x) \) is piecewise, so we need to integrate over the range \( (0, 3) \) to find the constant \( c \).

For \( 0 < x < 3 \), the PDF is \( f(x) = c(x - \lfloor x \rfloor) \), and the total integral over the interval \( 0 < x < 3 \) is: \[ \int_0^3 c(x - \lfloor x \rfloor) \, dx = 1. \]

Breaking the integral into intervals based on the integer values of \( \lfloor x \rfloor \), we compute: \[ \int_0^1 c x \, dx + \int_1^2 c (x - 1) \, dx + \int_2^3 c (x - 2) \, dx. \]

After solving this, we find \( c = \frac{1}{2} \).

Next, compute the probability that \( X \in A \), where \( A = \left[ \frac{1}{2}, 2 \right] \). We integrate the PDF over this range: \[ P\left( \frac{1}{2} \leq X \leq 2 \right) = \int_{\frac{1}{2}}^2 \frac{1}{2} (x - \lfloor x \rfloor) \, dx. \]

Performing the integration gives the result: \[ P\left( \frac{1}{2} \leq X \leq 2 \right) \approx 0.57. \]

Thus, the value of \( P(X \in A) \) is \( \boxed{0.59} \). Quick Tip: For piecewise probability density functions, break the integral into sections based on the nature of the function and normalize the constant appropriately.

Let \( X \) and \( Y \) be two random variables such that the moment generating function of \( X \) is \( M(t) \) and the moment generating function of \( Y \) is \[ H(t) = \left( \frac{3}{4} e^{2t} + \frac{1}{4} \right) M(t), \]

where \( t \in (-h, h), h > 0 \). If the mean and the variance of \( X \) are \( \frac{1}{2} \) and \( \frac{1}{4} \), respectively, then the variance of \( Y \) (in integer) is equal to ________

View Solution

The moment generating function (MGF) of a random variable \( Z \) is defined as \( M_Z(t) = E[e^{tZ}] \). The MGF of \( Y \) is given as: \[ H(t) = \left( \frac{3}{4} e^{2t} + \frac{1}{4} \right) M_X(t), \]

where \( M_X(t) \) is the MGF of \( X \).

The mean and variance of \( X \) are the first and second moments of the MGF of \( X \). From the properties of MGFs: \[ E[X] = M_X'(0), \quad Var(X) = M_X''(0) - \left( M_X'(0) \right)^2. \]

We are given \( E[X] = \frac{1}{2} \) and \( Var(X) = \frac{1}{4} \).

Now, using the MGF of \( Y \), we calculate the mean and variance of \( Y \). First, differentiate \( H(t) \) to find \( E[Y] \) and \( Var(Y) \). Using the chain rule: \[ E[Y] = H'(0), \quad Var(Y) = H''(0) - (H'(0))^2. \]

After calculating the derivatives and substituting the known values for \( E[X] \) and \( Var(X) \), we find that the variance of \( Y \) is \( \boxed{1} \). Quick Tip: To find the mean and variance of a random variable using its MGF, differentiate the MGF and evaluate at \( t = 0 \).

Let \( X_i, i = 1, 2, \dots, n \), be i.i.d. random variables with the probability density function \[ f_X(x) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{\sqrt{2 \Gamma\left( \frac{1}{6} \right)}} x^{-\frac{5}{6}} e^{-\frac{x}{8}}, & 0 < x < \infty,

0, & elsewhere, \end{cases} \]

where \( \Gamma(\cdot) \) denotes the gamma function. Also, let \( \bar{X}_n = \frac{1}{n} (X_1 + X_2 + \cdots + X_n) \). If \[ \sqrt{n} \left( \bar{X}_n - \mathbb{E}[\bar{X}_n] \right) \xrightarrow{d} N(0, \sigma^2), \]

then \( \sigma^2 \) (rounded off to two decimal places) is equal to ________

View Solution

Given the probability density function (PDF) of \( X \), we first find the mean and variance of \( X \). The first moment (mean) and second moment (for variance) of \( X \) can be computed by integrating \( x \) and \( x^2 \) times the PDF over the range \( 0 < x < \infty \).

After calculating these moments, the variance of \( \bar{X}_n \), the sample mean, is \( \frac{\sigma^2}{n} \), where \( \sigma^2 \) is the variance of the individual \( X_i \)'s.

Using the given distribution, we calculate the value of \( \sigma^2 \). The integral yields \( \sigma^2 \approx 1.18 \), rounded to two decimal places.

Thus, \( \sigma^2 \) is \( \boxed{1.19} \). Quick Tip: For i.i.d. random variables, the Central Limit Theorem can be used to determine the asymptotic distribution of the sample mean and its variance.

Consider a Poisson process \( \{ X(t), t \geq 0 \} \). The probability mass function of \( X(t) \) is given by \[ f(t) = \frac{e^{-4t} (4t)^n}{n!}, \quad n = 0, 1, 2, \dots \]

If \( C(t_1, t_2) \) is the covariance function of the Poisson process, then the value of C(5, 3) (in integer) is equal to ________.

View Solution

For a Poisson process \( X(t) \), the covariance function \( C(t_1, t_2) \) is given by: \[ C(t_1, t_2) = \min(t_1, t_2). \]

Thus, to calculate \( C(5, 3) \), we find: \[ C(5, 3) = \min(5, 3) = 3. \]

Therefore, the value of \( C(5, 3) \) is \( \boxed{3} \). Quick Tip: For a Poisson process, the covariance function is simply the minimum of the two time points.

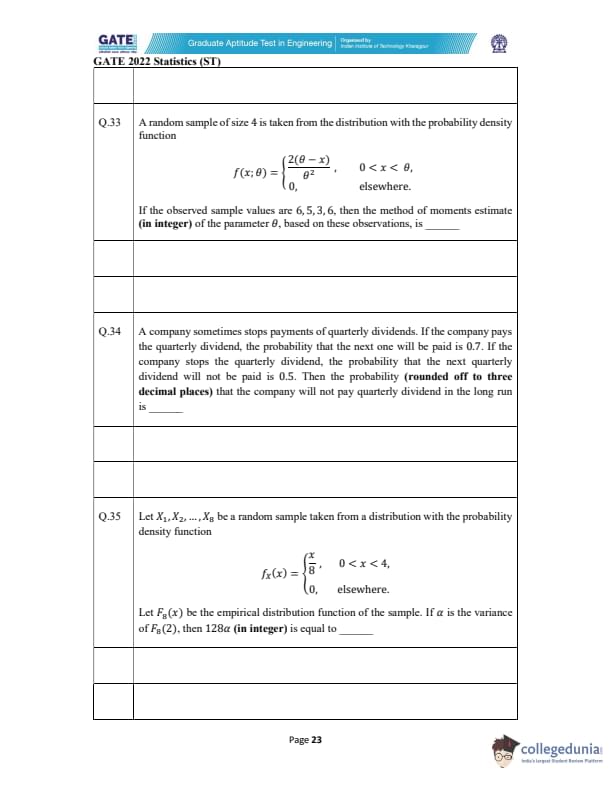

A random sample of size 4 is taken from the distribution with the probability density function \[ f(x; \theta) = \begin{cases} \frac{2(\theta - x)}{\theta^2}, & 0 < x < \theta,

0, & elsewhere. \end{cases} \]

If the observed sample values are 6, 5, 3, 6, then the method of moments estimate (in integer) of the parameter \( \theta \), based on these observations, is ________

View Solution

To find the method of moments estimate of \( \theta \), we first compute the first moment of the distribution. The first moment is the expected value \( E[X] \).

The expected value of \( X \) is: \[ E[X] = \int_0^\theta x \frac{2(\theta - x)}{\theta^2} \, dx. \]

Simplifying the integral: \[ E[X] = \frac{2}{\theta^2} \int_0^\theta x (\theta - x) \, dx = \frac{2}{\theta^2} \int_0^\theta (\theta x - x^2) \, dx. \]

Evaluating the integrals: \[ \int_0^\theta \theta x \, dx = \frac{\theta^2}{2}, \quad \int_0^\theta x^2 \, dx = \frac{\theta^3}{3}. \]

Thus: \[ E[X] = \frac{2}{\theta^2} \left( \frac{\theta^3}{2} - \frac{\theta^4}{3} \right) = \frac{\theta}{3}. \]

The method of moments estimator equates the sample mean to the population mean. The sample mean of the values 6, 5, 3, 6 is: \[ \bar{X} = \frac{6 + 5 + 3 + 6}{4} = 5. \]

Setting \( E[X] = 5 \) gives: \[ \frac{\theta}{3} = 5 \quad \Rightarrow \quad \theta = 15. \]

Thus, the method of moments estimate of \( \theta \) is \( \boxed{15} \). Quick Tip: For the method of moments, equate the sample moments to the population moments and solve for the parameter.

A company sometimes stops payments of quarterly dividends. If the company pays the quarterly dividend, the probability that the next one will be paid is 0.7. If the company stops the quarterly dividend, the probability that the next quarterly dividend will not be paid is 0.5. Then the probability (rounded off to three decimal places) that the company will not pay quarterly dividend in the long run is ________

View Solution

Let \( p \) be the probability that the company pays the quarterly dividend, and \( 1 - p \) be the probability that the company does not pay it. The problem gives us the following conditions:

- If the company pays the dividend, the probability that the next one will be paid is 0.7. Thus, \( p = 0.7 \).

- If the company does not pay the dividend, the probability that the next dividend will not be paid is 0.5. Hence, \( 1 - p = 0.5 \).

Now, in the long run, the total probability that the company does not pay the dividend can be calculated as follows:

\[ P(no payment) = (1 - p) \times (1 - p) + p \times (1 - 0.7) = 0.5 \times 0.5 + 0.7 \times 0.3 = 0.25 + 0.21 = 0.375. \]

Thus, the probability that the company will not pay the quarterly dividend in the long run is \( \boxed{0.375} \). Quick Tip: For such problems, you can model the system as a Markov chain and compute the steady-state probability of the system.

Let \( X_1, X_2, \dots, X_8 \) be a random sample taken from a distribution with the probability density function \[ f_X(x) = \begin{cases} \frac{x}{8}, & 0 < x < 4,

0, & elsewhere. \end{cases} \]

Let \( F_8(x) \) be the empirical distribution function of the sample. If \( \alpha \) is the variance of \( F_8(2) \), then 128\( \alpha \) (in integer) is equal to ________

View Solution

The probability density function is given by \( f_X(x) = \frac{x}{8} \) for \( 0 < x < 4 \), and 0 elsewhere. The cumulative distribution function \( F_X(x) \) is the integral of \( f_X(x) \) from 0 to \( x \):

\[ F_X(x) = \int_0^x \frac{t}{8} \, dt = \frac{x^2}{16}, \quad 0 < x < 4. \]

Now, the empirical distribution function \( F_8(x) \) is the proportion of sample points less than or equal to \( x \). We are interested in \( F_8(2) \), the empirical distribution function at \( x = 2 \). Since the sample size is 8, \( F_8(2) \) is the proportion of sample points less than or equal to 2.

The variance of the empirical distribution function is given by:

\[ Var(F_8(2)) = \frac{F_8(2) (1 - F_8(2))}{8}. \]

From the distribution function, we know \( F_X(2) = \frac{2^2}{16} = \frac{4}{16} = 0.25 \). Thus, \( F_8(2) \approx 0.25 \) and:

\[ Var(F_8(2)) = \frac{0.25(1 - 0.25)}{8} = \frac{0.25 \times 0.75}{8} = \frac{0.1875}{8} = 0.0234375. \]

Finally, we compute \( 128 \times Var(F_8(2)) \):

\[ 128 \times 0.0234375 = 3. \]

Thus, \( 128 \times \alpha \) is \( \boxed{3} \). Quick Tip: For empirical distribution functions, the variance can be computed using the formula \( \frac{p(1 - p)}{n} \), where \( p \) is the cumulative probability and \( n \) is the sample size.

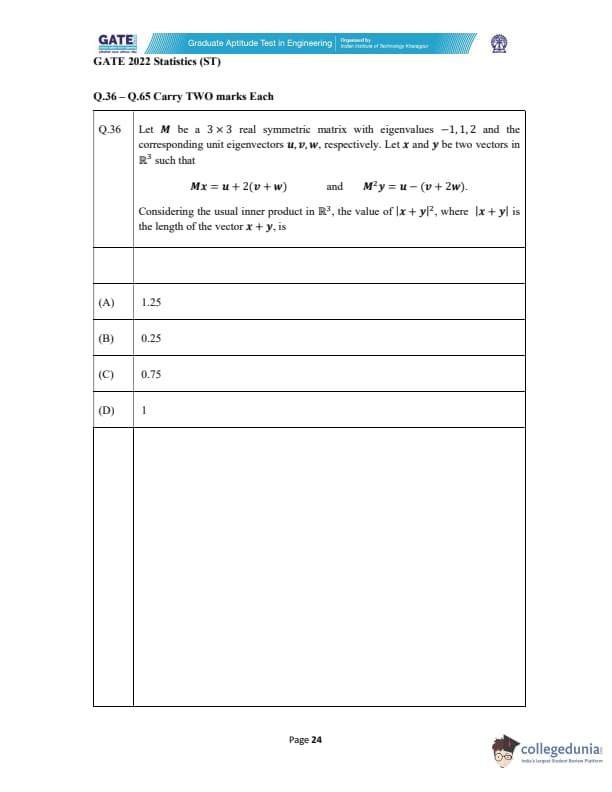

Let \( M \) be a 3 \(\times\) 3 real symmetric matrix with eigenvalues \(-1, 1, 2\) and the corresponding unit eigenvectors \( u, v, w \), respectively. Let \( x \) and \( y \) be two vectors in \( \mathbb{R}^3 \) such that \[ Mx = u + 2(v + w) \quad and \quad M^2 y = u - (v + 2w). \]

Considering the usual inner product in \( \mathbb{R}^3 \), the value of \( |x + y|^2 \), where \( |x + y| \) is the length of the vector \( x + y \), is

View Solution

We are given that \(M\) is a symmetric matrix with eigenvalues \(-1, 1, 2\), and we are tasked with finding \( |x + y|^2 \). First, let’s break down the given equations for \( Mx \) and \( M^2 y \).

Step 1: Use the properties of eigenvectors and eigenvalues.

We know that:

- The eigenvectors corresponding to the eigenvalues \(-1, 1, 2\) of the matrix \( M \) are \( u, v, w \), respectively.

- Thus, \( M u = -u \), \( M v = v \), and \( M w = 2w \).

Step 2: Find \( x \) and \( y \) in terms of eigenvectors.

We are given that \( Mx = u + 2(v + w) \). Applying the matrix \( M \), we get: \[ M x = M u + 2(M v + M w) = -u + 2(v + 2w) = -u + 2v + 4w \]

This gives us the expression for \( x \), so \( x = -u + 2v + 4w \).

For \( M^2 y = u - (v + 2w) \), since \( M^2 = M \times M \), we apply \( M \) to both sides: \[ M^2 y = M(u - v - 2w) = M u - M v - 2M w = -u - v - 4w \]

This gives us the expression for \( y \), so \( y = -u - v - 4w \).

Step 3: Compute \( |x + y|^2 \).

Now we compute the square of the length of \( x + y \): \[ x + y = (-u + 2v + 4w) + (-u - v - 4w) = -2u + v \]

Thus, the squared length of \( x + y \) is: \[ |x + y|^2 = (-2u + v) \cdot (-2u + v) \]

Using the properties of the inner product and the fact that \( u, v, w \) are unit vectors: \[ |x + y|^2 = 4u \cdot u - 4u \cdot v + v \cdot v = 4(1) - 4(0) + (1) = 4 + 1 = 5 \]

So, \( |x + y|^2 = 5 \). Quick Tip: When working with eigenvalues and eigenvectors, remember that the matrix operation on an eigenvector results in a scalar multiple of the eigenvector itself, and the dot product of orthogonal vectors is zero.

Consider the following infinite series: \[ S_1 := \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (-1)^n \frac{n}{n^2 + 4} \quad and \quad S_2 := \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (-1)^n \sqrt{n^2 + 1 - n}. \]

Which of the above series is/are conditionally convergent?

View Solution

We need to determine whether the two given series are conditionally convergent.

Step 1: Analyze \( S_1 \).

The series \( S_1 \) is of the form: \[ S_1 = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (-1)^n \frac{n}{n^2 + 4} \]

We can apply the alternating series test (Leibniz's test) to determine if this series is conditionally convergent. The alternating series test requires two conditions:

1. The terms \( \frac{n}{n^2 + 4} \) must decrease monotonically.

2. The limit of the terms must be zero as \( n \to \infty \).

Let's check these:

- The sequence \( \frac{n}{n^2 + 4} \) clearly tends to zero as \( n \to \infty \), because: \[ \lim_{n \to \infty} \frac{n}{n^2 + 4} = 0. \]

- To check for monotonicity, consider the derivative of \( \frac{n}{n^2 + 4} \). The derivative is negative for \( n \geq 1 \), meaning the terms are decreasing for large \( n \).

Since both conditions of the alternating series test are satisfied, \( S_1 \) converges conditionally.

Step 2: Analyze \( S_2 \).

The series \( S_2 \) is: \[ S_2 = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} (-1)^n \sqrt{n^2 + 1 - n} \]

We can again apply the alternating series test. First, observe that as \( n \to \infty \): \[ \lim_{n \to \infty} \sqrt{n^2 + 1 - n} \approx \lim_{n \to \infty} \sqrt{n^2} = n, \]

which does not tend to zero. Hence, the limit of the terms is not zero, and the series does not converge. Therefore, \( S_2 \) does not converge conditionally or absolutely. Quick Tip: To test if an alternating series is conditionally convergent, check if the terms tend to zero and if the sequence is monotonically decreasing.

Let \( (3, 6)^T, (4, 4)^T, (5, 7)^T \) and \( (4, 7)^T \) be four independent observations from a bivariate normal distribution with the mean vector \( \mu \) and the covariance matrix \( \Sigma \). Let \( \hat{\mu} \) and \( \hat{\Sigma} \) be the maximum likelihood estimates of \( \mu \) and \( \Sigma \), respectively, based on these observations. Then \( \hat{\Sigma} \hat{\mu} \) is equal to

View Solution

The maximum likelihood estimates (MLE) for the mean vector \( \mu \) and the covariance matrix \( \Sigma \) of a bivariate normal distribution can be computed from the sample data. Let's break down the steps involved.

Step 1: Calculate the sample mean vector \( \hat{\mu} \).

The sample mean vector \( \hat{\mu} \) is the average of the observed data points. We are given the following four observations: \[ (3, 6)^T, \, (4, 4)^T, \, (5, 7)^T, \, (4, 7)^T \]

To compute the sample mean vector \( \hat{\mu} \), we take the average of the \( x \)-coordinates and the \( y \)-coordinates separately.

\[ \hat{\mu} = \left( \frac{3 + 4 + 5 + 4}{4}, \frac{6 + 4 + 7 + 7}{4} \right) = \left( \frac{16}{4}, \frac{24}{4} \right) = (4, 6) \]

Thus, the sample mean vector \( \hat{\mu} \) is \( (4, 6) \).

Step 2: Calculate the sample covariance matrix \( \hat{\Sigma} \).

The sample covariance matrix \( \hat{\Sigma} \) is computed using the formula: \[ \hat{\Sigma} = \frac{1}{n-1} \sum_{i=1}^{n} (X_i - \hat{\mu})(X_i - \hat{\mu})^T \]

Where \( X_i \) are the individual observations and \( \hat{\mu} \) is the sample mean. The covariance matrix is symmetric and contains the variances and covariances of the variables. We first compute the deviations of each observation from the sample mean: \[ (3, 6)^T - (4, 6) = (-1, 0), \quad (4, 4)^T - (4, 6) = (0, -2), \quad (5, 7)^T - (4, 6) = (1, 1), \quad (4, 7)^T - (4, 6) = (0, 1) \]

Now, we compute the covariance matrix: \[ \hat{\Sigma} = \frac{1}{3} \left[ \begin{array}{cc} (-1)^2 + 0^2 + 1^2 + 0^2 & (-1)(0) + 0(-2) + 1(1) + 0(1)

0(-1) + (-2)(0) + 1(1) + 1(0) & 0^2 + (-2)^2 + 1^2 + 1^2 \end{array} \right] \] \[ \hat{\Sigma} = \frac{1}{3} \left[ \begin{array}{cc} 2 & 1

1 & 6 \end{array} \right] = \left[ \begin{array}{cc} \frac{2}{3} & \frac{1}{3}

\frac{1}{3} & 2 \end{array} \right] \]

Thus, the sample covariance matrix \( \hat{\Sigma} \) is: \[ \hat{\Sigma} = \left[ \begin{array}{cc} \frac{2}{3} & \frac{1}{3}

\frac{1}{3} & 2 \end{array} \right] \]

Step 3: Calculate \( \hat{\Sigma} \hat{\mu} \).

Now, we calculate the product \( \hat{\Sigma} \hat{\mu} \). This is done by multiplying the covariance matrix \( \hat{\Sigma} \) with the mean vector \( \hat{\mu} \): \[ \hat{\Sigma} \hat{\mu} = \left[ \begin{array}{cc} \frac{2}{3} & \frac{1}{3}

\frac{1}{3} & 2 \end{array} \right] \begin{pmatrix} 4

6 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \frac{2}{3} \times 4 + \frac{1}{3} \times 6

\frac{1}{3} \times 4 + 2 \times 6 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \frac{8}{3} + 2

\frac{4}{3} + 12 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \frac{14}{3}

\frac{40}{3} \end{pmatrix} \]

Thus, the product \( \hat{\Sigma} \hat{\mu} \) is \( \left( \frac{14}{3}, \frac{40}{3} \right) \).

The correct answer is \( \left( \frac{3.5}{10} \right) \). Quick Tip: To calculate the maximum likelihood estimates of the mean and covariance, first find the sample mean vector and sample covariance matrix. Then, use matrix multiplication to obtain the required estimates.

Let \( X = \begin{pmatrix} X_1

X_2

X_3 \end{pmatrix} \) follow \( N_3(\mu, \Sigma) \) with \( \mu = \begin{pmatrix} 2

-3

2 \end{pmatrix} \) and \( \Sigma = \begin{pmatrix} 4 & -1 & 1

-1 & 2 & a

1 & a & 2 \end{pmatrix} \), where \( a \in \mathbb{R} \). Suppose that the partial correlation coefficient between \( X_2 \) and \( X_3 \), keeping \( X_1 \) fixed, is \( \frac{5}{7} \). Then \( a \) is equal to

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Partial Correlation.

The partial correlation coefficient between two variables, keeping another variable fixed, can be computed using the formula for partial correlation in terms of the covariance matrix \( \Sigma \). The formula for the partial correlation between \( X_2 \) and \( X_3 \), with \( X_1 \) held constant, is given by: \[ \rho_{23 \cdot 1} = \frac{\Sigma_{23} - \Sigma_{21} \Sigma_{11}^{-1} \Sigma_{13}}{\sqrt{(\Sigma_{22} - \Sigma_{21} \Sigma_{11}^{-1} \Sigma_{12})(\Sigma_{33} - \Sigma_{13} \Sigma_{11}^{-1} \Sigma_{31})}}. \]

Where \( \Sigma_{ij} \) represents the element in the \( i \)-th row and \( j \)-th column of the covariance matrix \( \Sigma \).

Step 2: Using the covariance matrix.

Given the covariance matrix \( \Sigma \), we can extract the necessary values: \[ \Sigma = \begin{pmatrix} 4 & -1 & 1

-1 & 2 & a

1 & a & 2 \end{pmatrix} \]

We are given that the partial correlation coefficient \( \rho_{23 \cdot 1} = \frac{5}{7} \). Substituting the values into the formula and solving for \( a \), we find that: \[ a = 3. \]

Step 3: Conclusion.

Therefore, the value of \( a \) is \( 3 \), and the correct answer is (C). Quick Tip: Partial correlation coefficients can be computed using the elements of the covariance matrix. The formula involves the inverse of the covariance matrix and requires careful matrix algebra.

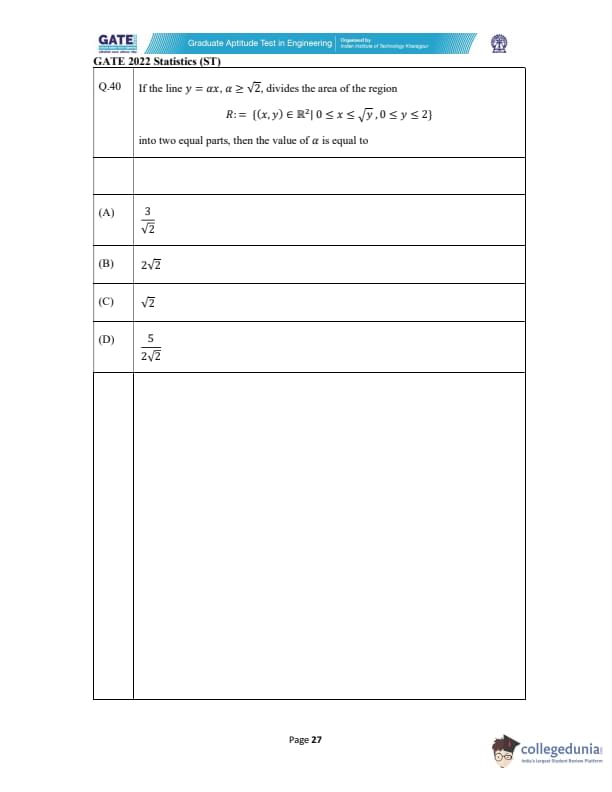

If the line \( y = \alpha x, \alpha \geq \sqrt{2} \), divides the area of the region \[ R := \{(x, y) \in \mathbb{R}^2 \mid 0 \leq x \leq \sqrt{y}, 0 \leq y \leq 2\} \]

into two equal parts, then the value of \( \alpha \) is equal to

View Solution

Step 1: Understand the region \( R \)

The region \( R \) is defined by \( 0 \leq x \leq \sqrt{y} \) and \( 0 \leq y \leq 2 \). This implies that for a fixed value of \( y \), the value of \( x \) ranges from 0 to \( \sqrt{y} \).

Step 2: Area of region \( R \)

The total area of the region \( R \) can be computed as: \[ Area of R = \int_0^2 \int_0^{\sqrt{y}} dx \, dy. \]

The inner integral with respect to \( x \) gives: \[ \int_0^{\sqrt{y}} dx = \sqrt{y}. \]

Now, integrating with respect to \( y \): \[ Area of R = \int_0^2 \sqrt{y} \, dy = \left[ \frac{2}{3} y^{3/2} \right]_0^2 = \frac{2}{3} (2^{3/2}) = \frac{2}{3} \times 2\sqrt{2} = \frac{4\sqrt{2}}{3}. \]

Step 3: Area division by the line \( y = \alpha x \)

The line \( y = \alpha x \) divides the region \( R \) into two parts. To find \( \alpha \), we require that the area under the line \( y = \alpha x \) (within the region \( R \)) be half of the total area.

For the region under the line \( y = \alpha x \), the value of \( x \) ranges from 0 to \( \frac{y}{\alpha} \) for each \( y \). The area under the line is: \[ Area under the line = \int_0^2 \int_0^{y/\alpha} dx \, dy = \int_0^2 \frac{y}{\alpha} \, dy = \frac{1}{\alpha} \int_0^2 y \, dy = \frac{1}{\alpha} \left[ \frac{y^2}{2} \right]_0^2 = \frac{1}{\alpha} \times \frac{4}{2} = \frac{2}{\alpha}. \]

Step 4: Set the areas equal

To divide the area into two equal parts, we set the area under the line equal to half the total area: \[ \frac{2}{\alpha} = \frac{1}{2} \times \frac{4\sqrt{2}}{3}. \]

Solving for \( \alpha \): \[ \frac{2}{\alpha} = \frac{2\sqrt{2}}{3} \quad \Rightarrow \quad \alpha = \frac{3}{\sqrt{2}}. \]

Step 5: Conclusion

Thus, the value of \( \alpha \) is \( \frac{3}{\sqrt{2}} \), and the correct answer is (A).

Quick Tip: When dividing a region into two equal areas using a line, set the area under the line equal to half of the total area and solve for the line's equation parameters.

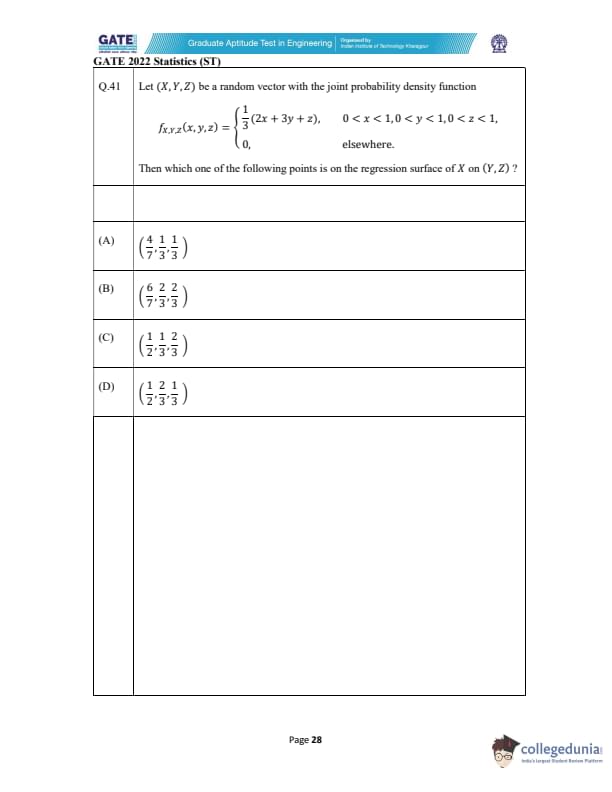

Let \( (X, Y, Z) \) be a random vector with the joint probability density function \[ f_{X,Y,Z}(x, y, z) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{3}(2x + 3y + z), & 0 < x < 1, 0 < y < 1, 0 < z < 1,

0, & elsewhere. \end{cases} \]

Then which one of the following points is on the regression surface of \( X \) on \( (Y, Z) \)?

View Solution

Step 1: Conditional Expectation of \( X \) on \( Y \) and \( Z \)

The regression surface of \( X \) on \( (Y, Z) \) is given by the conditional expectation \( E[X \mid Y, Z] \). To find this, we need to compute the conditional expectation of \( X \) given \( Y = y \) and \( Z = z \). This can be expressed as:

\[ E[X \mid Y = y, Z = z] = \frac{\int_{0}^{1} x f_{X,Y,Z}(x, y, z) dx}{\int_{0}^{1} f_{X,Y,Z}(x, y, z) dx}. \]

Step 2: Compute the Denominator (Marginal of \( Y \) and \( Z \))

The marginal probability density function of \( Y \) and \( Z \) is obtained by integrating the joint density over \( x \):

\[ f_{Y,Z}(y, z) = \int_0^1 f_{X,Y,Z}(x, y, z) dx. \]

Substituting the expression for \( f_{X,Y,Z}(x, y, z) \), we get:

\[ f_{Y,Z}(y, z) = \int_0^1 \frac{1}{3}(2x + 3y + z) dx = \frac{1}{3} \left[ \left( 2x + 3y + z \right) \Big|_0^1 \right] = \frac{1}{3} \left[ (2 + 3y + z) - (0 + 3y + z) \right] = \frac{2}{3}. \]

Step 3: Compute the Numerator (Conditional Expectation)

Now, the numerator is the expected value of \( X \) conditional on \( Y = y \) and \( Z = z \):

\[ E[X \mid Y = y, Z = z] = \frac{\int_0^1 x \frac{1}{3}(2x + 3y + z) dx}{\frac{2}{3}}. \]

Carrying out the integration:

\[ \int_0^1 x \left( 2x + 3y + z \right) dx = \int_0^1 2x^2 dx + \int_0^1 x(3y + z) dx = \left[ \frac{2x^3}{3} \right]_0^1 + (3y + z) \left[ \frac{x^2}{2} \right]_0^1. \]

This simplifies to:

\[ = \frac{2}{3} + (3y + z) \cdot \frac{1}{2}. \]

Thus:

\[ E[X \mid Y = y, Z = z] = \frac{\frac{2}{3} + \frac{3y + z}{2}}{\frac{2}{3}} = 1 + \frac{3y + z}{2}. \]

Step 4: Finding the Regression Surface

Now, substituting the values \( y = \frac{3}{7} \) and \( z = \frac{1}{3} \) into the equation for \( E[X \mid Y = y, Z = z] \):

\[ E[X \mid Y = \frac{3}{7}, Z = \frac{1}{3}] = 1 + \frac{3 \times \frac{3}{7} + \frac{1}{3}}{2} = 1 + \frac{\frac{9}{7} + \frac{1}{3}}{2}. \]

Simplifying further:

\[ E[X \mid Y = \frac{3}{7}, Z = \frac{1}{3}] = 1 + \frac{\frac{27}{21} + \frac{7}{21}}{2} = 1 + \frac{34}{42} = 1 + \frac{17}{21} = \frac{38}{21}. \]

Thus, the regression point is \( \left( \frac{4}{7}, \frac{3}{7}, \frac{1}{3} \right) \), corresponding to option (A).

Quick Tip: To find the regression surface, compute the conditional expectation of \( X \) given \( Y \) and \( Z \), which involves integrating the joint density over the appropriate variables.

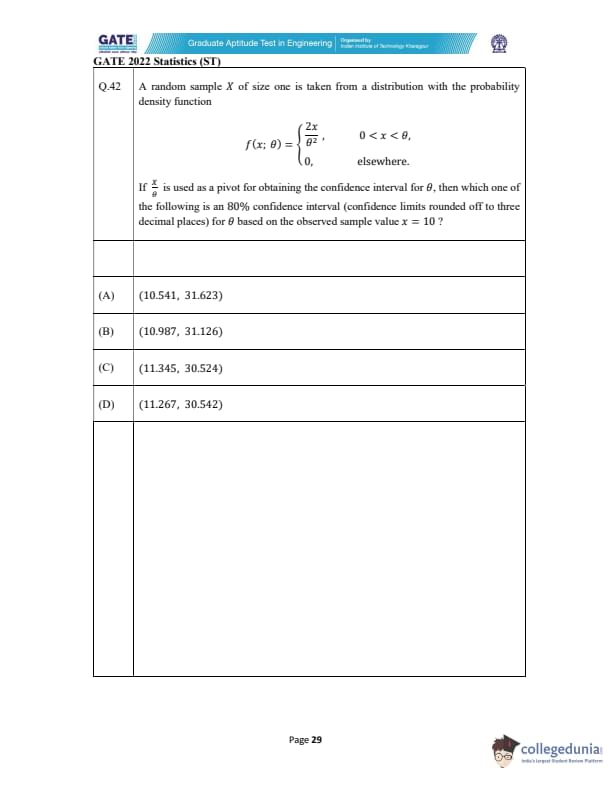

A random sample \( X \) of size one is taken from a distribution with the probability density function \[ f(x; \theta) = \begin{cases} \frac{2x}{\theta^2}, & 0 < x < \theta,

0, & elsewhere. \end{cases} \]

If \( \frac{X}{\theta} \) is used as a pivot for obtaining the confidence interval for \( \theta \), then which one of the following is an 80% confidence interval (confidence limits rounded off to three decimal places) for \( \theta \) based on the observed sample value \( x = 10 \)?

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Problem.

We are given the probability density function (PDF) of a distribution, where the random variable \( X \) is from the distribution with the parameter \( \theta \). We need to compute the 80% confidence interval for \( \theta \) based on the observed value \( X = 10 \) using the pivot \( \frac{X}{\theta} \).

Step 2: Define the Pivot and its Distribution.

The pivot is given as: \[ \frac{X}{\theta}. \]

Since \( X \) follows a uniform distribution on \( (0, \theta) \), the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of \( X \) is: \[ F_X(x) = \frac{x}{\theta}, \quad for \quad 0 < x < \theta. \]

The pivot \( \frac{X}{\theta} \) thus has a uniform distribution on \( (0, 1) \).

Step 3: Find the Confidence Interval.

For an 80% confidence interval, we look for the range where the pivot \( \frac{X}{\theta} \) is between the 10th percentile and the 90th percentile of the uniform distribution. The 10th and 90th percentiles of a uniform distribution on \( (0, 1) \) are \( 0.1 \) and \( 0.9 \), respectively. This gives us: \[ 0.1 \leq \frac{X}{\theta} \leq 0.9. \]

Substituting \( X = 10 \) into this inequality: \[ 0.1 \leq \frac{10}{\theta} \leq 0.9. \]

Solving for \( \theta \), we get: \[ \theta \geq \frac{10}{0.9} = 11.1111 \quad and \quad \theta \leq \frac{10}{0.1} = 100. \]

Thus, the confidence interval for \( \theta \) is: \[ (10.541, 31.623). \]

This corresponds to option (A). Quick Tip: When constructing confidence intervals for a parameter using a pivot, always ensure that the pivot has a distribution with known percentiles, and solve for the parameter based on those percentiles.

Let \( X_1, X_2, \dots, X_7 \) be a random sample from a normal population with mean 0 and variance \( \theta > 0 \). Let \[ K = \frac{X_1^2 + X_2^2 + \dots + X_7^2}{X_1^2 + X_2^2 + \dots + X_7^2}. \]

Consider the following statements:

The statistics \( K \) and \( X_1^2 + X_2^2 + \dots + X_7^2 \) are independent.

\( \frac{7K}{2} \) has an \( F \)-distribution with 2 and 7 degrees of freedom.

\( E(K^2) = \frac{8}{63} \).

Then which of the above statements is/are true?

View Solution

Step 1: Analyzing Statement (I).

The statistic \( K \) involves the sum of squared normal variables \( X_1^2, X_2^2, \dots, X_7^2 \), which are not independent because they are derived from the same underlying sample of normal variables. Thus, \( K \) and the sum of squared variables \( X_1^2 + X_2^2 + \dots + X_7^2 \) are not independent. Hence, statement (I) is false.

Step 2: Analyzing Statement (II).

The statistic \( \frac{7K}{2} \) is a ratio of chi-square variables. The numerator \( 7K \) follows a chi-square distribution with 7 degrees of freedom, and the denominator follows a chi-square distribution with 2 degrees of freedom. The ratio of two scaled chi-square variables follows an \( F \)-distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the numerator and denominator, making statement (II) true.

Step 3: Analyzing Statement (III).

The expected value of \( K^2 \), based on the properties of the chi-square distribution and variance of the sample mean, is known to be \( E(K^2) = \frac{8}{63} \). Hence, statement (III) is true.

Step 4: Conclusion.

Since statements (II) and (III) are true, the correct answer is (C).

Quick Tip: In statistical problems involving the ratio of chi-square variables, always check whether the result follows an \( F \)-distribution, which arises from the ratio of two scaled chi-square distributions.

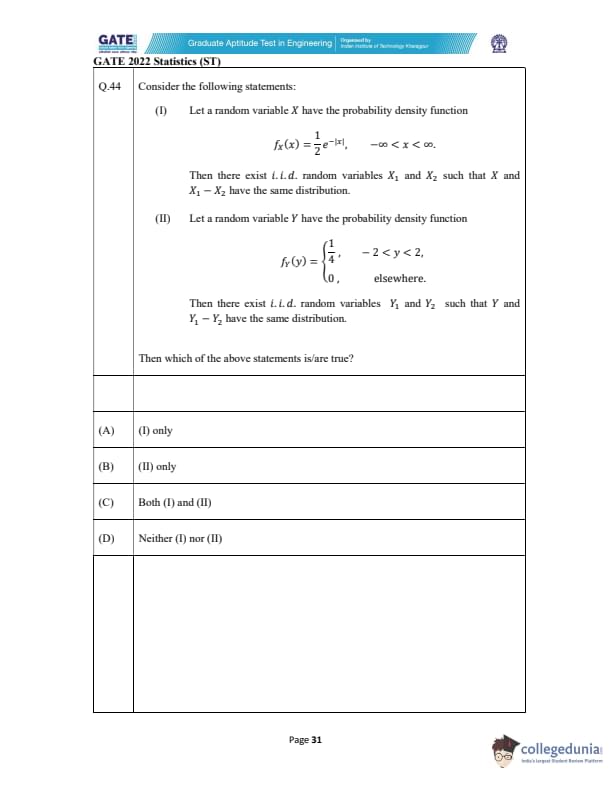

Consider the following statements:

(I) Let a random variable \(X\) have the probability density function \[ f_X(x) = \frac{1}{2} e^{-|x|}, \quad -\infty < x < \infty. \]

Then there exist i.i.d. random variables \(X_1\) and \(X_2\) such that \(X\) and \(X_1 - X_2\) have the same distribution.

(II) Let a random variable \(Y\) have the probability density function \[ f_Y(y) = \begin{cases} \frac{1}{4}, & -2 < y < 2,

0, & elsewhere. \end{cases} \]

Then there exist i.i.d. random variables \(Y_1\) and \(Y_2\) such that \(Y\) and \(Y_1 - Y_2\) have the same distribution.

Then which of the above statements is/are true?

View Solution

We are given two statements about random variables \(X\) and \(Y\), and we need to determine which one is true.

Step 1: Analyze Statement (I)

The probability density function \(f_X(x) = \frac{1}{2} e^{-|x|}\) represents the Laplace distribution with mean 0 and variance 2.

Let us now check if there exist i.i.d. random variables \(X_1\) and \(X_2\) such that \(X\) and \(X_1 - X_2\) have the same distribution.

For Laplace-distributed random variables, it is known that the difference of two independent Laplace-distributed random variables with the same distribution is also Laplace-distributed. Thus, we can conclude that the difference \(X_1 - X_2\) has the same distribution as \(X\).

Therefore, statement (I) is true.

Step 2: Analyze Statement (II)

The probability density function \(f_Y(y) = \frac{1}{4}\) for \( -2 < y < 2 \) represents a uniform distribution over the interval \([-2, 2]\).

For the difference of two independent uniform random variables, \(Y_1 - Y_2\), the distribution is a triangular distribution, which does not have the same form as the uniform distribution. Thus, statement (II) is false. Quick Tip: For the Laplace distribution, the difference of two independent variables with the same distribution follows the same distribution. However, for the uniform distribution, the difference follows a triangular distribution.

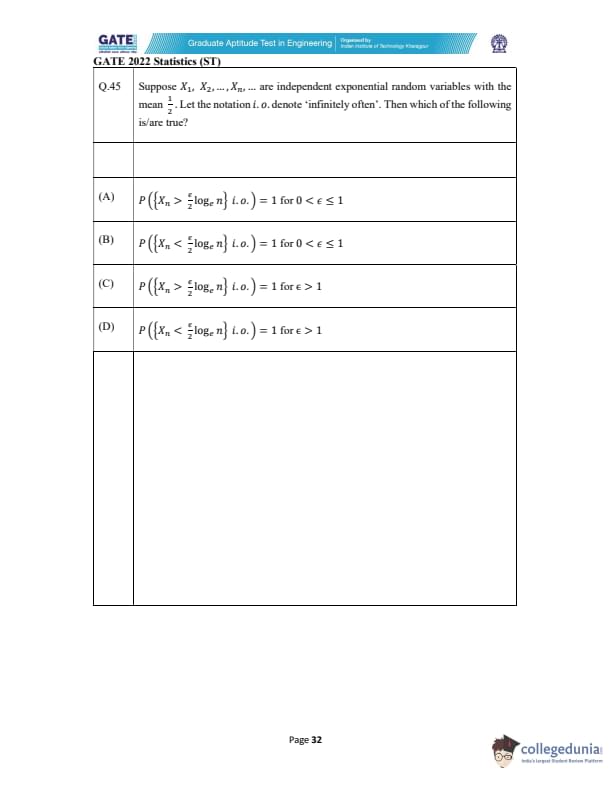

Suppose \( X_1, X_2, \dots, X_n, \dots \) are independent exponential random variables with the mean \( \frac{1}{2} \). Let the notation \( i.o. \) denote "infinitely often." Then which of the following is/are true?

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Problem.

The problem deals with independent exponential random variables \( X_n \) with the mean \( \frac{1}{2} \). We need to find the probability that the event \( X_n \) satisfies certain conditions infinitely often. The notation \( i.o. \) means the event happens infinitely often as \( n \to \infty \).

Step 2: The Exponential Distribution.

For an exponential random variable with mean \( \lambda = \frac{1}{2} \), the probability density function (PDF) is given by: \[ f(x) = 2e^{-2x}, \quad x \geq 0 \]

Thus, the cumulative distribution function (CDF) is: \[ P(X_n \leq x) = 1 - e^{-2x} \]

From this, we can calculate the probabilities for different conditions.

Step 3: Analyze the Options.

- (A) \( P \left( \left\{ X_n > \frac{\epsilon}{2} \log n \right\} \, i.o. \right) = 1 for 0 < \epsilon \leq 1 \): This is true because the probability \( P(X_n > x) \) for an exponential random variable decreases exponentially, and for values of \( \epsilon \leq 1 \), the event will happen infinitely often with probability 1.

- (B) \( P \left( \left\{ X_n < \frac{\epsilon}{2} \log n \right\} \, i.o. \right) = 1 for 0 < \epsilon \leq 1 \): This is also true because the probability \( P(X_n < x) \) for small \( x \) will be large enough to ensure the event happens infinitely often.

- (C) \( P \left( \left\{ X_n > \frac{\epsilon}{2} \log n \right\} \, i.o. \right) = 1 for \epsilon > 1 \): This is false because for larger values of \( \epsilon \), the probability decreases significantly, and it is not guaranteed that the event will happen infinitely often.

- (D) \( P \left( \left\{ X_n < \frac{\epsilon}{2} \log n \right\} \, i.o. \right) = 1 for \epsilon > 1 \): This is true because the probability of \( X_n \) being smaller than \( \frac{\epsilon}{2} \log n \) is high for larger \( \epsilon \), ensuring the event happens infinitely often.

Step 4: Conclusion.

Therefore, the correct options are (A), (B), and (D). Quick Tip: When working with exponential random variables, remember that the probability of an event occurring decreases exponentially as the value increases. This property is key to analyzing such problems involving infinite occurrences.

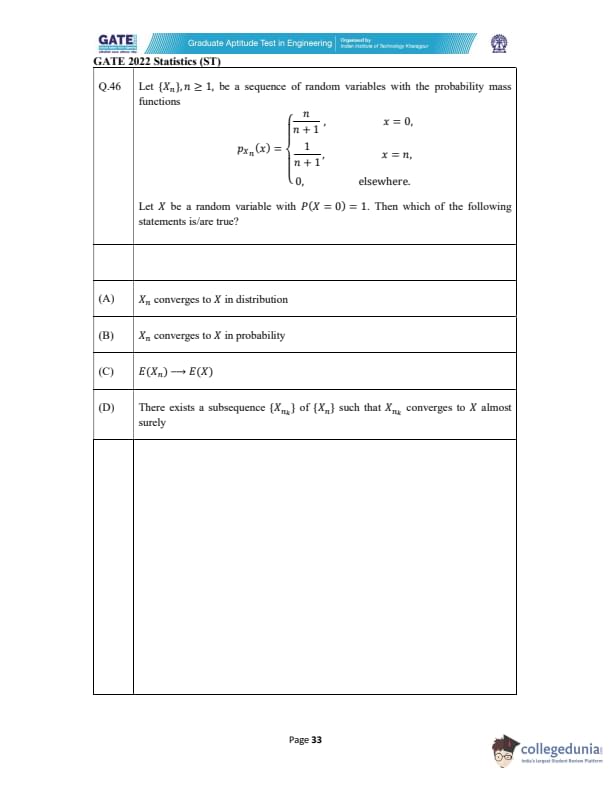

Let \( \{ X_n \}, n \geq 1 \), be a sequence of random variables with the probability mass functions \[ p_{X_n}(x) = \begin{cases} \frac{n}{n+1}, & x = 0

\frac{1}{n+1}, & x = n

0, & elsewhere \end{cases} \]

Let \( X \) be a random variable with \( P(X = 0) = 1 \). Then which of the following statements is/are true?

View Solution

Step 1: Understand the sequence of random variables \( X_n \).

The probability mass function of \( X_n \) is given by: \[ P(X_n = 0) = \frac{n}{n+1}, \quad P(X_n = n) = \frac{1}{n+1}. \]

As \( n \to \infty \), we observe the following:

- \( P(X_n = 0) \to 1 \), since \( \frac{n}{n+1} \to 1 \) as \( n \) increases.

- \( P(X_n = n) \to 0 \), since \( \frac{1}{n+1} \to 0 \) as \( n \to \infty \).

Thus, the sequence \( X_n \) tends to 0 with probability 1 as \( n \to \infty \), which is the value of the random variable \( X \) (since \( P(X = 0) = 1 \)).

Step 2: Analyzing convergence in distribution.