CBSE Class 12 Physics Question Paper 2024 PDF (Set 1- 55/4/1) is available for download here. CBSE conducted the Physics exam on March 4, 2024 from 10:30 AM to 1:30 PM. The total marks for the theory paper are 70. The question paper contains 20% MCQ-based questions, 40% competency-based questions, and 40% short and long answer type questions.

CBSE Class 12 Physics Question Paper 2024 (Set 1- 55/4/1) with Answer Key

| CBSE Class 12 2024 Physics Question Paper with Answer Key | Check Solution |

CBSE Class 12 2024 Physics Questions with Solutions

Question 1:

Two charges \(+q\) each are kept \(2a\) distance apart. A third charge \(-2q\) is placed midway between them. The potential energy of the system is:

View Solution

Calculation of Potential Energy:

Potential energy between the two \(+q\) charges:

\(\)U_1 = \frac{1{4\pi\epsilon_0 \frac{q \cdot q{2a = \frac{q^2{8\pi\epsilon_0 a\(\)

Potential energy between the first \(+q\) charge and the \(-2q\) charge:

\(\)U_2 = \frac{1{4\pi\epsilon_0 \frac{q \cdot (-2q){a = -\frac{2q^2{4\pi\epsilon_0 a = -\frac{4q^2{8\pi\epsilon_0 a\(\)

Potential energy between the second \(+q\) charge and the \(-2q\) charge:

\(\)U_3 = \frac{1{4\pi\epsilon_0 \frac{q \cdot (-2q){a = -\frac{2q^2{4\pi\epsilon_0 a = -\frac{4q^2{8\pi\epsilon_0 a\(\)

The total potential energy \(U\) is the sum of \(U_1\), \(U_2\), and \(U_3\):

\(\)U = U_1 + U_2 + U_3\(\) \(\)U = \frac{q^2{8\pi\epsilon_0 a - \frac{4q^2{8\pi\epsilon_0 a - \frac{4q^2{8\pi\epsilon_0 a\(\) \(\)U = \frac{(1 - 4 - 4)q^2{8\pi\epsilon_0 a\(\) \(\)U = -\frac{7q^2{8\pi\epsilon_0 a\(\)

Therefore, the potential energy of the system is \(-\frac{7q^2}{8\pi\epsilon_0 a}\). Quick Tip: Potential energy in an electrostatic system depends on charge magnitudes and their separations. Attractive interactions result in negative energy, while repulsive interactions contribute positively.

Two identical small conducting balls \( B_1 \) and \( B_2 \) are given \(-7\) \(\mu C\) and \(+4\) \(\mu C\) charges respectively. They are brought in contact with a third identical ball \( B_3 \) and then separated. If the final charge on each ball is \(-2\) \(\mu C\), the initial charge on \( B_3 \) was:

View Solution

Charge Redistribution Calculation:

- The total charge on the three balls before contact is:

\[ Q_{total} = Q_1 + Q_2 + Q_3 \]

- After bringing them in contact, the charge distributes equally among them:

\[ Q_{final} = \frac{Q_{total}}{3} = -2 pC \]

- Given, \( Q_1 = -7 pC \), \( Q_2 = +4 pC \), and \( Q_3 \) is unknown:

\[ \frac{-7 + 4 + Q_3}{3} = -2 \]

\[ -3 + Q_3 = -6 \]

\[ Q_3 = -3 pC \]

Thus, the initial charge on \( B_3 \) was \(-3\) pC.

Quick Tip: In charge redistribution problems, when identical conductors are connected, the final charge on each is the arithmetic mean of the total charge.

The quantum nature of light explains the observations on the photoelectric effect as:

View Solution

Explanation of the Photoelectric Effect:

- According to Einstein’s photoelectric equation:

\[ K_{max} = h f - \phi \]

where \( h \) is Planck’s constant, \( f \) is the frequency of incident light, and \( \phi \) is the work function of the material.

- The photoelectric effect demonstrates that:

- If the frequency \( f \) of the incident light is less than a threshold frequency \( f_0 \), no electrons are emitted.

- Increasing the frequency above \( f_0 \) increases the kinetic energy of emitted electrons.

- The intensity of light affects the number of electrons emitted, but not their kinetic energy.

Thus, the correct explanation for the quantum nature of light in the photoelectric effect is that there exists a minimum threshold frequency below which no electrons are emitted.

Quick Tip: The photoelectric effect provided crucial evidence for the particle nature of light, leading to the development of quantum mechanics.

The radius \( r_n \) of the \( n^{th} \) orbit in the Bohr model of the hydrogen atom varies with \( n \) as:

View Solution

Bohr’s Model and Orbital Radius:

- According to Bohr’s atomic model, the radius of the \( n^{th} \) orbit is given by:

\[ r_n = \frac{n^2 h^2 \epsilon_0}{\pi m e^2} \]

- From the above equation, we observe that \( r_n \propto n^2 \), meaning the orbital radius increases as the square of the principal quantum number \( n \).

- This is a fundamental result derived from the quantization of angular momentum in the Bohr model.

Thus, the radius of the \( n^{th} \) orbit varies as \( n^2 \), making the correct answer \( r_n \propto n^2 \).

Quick Tip: In hydrogen-like atoms, the energy levels and orbital radii are quantized, following \( r_n \propto n^2 \) and \( E_n \propto -\frac{1}{n^2} \).

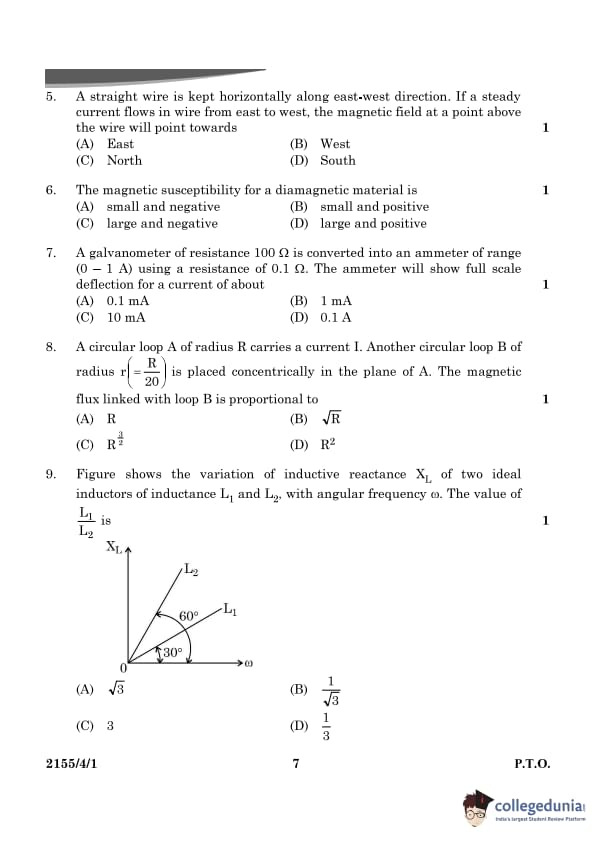

A straight wire is kept horizontally along the east-west direction. If a steady current flows in the wire from east to west, the magnetic field at a point above the wire will point towards:

View Solution

Application of Right-Hand Thumb Rule:

- The magnetic field due to a current-carrying wire follows the right-hand thumb rule:

- Point the thumb in the direction of current (east to west).

- The curled fingers indicate the direction of the magnetic field around the wire.

- At a point above the wire, the magnetic field is directed towards the north.

Thus, the correct answer is North.

Quick Tip: Use the right-hand thumb rule to determine the direction of the magnetic field around a current-carrying wire.

The magnetic susceptibility for a diamagnetic material is:

View Solution

Explanation of Diamagnetism:

- Diamagnetic materials exhibit a weak repulsion to external magnetic fields.

- Magnetic susceptibility (\( \chi \)) for diamagnetic substances is small and negative (\( \chi < 0 \)).

- This means they develop an induced magnetic field in the opposite direction of the applied field.

Thus, the correct answer is Small and negative.

Quick Tip: Diamagnetic materials like copper and bismuth are repelled by magnetic fields due to negative susceptibility.

A galvanometer of resistance 100 \( \Omega \) is converted into an ammeter of range (0 – 1 A) using a resistance of 0.1 \( \Omega \). The ammeter will show full-scale deflection for a current of about:

View Solution

Conversion of a Galvanometer to an Ammeter:

- The full-scale deflection current of the galvanometer (\( I_g \)) is given by:

\[ I_g = \frac{I}{1 + \frac{R_g}{R_s}} \]

where \( I \) is the total current, \( R_g = 100 \Omega \) is the galvanometer resistance, and \( R_s = 0.1 \Omega \) is the shunt resistance.

- Given that the ammeter range is 1 A, we solve for \( I_g \):

\[ I_g = \frac{1}{1 + \frac{100}{0.1}} = \frac{1}{1 + 1000} = \frac{1}{1001} \]

\[ I_g \approx 1 mA \]

Thus, the correct answer is 1 mA.

Quick Tip: A shunt resistance is used to convert a galvanometer into an ammeter, ensuring that most of the current bypasses the sensitive galvanometer coil.

A circular loop A of radius \( R \) carries a current \( I \). Another circular loop B of radius \( r = \frac{R}{20} \) is placed concentrically in the plane of A. The magnetic flux linked with loop B is proportional to:

View Solution

Magnetic Flux Linked with Loop B

Step 1: Magnetic Field Due to Loop A

- The magnetic field \( B \) at the center of a circular loop carrying a current \( I \) is given by the formula:

\[ B = \frac{\mu_0 I}{2R} \]

where:

- \( R \) = radius of loop A,

- \( \mu_0 \) = permeability of free space.

Step 2: Magnetic Flux Linked with Loop B

- The magnetic flux \( \Phi_B \) linked with loop B is given by:

\[ \Phi_B = B \times A_B \]

where:

- \( A_B = \pi r^2 \) is the area of loop B,

- \( r = \frac{R}{20} \) is the radius of loop B.

Thus,

\[ \Phi_B = \left( \frac{\mu_0 I}{2R} \right) \times \pi \left( \frac{R}{20} \right)^2 \]

Simplifying:

\[ \Phi_B = \frac{\mu_0 I \pi R^2}{2R \times 400} = \frac{\mu_0 I \pi R}{800} \]

Thus, the magnetic flux linked with loop B is directly proportional to \( R \).

Step 3: Conclusion

The magnetic flux linked with loop B is proportional to \( R \), so the correct answer is:

\[ \boxed{(A) \, R} \] Quick Tip: In the case of two concentric loops, the magnetic flux linked with the smaller loop is proportional to the radius of the larger loop.

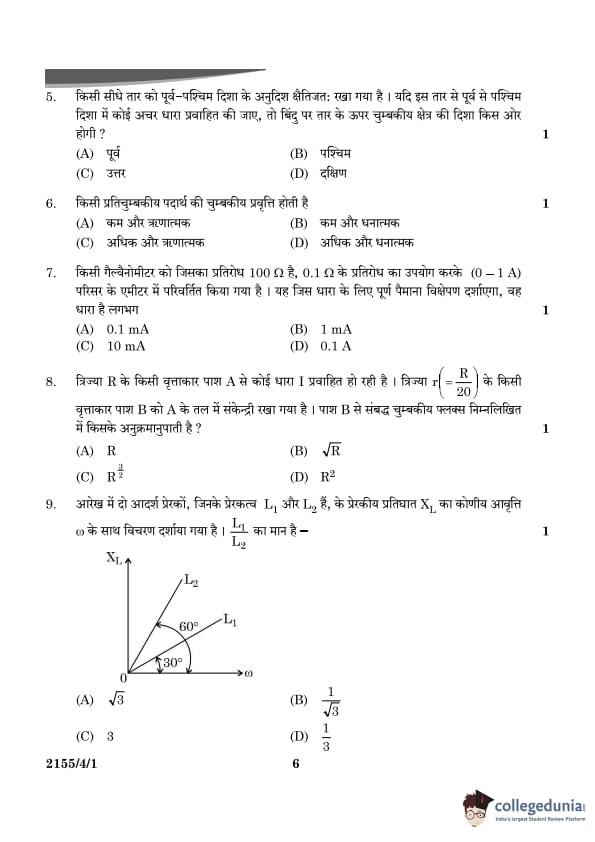

Figure shows the variation of inductive reactance \( X_L \) of two ideal inductors of inductance \( L_1 \) and \( L_2 \) with angular frequency \( \omega \). The value of \( \frac{L_1}{L_2} \) is:

View Solution

Relationship Between Inductance and Reactance:

- The inductive reactance is given by the formula:

\[ X_L = \omega L \]

- The given graph shows the variation of \( X_L \) with \( \omega \) for two inductors \( L_1 \) and \( L_2 \). The angles in the graph indicate that:

\[ \tan 30^\circ = \frac{X_{L1}}{X_{L2}} \]

- From trigonometry,

\[ \tan 30^\circ = \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}} \]

- Since \( X_L \) is proportional to \( L \), we write:

\[ \frac{L_1}{L_2} = \frac{X_{L1}}{X_{L2}} = \frac{1}{3} \]

Thus, the correct answer is \( \frac{1}{3} \).

Quick Tip: Inductive reactance \( X_L = \omega L \) increases linearly with angular frequency \( \omega \). The slope of the graph provides a direct ratio of the inductances.

The phase difference between electric field \( \vec{E} \) and magnetic field \( \vec{B} \) in an electromagnetic wave propagating along the z-axis is:

View Solution

Electromagnetic Wave Propagation:

- In an electromagnetic wave, the electric field \( \vec{E} \) and the magnetic field \( \vec{B} \) oscillate perpendicular to each other and to the direction of wave propagation.

- The wave equation for the electric and magnetic fields can be written as:

\[ E = E_0 \cos(kz - \omega t) \]

\[ B = B_0 \cos(kz - \omega t) \]

- Both fields oscillate in phase, meaning they reach their maximum and minimum values simultaneously.

- Since their equations contain the same phase term \( (kz - \omega t) \), the phase difference between \( \vec{E} \) and \( \vec{B} \) is zero.

Thus, the correct answer is Zero.

Quick Tip: In an electromagnetic wave, the electric and magnetic fields are in phase, meaning they reach their peaks and troughs at the same time.

A coil of \( N \) turns is placed in a magnetic field \( \vec{B} \) such that \( \vec{B} \) is perpendicular to the plane of the coil. \( \vec{B} \) changes with time as \( B = B_0 \cos \left( \frac{2\pi t}{T} \right) \), where \( T \) is the time period. The magnitude of emf induced in the coil will be maximum at:

View Solution

N/A Quick Tip: The induced emf is maximum when the rate of change of magnetic flux is maximum, which occurs at \( t = \frac{nT}{4} \).

In the Balmer series of the hydrogen atom, as the wavelength of spectral lines decreases, they appear:

View Solution

Hydrogen Spectrum and Balmer Series:

- The spectral lines in the Balmer series correspond to electronic transitions from higher energy levels to \( n = 2 \).

- As the wavelength decreases (moving towards the ultraviolet region), the lines become more closely spaced due to decreasing energy gaps.

- The intensity of the lines also decreases due to lower transition probabilities.

Thus, the correct answer is Closer together and weaker in intensity.

Quick Tip: In spectral series, the spacing between successive lines decreases as they approach the series limit.

Assertion (A): Electrons are ejected from the surface of zinc when it is irradiated by yellow light.

Reason (R): Energy associated with a photon of yellow light is more than the work function of zinc.

View Solution

Explanation of the Photoelectric Effect:

- The work function of zinc is greater than the energy of yellow light photons, meaning yellow light cannot eject electrons.

- Since the energy of yellow light is insufficient, Reason (R) is also false.

Thus, both Assertion (A) and Reason (R) are incorrect.

Quick Tip: The photoelectric effect occurs only if the incident light frequency is above the threshold frequency of the metal.

Assertion (A): The temperature coefficient of resistance is positive for metals and negative for p-type semiconductors.

Reason (R): The charge carriers in metals are negatively charged, whereas the majority charge carriers in p-type semiconductors are positively charged.

View Solution

Temperature Dependence of Resistance:

- Metals have a positive temperature coefficient because resistance increases with temperature due to more frequent electron collisions.

- Semiconductors have a negative temperature coefficient as increasing temperature generates more charge carriers, reducing resistance.

- The nature of charge carriers does not explain this behavior.

Thus, both statements are true, but Reason (R) does not correctly explain Assertion (A).

Quick Tip: For metals, resistance increases with temperature, whereas for semiconductors, resistance decreases with temperature.

Assertion (A): When electrons drift in a conductor, it does not mean that all free electrons in the conductor are moving in the same direction.

Reason (R): The drift velocity is superposed over large random velocities of electrons.

View Solution

Explanation of Electron Drift in Conductors:

- Electrons in a conductor exhibit random motion due to thermal agitation.

- When an electric field is applied, electrons acquire a small net drift velocity, which is superposed on their random motion.

- This explains why not all electrons move in the same direction.

Thus, both Assertion (A) and Reason (R) are true, and Reason (R) correctly explains Assertion (A).

Quick Tip: Drift velocity is the small net velocity acquired by electrons in a conductor due to an applied electric field.

Assertion (A): In interference and diffraction of light, light energy reduces in one region producing a dark fringe. It increases in another region and produces a bright fringe.

Reason (R): This happens because energy is not conserved in the phenomena of interference and diffraction.

View Solution

Explanation of Interference and Diffraction:

- Energy is redistributed, not lost, in interference and diffraction, meaning Reason (R) is false.

- Bright and dark fringes are created due to constructive and destructive interference, respectively.

Thus, Assertion (A) is true, but Reason (R) is false.

Quick Tip: In interference and diffraction, energy is redistributed without being lost, preserving conservation of energy.

Draw the circuit diagram of a p-n junction diode in (i) forward biasing and (ii) reverse biasing. Also, draw its I-V characteristics in the two cases.

View Solution

Understanding p-n Junction Diode Biasing

- A p-n junction diode allows current flow in one direction (forward bias) and blocks current in the opposite direction (reverse bias).

(i) Forward Biasing:

- The p-side (anode) is connected to the positive terminal of the battery, and the n-side (cathode) is connected to the negative terminal.

- This reduces the depletion region width, allowing current to flow.

Circuit Diagram for Forward Biasing:

I-V Characteristics in Forward Bias:

- The current increases exponentially after the threshold voltage (0.7V for silicon, 0.3V for germanium).

(ii) Reverse Biasing:

- The p-side is connected to the negative terminal, and the n-side is connected to the positive terminal.

- This increases the depletion region width, preventing current flow (except for a small leakage current).

Circuit Diagram for Reverse Biasing:

I-V Characteristics in Reverse Bias:

- A small leakage current flows until the breakdown voltage is reached.

Quick Tip: In forward bias, current flows easily after the threshold voltage. In reverse bias, only a small leakage current exists until breakdown.

A proton and an \( \alpha \)-particle are accelerated through different potentials \( V_1 \) and \( V_2 \) respectively so that they have the same de Broglie wavelengths. Find \( \frac{V_1}{V_2} \).

View Solution

De Broglie Wavelength Relation:

The de Broglie wavelength is given by:

\(\lambda = \frac{h}{p}\), where \(h\) is Planck's constant and \(p\) is the momentum.

The kinetic energy (KE) is given by:

\[ KE = \frac{p^2}{2m} \implies p = \sqrt{2mKE} \]

The kinetic energy gained by a charge \(q\) accelerated through a potential \(V\) is:

\[ KE = qV \]

Since the de Broglie wavelengths are equal:

\(\lambda_p = \lambda_{\alpha}\). Therefore, \(\frac{h}{p_p} = \frac{h}{p_{\alpha}}\), which implies \(p_p = p_{\alpha}\). \[ \sqrt{2m_p KE_p} = \sqrt{2m_{\alpha} KE_{\alpha}} \]

Squaring both sides gives:

\[ 2m_p KE_p = 2m_{\alpha} KE_{\alpha} \] \[ m_p KE_p = m_{\alpha} KE_{\alpha} \]

Substituting \(KE = qV\): \[ m_p q_p V_1 = m_{\alpha} q_{\alpha} V_2 \]

We know that the mass of the alpha particle is approximately four times the mass of the proton, and the charge of the alpha particle is twice the charge of the proton:

\(m_{\alpha} \approx 4m_p\) and \(q_{\alpha} = 2q_p\). Substituting these values:

\[ m_p q_p V_1 = (4m_p)(2q_p) V_2 \] \[ m_p q_p V_1 = 8m_p q_p V_2 \]

Dividing both sides by \(m_p q_p\): \[ V_1 = 8V_2 \]

Therefore: \[ \frac{V_1}{V_2} = 8 \] Quick Tip: For particles with the same de Broglie wavelength, the accelerating voltage is proportional to the mass of the particle.

A ray of light is incident normally on one face of an equilateral glass prism of refractive index \( P \). When the prism is completely immersed in a transparent medium, it is observed that the emergent ray just grazes the adjacent face. Find the refractive index of the medium.

View Solution

Applying Snell’s Law:

- The angle of refraction at the second face of the prism is the critical angle \( C \), so:

\[ \sin C = \frac{n_{medium}}{n_{prism}} \]

- For an equilateral prism, the angle of incidence inside the prism is:

\[ r = \frac{A}{2} = \frac{60^\circ}{2} = 30^\circ \]

- The critical angle \( C \) is given by:

\[ \sin C = \frac{1}{n} \]

Since \( C = 60^\circ \):

\[ \sin 60^\circ = \frac{n_{medium}}{n_{prism}} \]

\[ \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} = \frac{n_{medium}}{n_{prism}} \]

\[ n_{medium} = \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} n_{prism} \]

Thus, the refractive index of the medium is \( \frac{\sqrt{3}}{2} n_{prism} \).

Quick Tip: The critical angle condition is used to determine the refractive index of the medium when total internal reflection occurs.

Two electric heaters have power ratings \( P_1 \) and \( P_2 \), at voltage \( V \). They are connected in series to a DC source of voltage \( V \). Find the power consumed by the combination. Will they consume the same power if connected in parallel across the same source?

View Solution

Power Consumption in Series and Parallel Connections:

(i) Power Consumption in Series:

- The resistance of each heater is:

\[ R_1 = \frac{V^2}{P_1}, \quad R_2 = \frac{V^2}{P_2} \]

- The total resistance in series is:

\[ R_{eq} = R_1 + R_2 = \frac{V^2}{P_1} + \frac{V^2}{P_2} \]

- The total current in the circuit is:

\[ I = \frac{V}{R_{eq}} \]

- The power consumed in series is:

\[ P_{series} = I^2 R_{eq} \]

\[ P_{series} = \frac{V^2}{R_{eq}} = \frac{V^2}{\frac{V^2}{P_1} + \frac{V^2}{P_2}} \]

\[ P_{series} = \frac{P_1 P_2}{P_1 + P_2} \]

(ii) Power Consumption in Parallel:

- In parallel, the power consumed by each heater remains the same as their original ratings:

\[ P_{parallel} = P_1 + P_2 \]

Thus, the heaters consume different power in series and the same power in parallel.

Quick Tip: In a series connection, the total power is given by the harmonic mean of the two power ratings. In a parallel connection, the total power is simply the sum of the individual powers.

(a) An air bubble is trapped at point B (CB = 20 cm) in a glass sphere of radius 40 cm and refractive index 1.5 as shown in the figure. Find the nature and position of the image of the bubble as seen by an observer at point P.

View Solution

Applying Refraction at Spherical Surface:

Given Information:

Radius of the glass sphere, \(R = 40 cm\).

Refractive index of the glass, \(\mu = 1.5\).

Distance of the bubble from the center of the sphere, \(CB = 20 cm\).

Therefore, the distance of the bubble from the refracting surface (point B), \(u = -20 cm\). (Negative because it's opposite the direction of incident light).

Refraction at a Spherical Surface:

The formula for refraction at a spherical surface is:

\[ \frac{\mu_2}{v} - \frac{\mu_1}{u} = \frac{\mu_2 - \mu_1}{R} \]

where:

\(\mu_1\) is the refractive index of the medium where the object is located (glass = 1.5)

\(\mu_2\) is the refractive index of the medium where the image is formed (air = 1)

\(u\) is the object distance

\(v\) is the image distance

\(R\) is the radius of curvature of the surface

Applying the Formula:

\(\mu_1 = 1.5\)

\(\mu_2 = 1\)

\(u = -20 cm\)

\(R = -40 cm\) (Negative because the center of curvature is on the same side as the incident light).

Substituting these values into the formula:

\[ \frac{1}{v} - \frac{1.5}{-20} = \frac{1 - 1.5}{-40} \]

\[ \frac{1}{v} + \frac{1.5}{20} = \frac{-0.5}{-40} \]

\[ \frac{1}{v} = \frac{0.5}{40} - \frac{1.5}{20} \]

\[ \frac{1}{v} = \frac{0.5 - 3}{40} \]

\[ \frac{1}{v} = \frac{-2.5}{40} \]

\[ v = \frac{40}{-2.5} = -16 cm \]

Interpretation:

The image distance \(v = -16 cm\). The negative sign indicates that the image is formed on the same side of the refracting surface as the object (the air bubble). Therefore:

Position: The image is located 16 cm from point B.

Nature: Since the image is formed on the same side as the object, it is a virtual image.

The image of the air bubble is virtual and is located 16 cm from point B on the same side as the bubble. Quick Tip: For refraction at a spherical surface, use the formula \( \frac{n_2}{v} - \frac{n_1}{u} = \frac{n_2 - n_1}{R} \) to locate the image position.

(b) In normal adjustment, for a refracting telescope, the distance between the objective and eyepiece lens is 1.00 m. If the magnifying power of the telescope is 19, find the focal length of the objective and the eyepiece lens.

View Solution

Applying the Telescope Magnification Formula:

- In a refracting telescope in normal adjustment, the total length of the telescope is given by:

\[ L = f_o + f_e \]

where, \( f_o \) = focal length of the objective lens, \( f_e \) = focal length of the eyepiece lens, \( L = 1.00 \) m = total length of the telescope.

- The magnifying power \( M \) of the telescope is given by:

\[ M = \frac{f_o}{f_e} \]

- Given \( M = 19 \), we get:

\[ 19 = \frac{f_o}{f_e} \]

\[ f_o = 19 f_e \]

- Substituting this into the equation \( L = f_o + f_e \):

\[ 1.00 = 19 f_e + f_e \]

\[ 1.00 = 20 f_e \]

\[ f_e = \frac{1.00}{20} = 0.05 m = 5 cm \]

\[ f_o = 19 \times 0.05 = 0.95 m = 95 cm \]

Thus, the focal length of the objective lens is 95 cm, and the focal length of the eyepiece lens is 5 cm.

Quick Tip: In a refracting telescope, the focal length of the objective lens is much greater than that of the eyepiece, and their sum gives the total length of the telescope.

(a) Differentiate between nuclear fission and fusion.

View Solution

Nuclear Fission vs. Nuclear Fusion

\[ \begin{array}{|c|c|c|} \hline \textbf{Property} & \textbf{Nuclear Fission} & \textbf{Nuclear Fusion}

\hline Definition & A nucleus splits into smaller nuclei. & Two nuclei combine to a heavier nucleus.

\hline Energy & Large amt per fission event. & Extremely large energy release.

\hline Example & \( ^{235U + n \rightarrow ^{92}Kr + ^{141}Ba + 3n + Energy \)} & \( ^2H + ^3H \rightarrow ^4He + n + \text{Energy \)}

\hline Occurrence & In nuclear reactors and atomic bombs. & In stars like the Sun.

\hline Requirement & Critical mass of fuel and a neutron. & Extremely high temperature and pressure.

\hline \end{array} \]

Thus, nuclear fission and fusion differ in process, energy release, and applications.

Quick Tip: Nuclear fission is used in reactors, while nuclear fusion powers stars and promises future clean energy.

\[ \vec{E} = (10x + 4) \hat{i} \]

where \( x \) is in meters and \( \vec{E} \) is in N/C. Calculate the amount of work done in taking a unit charge from:

(i) \( (5 m, 0) \) to \( (10 m, 0) \)

(ii) \( (5 m, 0) \) to \( (5 m, 10 m) \)

View Solution

Work Done in Moving a Unit Charge

The work done in moving a charge \( q \) in an electric field is given by:

\[ W = \int_{x_1}^{x_2} q E \, dx \]

For a unit charge (\( q = 1 \)), this simplifies to:

\[ W = \int_{x_1}^{x_2} E \, dx \]

(i) Work Done from \( (5 m, 0) \) to \( (10 m, 0) \)

Since the electric field is along the \( x \)-axis, we compute:

\[ W = \int_{5}^{10} (10x + 4) \, dx \]

\[ W = \left[ 10 \frac{x^2}{2} + 4x \right]_{5}^{10} \]

\[ W = \left( 5 \times 100 + 4 \times 10 \right) - \left( 5 \times 25 + 4 \times 5 \right) \]

\[ W = (500 + 40) - (125 + 20) \]

\[ W = 540 - 145 = 395 J \]

Thus, the work done is 395 J.

(ii) Work Done from \( (5 m, 0) \) to \( (5 m, 10 m) \)

- Since the electric field is only along the \( x \)-direction (\( E_x \)), there is no electric field component in the \( y \)-direction.

- Work is only done when moving in the direction of the field.

Since displacement in the \( x \)-direction is zero, the work done is:

\[ W = 0 \]

Thus, the work done is 0 J.

Quick Tip: Work done in an electric field depends on displacement along the field direction. No work is done if the movement is perpendicular to the field.

Draw the graph showing the variation of scattered particles detected (\( N \)) with the scattering angle (\( \theta \)) in the Geiger-Marsden experiment. Write two conclusions that you can draw from this graph. Obtain the expression for the distance of closest approach in this experiment.

View Solution

Geiger-Marsden Experiment (Rutherford Scattering)

- The experiment measured the number of alpha particles (\( N \)) scattered at different angles (\( \theta \)).

- The observed scattering pattern led to significant conclusions about atomic structure.

Graph: Variation of \( N \) with \( \theta \)

Conclusions from the Graph

1. Most alpha particles pass undeflected, meaning the atom is mostly empty space.

2. Few particles are scattered at large angles, implying a small, dense, positively charged nucleus.

Expression for Distance of Closest Approach

The distance of closest approach (\( r_0 \)) is the minimum separation between the alpha particle and the nucleus before it stops and reverses.

- At the point of closest approach, the initial kinetic energy of the alpha particle is converted into electrostatic potential energy:

\[ \frac{1}{2} m v^2 = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \frac{Z e \cdot 2e}{r_0} \]

Solving for \( r_0 \):

\[ r_0 = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \frac{2 Z e^2}{\frac{1}{2} m v^2} \]

\[ r_0 = \frac{4 \pi \epsilon_0 \cdot 2 Z e^2}{m v^2} \]

Thus, the distance of closest approach is:

\[ r_0 = \frac{2 Z e^2}{4 \pi \epsilon_0 \cdot \frac{1}{2} m v^2} \]

This represents the minimum distance between the alpha particle and the nucleus before repulsion stops its motion.

Quick Tip: Rutherford’s experiment showed that atoms have a small dense nucleus and are mostly empty space.

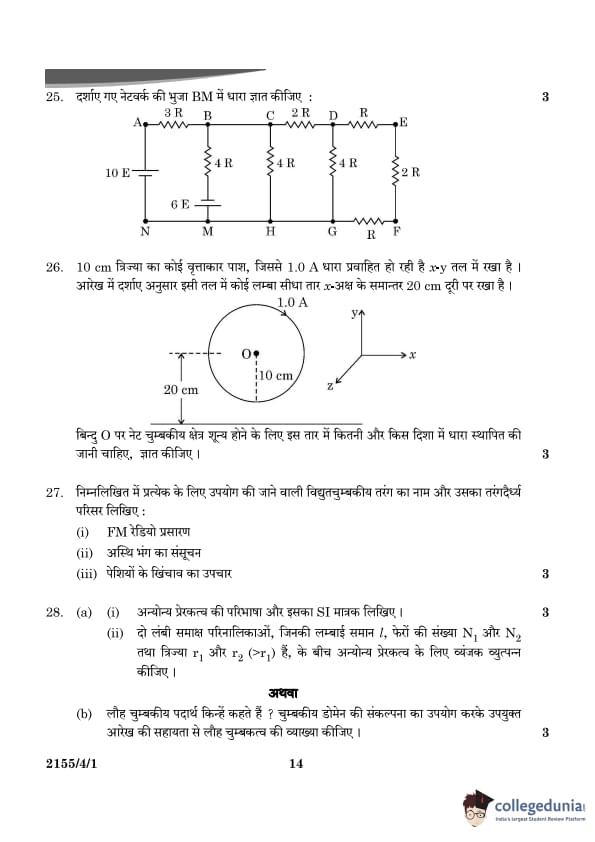

Find the current in branch BM in the network shown:

View Solution

Applying Kirchhoff’s Laws

Given that the equivalent resistance across CH is: \[ R_{CH} = 2R \]

Equivalent Circuit Diagram

The given circuit is analyzed using Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law (KVL). We apply KVL to two loops in the circuit.

Applying Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law (KVL):

In closed loop ABMNA:

Using KVL in loop ABMNA, we sum the voltage drops: \[ -3IR - 4I_1 R + 16E = 0 \]

This forms our first equation:

\begin{equation

-3IR - 4I_1 R + 16E = 0

\end{equation

In closed loop BCHMB:

Similarly, applying KVL in loop BCHMB: \[ -2R(I - I_1) - 6E + 4I_1 R = 0 \]

This forms our second equation:

\begin{equation

-2R(I - I_1) - 6E + 4I_1 R = 0

\end{equation

Solving the Equations

Now, solving equations (1) and (2) simultaneously, we obtain: \[ I_1 = \frac{25E}{13R} \]

Thus, the current \( I_1 \) in the circuit is determined. Quick Tip: Use Kirchhoff's laws to analyze complex circuits: KCL for junctions and KVL for loops.

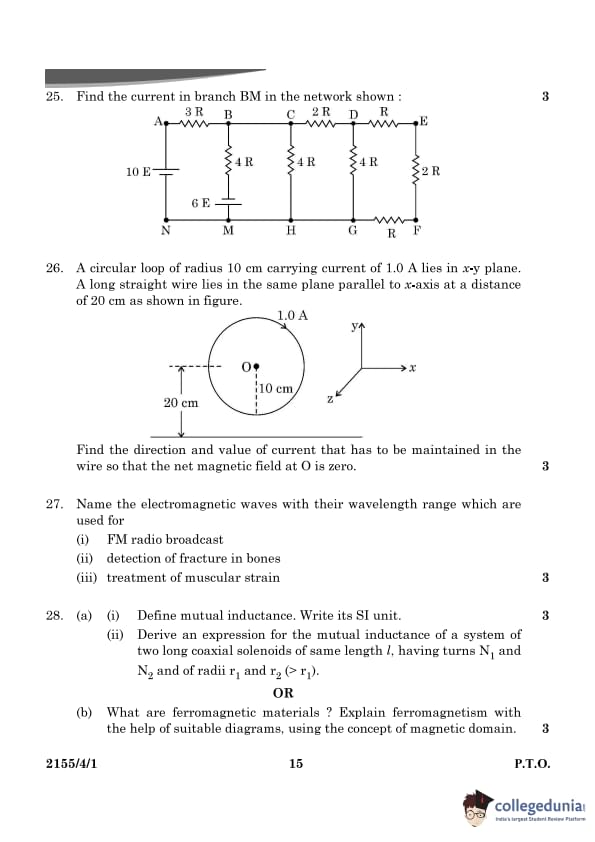

A circular loop of radius 10 cm carrying current of 1.0 A lies in the x-y plane. A long straight wire lies in the same plane parallel to the x-axis at a distance of 20 cm as shown in the figure.

Find the direction and value of current that has to be maintained in the wire so that the net magnetic field at O is zero.

View Solution

Applying Biot-Savart Law and Ampere’s Law

- The magnetic field at the center \( O \) of the circular loop is given by:

\[ B_{loop} = \frac{\mu_0 I_{loop}}{2R} \]

where \( I_{loop} = 1.0 A \), \( R = 10 \) cm = 0.1 m.

\[ B_{loop} = \frac{(4\pi \times 10^{-7}) (1)}{2 \times 0.1} \]

\[ B_{loop} = 2 \times 10^{-6} T \]

- The magnetic field due to the long straight wire at distance \( d = 20 \) cm is:

\[ B_{wire} = \frac{\mu_0 I_{wire}}{2\pi d} \]

\[ B_{wire} = \frac{(4\pi \times 10^{-7}) I_{wire}}{2\pi \times 0.2} \]

\[ B_{wire} = \frac{2 \times 10^{-7} I_{wire}}{0.2} \]

\[ B_{wire} = 10^{-6} I_{wire} \]

- For net magnetic field at \( O \) to be zero:

\[ B_{loop} = B_{wire} \]

\[ 2 \times 10^{-6} = 10^{-6} I_{wire} \]

\[ I_{wire} = 2 A \]

Direction of Current in the Wire:

- Using the Right-Hand Rule, the circular loop produces a magnetic field into the plane at O.

- To cancel it, the wire must produce a magnetic field out of the plane at O.

- This happens when current in the wire flows in the negative x-direction.

Thus, the required current in the wire is 2 A, flowing in the negative x-direction.

Quick Tip: For net zero magnetic field at a point, the contributions from different sources should cancel each other.

Name the electromagnetic waves with their wavelength range which are used for:

(i) FM radio broadcast

(ii) Detection of fracture in bones

(iii) Treatment of muscular strain

View Solution

Electromagnetic Waves and Their Applications

\[ \begin{array}{|c|c|c|} \hline \textbf{Application} & \textbf{Electromagnetic Wave} & \textbf{Wavelength Range}

\hline FM radio broadcast & Radio waves & 10 m - 1 m

\hline Detection of fracture in bones & X-rays & 10^{-11} m - 10^{-8} m

\hline Treatment of muscular strain & Infrared rays & 7.5 \times 10^{-7} m - 10^{-3} m

\hline \end{array} \]

Explanation:

- FM Radio Broadcast: Uses radio waves in the meter range, allowing transmission over long distances.

- Detection of Bone Fractures: Uses X-rays as they can penetrate soft tissues but are absorbed by bones, creating images.

- Treatment of Muscular Strain: Uses infrared rays to provide deep tissue heating and pain relief.

Quick Tip: Different electromagnetic waves have unique properties and applications based on their wavelength and energy.

(i) Define mutual inductance. Write its SI unit.

View Solution

Definition of Mutual Inductance

- Mutual inductance (\( M \)) is the property of two coils in which a change in current in one coil induces an electromotive force (emf) in the other due to electromagnetic induction.

- The induced emf in the secondary coil is given by:

\[ \mathcal{E}_2 = - M \frac{dI_1}{dt} \]

where \( I_1 \) is the current in the primary coil.

- The SI unit of mutual inductance is Henry (H), where 1 Henry = 1 Weber per Ampere (1 H = 1 Wb/A).

Quick Tip: Mutual inductance quantifies the ability of one coil to induce emf in another due to changing magnetic flux.

What are ferromagnetic materials? Explain ferromagnetism with the help of suitable diagrams, using the concept of magnetic domains.

View Solution

Understanding Ferromagnetic Materials and Ferromagnetism

Definition of Ferromagnetic Materials:

- Ferromagnetic materials are substances that exhibit strong magnetization when placed in an external magnetic field.

- These materials retain their magnetization even after the external field is removed.

- Common examples include iron (Fe), cobalt (Co), and nickel (Ni).

Explanation of Ferromagnetism:

- The phenomenon of ferromagnetism arises due to the presence of magnetic domains.

- Each domain consists of a group of atomic dipoles aligned in the same direction.

- In an unmagnetized ferromagnetic material, these domains are randomly oriented, resulting in zero net magnetization.

Magnetic Domains and Alignment:

- When an external magnetic field is applied, the domains align in the direction of the field.

- The material becomes magnetized, and the alignment of the domains increases the overall magnetic moment.

\[ B = \mu_0 (H + M) \]

where:

- \( B \) = Magnetic field in the material

- \( H \) = Applied external field

- \( M \) = Magnetization of the material

- \( \mu_0 \) = Permeability of free space

- In fully magnetized ferromagnetic materials, most domains align in the same direction, producing a strong magnetic effect.

Key Properties of Ferromagnetic Materials:

1. High Permeability: These materials have a high ability to concentrate magnetic flux.

2. Hysteresis Effect: The magnetization does not return to zero immediately after removing the field, leading to a hysteresis loop.

3. Curie Temperature (\( T_C \)): Above this temperature, the material loses its ferromagnetic properties and behaves as a paramagnet.

Conclusion:

- Ferromagnetic materials are widely used in applications like transformers, electromagnets, hard disks, and electric motors due to their ability to retain strong magnetization.

Quick Tip: Ferromagnetism arises due to domain alignment. Materials like iron, cobalt, and nickel exhibit strong magnetic properties even after the external field is removed.

Question 29.

A pure semiconductor like Ge or Si, when doped with a small amount of suitable

impurity, becomes an extrinsic semiconductor. In thermal equilibrium, the electron

and hole concentration in it are related to the concentration of intrinsic charge carriers.

A p-type or n-type semiconductor can be converted into a p-n junction by doping it

with suitable impurity. Two processes, diffusion and drift take place during formation

of a p-n junction. A semiconductor diode is basically a p-n junction with metallic

contacts provided at the ends for the application of an external voltage. A p-n junction

diode allows currents to pass only in one direction when it is forward biased. Due to

this property, a diode is widely used to rectify alternating voltages, in half-wave or full

wave configuration.

(i) When Ge is doped with a pentavalent impurity, the energy required to free the weakly bound electron from the dopant is about:

View Solution

Doping and Energy Levels in Ge

- Germanium (Ge) is a group IV element, and when doped with a pentavalent impurity (donor), extra free electrons are introduced into the conduction band.

- The energy required to free these donor electrons is very small compared to the band gap of Ge.

- In Ge, this ionization energy is approximately 0.01 eV.

Thus, the correct answer is 0.01 eV.

Quick Tip: In n-type semiconductors, donor electrons require a small energy (~0.01 eV in Ge) to jump into the conduction band.

(ii) At a given temperature, the number of intrinsic charge carriers in a semiconductor is \( 2.0 \times 10^{10} \) cm\(^{-3}\). It is doped with pentavalent impurity atoms. As a result, the number of holes in it becomes \( 8 \times 10^3 \) cm\(^{-3}\). The number of electrons in the semiconductor is:

View Solution

Carrier Concentration Calculation

- The relation between electron and hole concentrations in a semiconductor is given by:

\[ n_e \cdot n_h = n_i^2 \]

where: \( n_i = 2.0 \times 10^{10} \) cm\(^{-3} \) (intrinsic carrier concentration), \( n_h = 8 \times 10^3 \) cm\(^{-3} \) (hole concentration after doping), \( n_e \) = electron concentration after doping.

Solving for \( n_e \):

\[ n_e = \frac{n_i^2}{n_h} = \frac{(2.0 \times 10^{10})^2}{8 \times 10^3} \]

\[ n_e = \frac{4.0 \times 10^{20}}{8 \times 10^3} = 5 \times 10^{16} cm^{-3} \]

Converting to m\(^{-3}\):

\[ n_e = 5 \times 10^{22} m^{-3} \] Quick Tip: In a doped semiconductor, the product of electron and hole concentrations remains equal to \( n_i^2 \).

(iii) During the formation of a p-n junction:

View Solution

Formation of Depletion Region

- In a p-n junction, the n-region has excess electrons, and the p-region has excess holes.

- Due to the concentration difference, electrons diffuse from the n-region to the p-region.

- Similarly, holes diffuse from the p-region to the n-region.

- This diffusion leads to the formation of a depletion region, preventing further diffusion.

Thus, the correct answer is Electrons diffuse from n-region into p-region and holes diffuse from p-region into n-region.

Quick Tip: A p-n junction forms due to the diffusion of electrons from the n-side and holes from the p-side, leading to a depletion region.

(iii) Initially, during the formation of a p-n junction:

View Solution

Understanding Current Flow in p-n Junction Formation

- In a newly formed p-n junction, a concentration gradient exists between the p-region and n-region.

- This causes majority charge carriers (electrons from n-region and holes from p-region) to diffuse across the junction, leading to a large diffusion current.

- As electrons and holes diffuse, a depletion region forms, creating an internal electric field.

- This electric field generates a small drift current by moving minority carriers in the opposite direction.

- Over time, the diffusion current and drift current balance each other at equilibrium.

Thus, during the initial formation of the p-n junction, the diffusion current is large, and the drift current is small.

Quick Tip: In a p-n junction, diffusion current dominates initially, but as the depletion region builds up, drift current increases to balance it.

(iv) An AC voltage \( V = 0.5 \sin (100\pi t) \) volt is applied, in turn, across a half-wave rectifier and a full-wave rectifier. The frequency of the output voltage across them respectively will be:

View Solution

Understanding Rectifier Frequency Response

- The given AC voltage is:

\[ V = 0.5 \sin(100\pi t) \]

- The general form of an AC signal is:

\[ V = V_0 \sin(2\pi f t) \]

Comparing, we get:

\[ 2\pi f = 100\pi \]

\[ f = \frac{100\pi}{2\pi} = 50 Hz \]

Half-Wave Rectifier Output Frequency:

- A half-wave rectifier allows only one half-cycle of the input AC voltage.

- The output voltage still follows the same fundamental frequency as the input, i.e., 50 Hz.

Full-Wave Rectifier Output Frequency:

- A full-wave rectifier inverts the negative half-cycles, making the output frequency twice the input frequency.

- Thus, the frequency of the output becomes:

\[ 2 \times 50 = 100 Hz \]

Thus, the correct answer is 50 Hz for the half-wave rectifier and 100 Hz for the full-wave rectifier.

Quick Tip: A half-wave rectifier retains the same frequency as the input AC, whereas a full-wave rectifier doubles the frequency.

Question 30. A lens is a transparent optical medium bounded by two surfaces; at least one of

which should be spherical. Applying the formula of image formation by a single

spherical surface successively at the two surfaces of a thin lens, a formula known as lens

maker’s formula and hence the basic lens formula can be obtained. The focal length (or

power) of a lens depends on the radii of its surfaces and the refractive index of its

material with respect to the surrounding medium. The refractive index of a material

depends on the wavelength of light used. Combination of lenses helps us to obtain

diverging or converging lenses of desired power and magnification.

(i) A thin converging lens of focal length 20 cm and a thin diverging lens of focal length 15 cm are placed coaxially in contact. The power of the combination is:

View Solution

Power of a Combination of Lenses

Step 1: Understanding Power of Lenses

- The power \( P \) of a lens is given by:

\[ P = \frac{100}{f} \quad (in diopters, D) \]

where:

- \( f \) = Focal length in cm.

Step 2: Calculating the Power of Each Lens

- Converging lens (convex):

\[ P_1 = \frac{100}{20} = 5D \]

- Diverging lens (concave):

\[ P_2 = \frac{100}{-15} = -\frac{100}{15} = -\frac{20}{3}D \]

Step 3: Total Power of the Combination

Since the lenses are in contact, the net power is:

\[ P_{net} = P_1 + P_2 \]

\[ P_{net} = 5 - \frac{20}{3} \]

\[ P_{net} = \frac{15}{3} - \frac{20}{3} = -\frac{5}{3} D \]

Step 4: Conclusion

Thus, the power of the combination is:

\[ \boxed{-\frac{5}{3} D} \]

which matches option (B).

Quick Tip: The total power of lenses in contact is the algebraic sum of their individual powers: \( P_{total} = P_1 + P_2 \).

(ii) The radii of curvature of two surfaces of a convex lens are \( R \) and \( 2R \). If the focal length of this lens is \( \frac{4}{3} R \), the refractive index of the material of the lens is:

View Solution

Using Lens Maker’s Formula to Find Refractive Index

Step 1: Lens Maker’s Formula

For a thin convex lens, the lens maker’s equation is:

\[ \frac{1}{f} = (\mu - 1) \left( \frac{1}{R_1} - \frac{1}{R_2} \right) \]

where:

- \( f = \frac{4}{3} R \) (given focal length),

- \( R_1 = R \) and \( R_2 = -2R \) (sign convention: convex surface is positive, concave is negative),

- \( \mu \) = Refractive index of the lens material.

Step 2: Substituting Given Values \[ \frac{3}{4R} = (\mu - 1) \left( \frac{1}{R} - \frac{1}{-2R} \right) \]

\[ \frac{3}{4R} = (\mu - 1) \left( \frac{1}{R} + \frac{1}{2R} \right) \]

\[ \frac{3}{4R} = (\mu - 1) \times \frac{3}{2R} \]

Step 3: Solving for \( \mu \) \[ \mu - 1 = \frac{3}{4} \times \frac{2}{3} \]

\[ \mu - 1 = \frac{2}{4} = \frac{1}{2} \]

\[ \mu = 1 + \frac{1}{2} = \frac{3}{2} \]

Step 4: Conclusion

Thus, the refractive index of the material of the lens is:

\[ \boxed{\frac{3}{2}} \]

which matches option (C).

Quick Tip: The lens maker’s formula helps determine the focal length and refractive index of a lens using its curvature.

(iii) The focal length of an equiconvex lens:

View Solution

Effect of Surrounding Medium on Focal Length

- The focal length of a lens is given by the lens maker’s formula:

\[ \frac{1}{f} = (n_{lens} - n_{medium}) \left( \frac{1}{R_1} - \frac{1}{R_2} \right) \]

where:

- \( n_{lens} \) = Refractive index of the lens material.

- \( n_{medium} \) = Refractive index of the surrounding medium.

- \( R_1, R_2 \) = Radii of curvature of the lens.

Effect of Dipping the Lens in Water

- When the lens is in air, \( n_{medium} = 1 \).

- When dipped in water, \( n_{medium} \approx 1.33 \).

- Since the focal length is inversely proportional to \( (n_{lens} - n_{medium}) \), as \( n_{medium} \) increases, the focal length also increases.

Thus, the correct answer is (A) The focal length increases when the lens is dipped in water.

Quick Tip: The focal length of a lens increases when placed in a medium with a refractive index closer to that of the lens material.

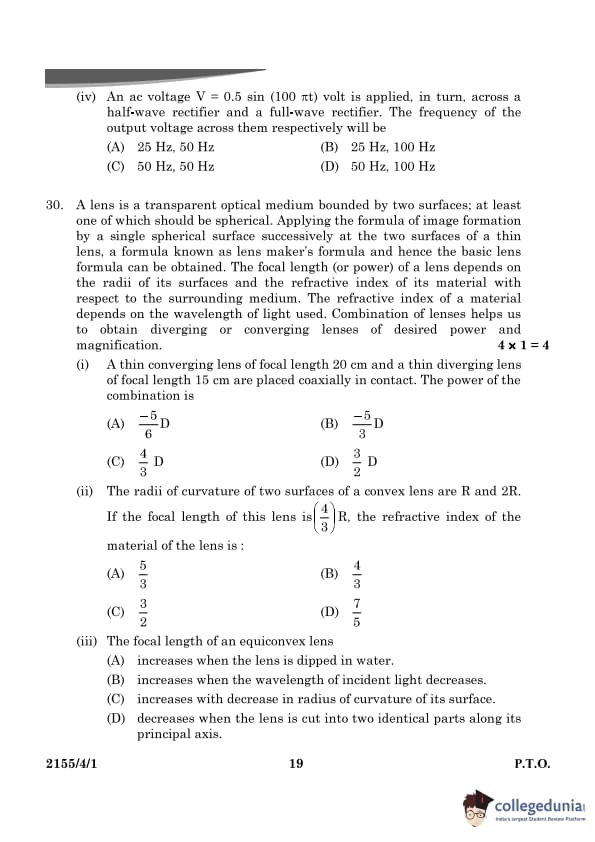

(iv) (a) A thin convex lens \( L \) of focal length 10 cm and a concave mirror \( M \) of focal length 15 cm are placed coaxially 40 cm apart as shown in the figure. A beam of light coming parallel to the principal axis is incident on the lens. The final image will be formed at a distance of:

View Solution

Image Formation by a Convex Lens and Concave Mirror

Step 1: Image Formation by the Convex Lens

- A parallel beam of light incident on a convex lens converges at the focus of the lens.

- Given focal length of the convex lens:

\[ f_L = 10 cm \]

- Since parallel rays converge at the focal point, the image formed by the convex lens is:

\[ I_1 = 10 cm (to the right of the lens) \]

- This image acts as the object for the concave mirror.

Step 2: Object Distance for the Concave Mirror

- Distance between the lens and the mirror:

\[ d = 40 cm \]

- Distance of the image formed by the lens from the mirror:

\[ u_M = 40 - 10 = 30 cm \]

- Focal length of the concave mirror:

\[ f_M = -15 cm \quad (negative for concave mirror) \]

Using the mirror formula:

\[ \frac{1}{v} + \frac{1}{u} = \frac{1}{f} \]

\[ \frac{1}{v} + \frac{1}{30} = \frac{1}{-15} \]

\[ \frac{1}{v} = \frac{1}{-15} - \frac{1}{30} \]

\[ \frac{1}{v} = -\frac{2}{30} - \frac{1}{30} = -\frac{3}{30} = -\frac{1}{10} \]

\[ v = -10 cm \]

Step 3: Final Image Position

- The negative sign indicates that the final image is on the same side as the mirror.

- Distance from the mirror: 10 cm.

- Since the mirror is 40 cm from the lens, the final image is:

\[ 40 - 10 = 30 cm from the lens, on the right. \]

- Since the image distance from the lens is greater than the focal length, the final image is real and inverted.

Step 4: Conclusion

- Final image is formed at 10 cm to the right of the lens.

- Thus, the correct answer is:

\[ \boxed{(B) 10 cm, right of lens} \] Quick Tip: A concave mirror inverts the image from a convex lens, forming the final image on the same side as the mirror.

(iv) (b) A beam of light coming parallel to the principal axis of a convex lens \( L_1 \) of focal length 16 cm is incident on it. Another convex lens \( L_2 \) of focal length 12 cm is placed coaxially at a distance 40 cm from \( L_1 \). The nature and distance of the final image from \( L_2 \) will be:

View Solution

Image Formation Using Two Convex Lenses

- The first lens \( L_1 \) forms an image of an object at infinity at its focal point:

\[ u_1 = \infty, \quad f_1 = 16 cm \]

\[ v_1 = f_1 = 16 cm \]

- This image acts as the object for the second convex lens \( L_2 \), placed 40 cm away:

\[ u_2 = 40 - 16 = 24 cm, \quad f_2 = 12 cm \]

Using the lens formula:

\[ \frac{1}{v_2} - \frac{1}{u_2} = \frac{1}{f_2} \]

\[ \frac{1}{v_2} - \frac{1}{24} = \frac{1}{12} \]

\[ \frac{1}{v_2} = \frac{1}{12} + \frac{1}{24} = \frac{2}{24} + \frac{1}{24} = \frac{3}{24} \]

\[ v_2 = 24 cm \]

- The positive value indicates a real image formed 24 cm from \( L_2 \).

Thus, the correct answer is (A) Real, 24 cm.

Quick Tip: When a convex lens forms an image at its focal point, it acts as an object for the next lens, and the final image position is determined using the lens equation.

(i) Draw a ray diagram for the formation of the image of an object by a convex mirror. Hence, obtain the mirror equation.

View Solution

Image Formation by a Convex Mirror

- A convex mirror always forms a virtual, erect, and diminished image behind the mirror.

- The image is always located between the pole and focus of the mirror.

Derivation of the Mirror Equation

Using the sign convention:

- The mirror formula is given by:

\[ \frac{1}{f} = \frac{1}{v} + \frac{1}{u} \]

where:

- \( f \) = Focal length of the mirror

- \( u \) = Object distance

- \( v \) = Image distance

For a convex mirror, \( f \) and \( v \) are positive, while \( u \) is negative.

Thus, the mirror equation holds for both concave and convex mirrors. Quick Tip: A convex mirror always forms a virtual, erect, and diminished image, making it ideal for rearview mirrors.

(ii) Why are multi-component lenses used for both the objective and the eyepiece in optical instruments?

View Solution

Importance of Multi-Component Lenses

- Multi-component lenses are used in optical instruments to correct optical aberrations such as:

1. Chromatic aberration: Different wavelengths focus at different points.

2. Spherical aberration: Light rays at different distances from the optical axis do not converge at the same point.

3. Astigmatism and distortion: Deformation of the image shape.

- These lenses consist of convex and concave elements made of materials with different refractive indices.

- In objectives: Multi-component lenses enhance image clarity and reduce distortion.

- In eyepieces: They improve magnification and reduce eye strain. Quick Tip: Multi-component lenses reduce optical aberrations and enhance image clarity, making them essential for high-precision optical instruments.

(iii) The magnification of a small object produced by a compound microscope is 200. The focal length of the eyepiece is 2 cm and the final image is formed at infinity. Find the magnification produced by the objective.

View Solution

Calculation of Objective Magnification

- The total magnification of a compound microscope is given by:

\[ M = M_o \times M_e \]

where:

- \( M \) = Total magnification = 200

- \( M_o \) = Magnification by the objective (to be found)

- \( M_e \) = Magnification by the eyepiece

- The magnification of the eyepiece is:

\[ M_e = \frac{D}{f_e} \]

where:

- \( D = 25 \) cm (Near point of the human eye)

- \( f_e = 2 \) cm

\[ M_e = \frac{25}{2} = 12.5 \]

- Using the total magnification equation:

\[ 200 = M_o \times 12.5 \]

\[ M_o = \frac{200}{12.5} = 16 \]

Thus, the magnification produced by the objective is 16.

Quick Tip: In a compound microscope, the objective provides initial magnification, which is further magnified by the eyepiece.

(i) Differentiate between a wavefront and a ray.

View Solution

Difference Between Wavefront and Ray

A wavefront is the locus of all points that are in the same phase of vibration.

A ray is an imaginary line that represents the direction of wave propagation.

It is always perpendicular to the direction of wave propagation.

It is always perpendicular to the wavefront.

Examples: Plane wavefront, spherical wavefront.

Used to represent light beams in geometrical optics.

Quick Tip: A wavefront shows the shape of the propagating wave, while a ray shows its direction.

(ii) State Huygen's principle and verify laws of reflection using a suitable diagram.

View Solution

Huygen’s Principle

- Huygen’s Principle states that:

1. Every point on a wavefront acts as a source of secondary wavelets.

2. The envelope of these secondary wavelets forms the new wavefront.

Verification of Laws of Reflection Using Huygen’s Principle

- Consider a plane wavefront incident on a reflecting surface.

- Each point on the wavefront acts as a secondary source, and the reflected wavefront follows the law of reflection.

Verification of Reflection Law

Using Huygen’s Principle:

- Angle of incidence (\(\theta_i\)) = Angle of reflection (\(\theta_r\)).

- This verifies the Law of Reflection. Quick Tip: Huygen’s principle explains how reflection occurs by treating each wavefront as a secondary source of new waves.

(iii) In Young's double slit experiment, the slits \( S_1 \) and \( S_2 \) are 3 mm apart, and the screen is placed 1.0 m away from the slits. The fourth bright fringe is at a distance of 5 mm from the second dark fringe. Find the wavelength of light used.

View Solution

Wavelength Calculation

% Solution

Solution: Finding the Wavelength of Light in Young’s Double Slit Experiment

Step 1: Understanding the Double Slit Experiment

In Young's double slit experiment, the fringe separation \( y \) is given by the formula:

\[ y = \frac{\lambda D}{d} \]

where:

- \( \lambda \) = wavelength of light,

- \( D \) = distance between the screen and the slits,

- \( d \) = distance between the two slits.

Step 2: Understanding the Fringe Spacing

In the problem, the distance between the second dark fringe and the fourth bright fringe is given as 5 mm.

For Young’s double slit experiment, the distance between consecutive dark fringes or bright fringes is the same, and the distance between the second dark fringe and the fourth bright fringe is:

\[ Distance = 4y - 2y = 2y \]

Thus, \( 2y = 5 mm \), so the fringe separation \( y \) is:

\[ y = \frac{5}{2} = 2.5 mm = 2.5 \times 10^{-3} m \]

Step 3: Using the Fringe Separation Formula

Now, using the fringe separation formula:

\[ y = \frac{\lambda D}{d} \]

Substitute the known values:

- \( y = 2.5 \times 10^{-3} m \),

- \( D = 1.0 m \),

- \( d = 3 \times 10^{-3} m \).

\[ 2.5 \times 10^{-3} = \frac{\lambda \times 1.0}{3 \times 10^{-3}} \]

\[ \lambda = \frac{2.5 \times 10^{-3} \times 3 \times 10^{-3}}{1.0} \]

\[ \lambda = 8.33 \times 10^{-7} m \]

\[ \lambda = 833 nm \]

Thus, the wavelength of the light used is:

\[ \boxed{833 \, nm} \] Quick Tip: Young’s double-slit experiment determines the wavelength of light using the fringe width equation \( \beta = \frac{\lambda D}{d} \).

(i) A dielectric slab of dielectric constant \( K \) and thickness \( t \) is inserted between plates of a parallel plate capacitor of plate separation \( d \) and plate area \( A \). Obtain an expression for its capacitance.

View Solution

Capacitance with a Dielectric Slab

- The capacitance of a parallel plate capacitor in vacuum is:

\[ C_0 = \frac{\epsilon_0 A}{d} \]

where:

- \( \epsilon_0 \) = Permittivity of free space,

- \( A \) = Plate area,

- \( d \) = Plate separation.

- When a dielectric slab of thickness \( t \) and dielectric constant \( K \) is inserted:

- The remaining air gap in the capacitor is \( (d - t) \).

- The system now behaves as two capacitors in series:

1. Capacitor with dielectric: \( C_1 = \frac{K \epsilon_0 A}{t} \).

2. Capacitor with air gap: \( C_2 = \frac{\epsilon_0 A}{d - t} \).

- The effective capacitance is:

\[ \frac{1}{C} = \frac{1}{C_1} + \frac{1}{C_2} \]

\[ \frac{1}{C} = \frac{t}{K \epsilon_0 A} + \frac{(d - t)}{\epsilon_0 A} \]

\[ C = \frac{\epsilon_0 A}{\frac{t}{K} + (d - t)} \]

Thus, the capacitance of the capacitor with a dielectric slab is:

\[ C = \frac{\epsilon_0 A}{d - t + \frac{t}{K}} \] Quick Tip: A dielectric increases the capacitance of a capacitor, but if it doesn't fully fill the gap, the system behaves as capacitors in series.

(ii) Two capacitors of different capacitances are connected first (1) in series and then (2) in parallel across a dc source of 100 V. If the total energy stored in the combination in the two cases is 40 mJ and 250 mJ respectively, find the capacitance of the capacitors.

View Solution

Finding Capacitance of the Capacitors

Step 1: Energy in a Capacitor

The energy stored in a capacitor is:

\[ U = \frac{1}{2} C V^2 \]

where:

- \( C \) = Capacitance,

- \( V \) = Voltage applied.

Given:

- Series combination energy: \( U_s = 40 \) mJ = \( 40 \times 10^{-3} \) J,

- Parallel combination energy: \( U_p = 250 \) mJ = \( 250 \times 10^{-3} \) J,

- Applied voltage: \( V = 100 \) V.

Step 2: Parallel Combination

For parallel capacitors:

\[ C_p = C_1 + C_2 \]

\[ U_p = \frac{1}{2} C_p V^2 \]

\[ 250 \times 10^{-3} = \frac{1}{2} (C_1 + C_2) (100)^2 \]

\[ 250 \times 10^{-3} = 5000 (C_1 + C_2) \]

\[ C_1 + C_2 = \frac{250 \times 10^{-3}}{5000} = 50 \times 10^{-6} = 50 \mu F \]

Step 3: Series Combination

For series capacitors:

\[ \frac{1}{C_s} = \frac{1}{C_1} + \frac{1}{C_2} \]

\[ U_s = \frac{1}{2} C_s V^2 \]

\[ 40 \times 10^{-3} = \frac{1}{2} C_s (100)^2 \]

\[ 40 \times 10^{-3} = 5000 C_s \]

\[ C_s = \frac{40 \times 10^{-3}}{5000} = 8 \times 10^{-6} = 8 \mu F \]

Step 4: Solving for \( C_1 \) and \( C_2 \)

Using:

\[ C_s = \frac{C_1 C_2}{C_1 + C_2} \]

\[ 8 = \frac{C_1 C_2}{50} \]

\[ C_1 C_2 = 8 \times 50 = 400 \]

Solving the quadratic equation:

\[ x^2 - 50x + 400 = 0 \]

Using the quadratic formula:

\[ x = \frac{50 \pm \sqrt{2500 - 1600}}{2} \]

\[ x = \frac{50 \pm 30}{2} \]

\[ x = \frac{80}{2} = 40 \quad or \quad x = \frac{20}{2} = 10 \]

Thus, the capacitances are \( C_1 = 40 \) \muF and \( C_2 = 10 \) \muF.

Quick Tip: For capacitors in parallel: \( C_p = C_1 + C_2 \). For capacitors in series: \( \frac{1}{C_s} = \frac{1}{C_1} + \frac{1}{C_2} \).

(i) Using Gauss's law, show that the electric field \( E \) at a point due to a uniformly charged infinite plane sheet is given by \( E = \frac{\sigma}{2\epsilon_0} \), where symbols have their usual meanings.

View Solution

Derivation of Electric Field Due to an Infinite Plane Sheet

Step 1: Gauss’s Law Statement

According to Gauss’s Law:

\[ \oint \mathbf{E} \cdot d\mathbf{A} = \frac{Q_{enc}}{\epsilon_0} \]

where:

- \( \oint \mathbf{E} \cdot d\mathbf{A} \) = Total electric flux,

- \( Q_{enc} \) = Enclosed charge,

- \( \epsilon_0 \) = Permittivity of free space.

Step 2: Choosing a Gaussian Surface

- Consider an infinite charged plane with surface charge density \( \sigma \).

- The charge is uniformly distributed over the plane.

- We use a Gaussian cylinder (pillbox) that extends equally on both sides of the plane.

Step 3: Applying Gauss’s Law

- The flux is perpendicular to the surface.

- The total flux through the two flat surfaces of the pillbox is:

\[ \oint \mathbf{E} \cdot d\mathbf{A} = E A + E A = 2E A \]

- The enclosed charge is:

\[ Q_{enc} = \sigma A \]

- Applying Gauss's Law:

\[ 2E A = \frac{\sigma A}{\epsilon_0} \]

\[ E = \frac{\sigma}{2\epsilon_0} \]

Thus, the electric field due to an infinite plane sheet is:

\[ E = \frac{\sigma}{2\epsilon_0} \] Quick Tip: The electric field due to an infinite sheet does not depend on the distance from the sheet, unlike a point charge or a line charge.

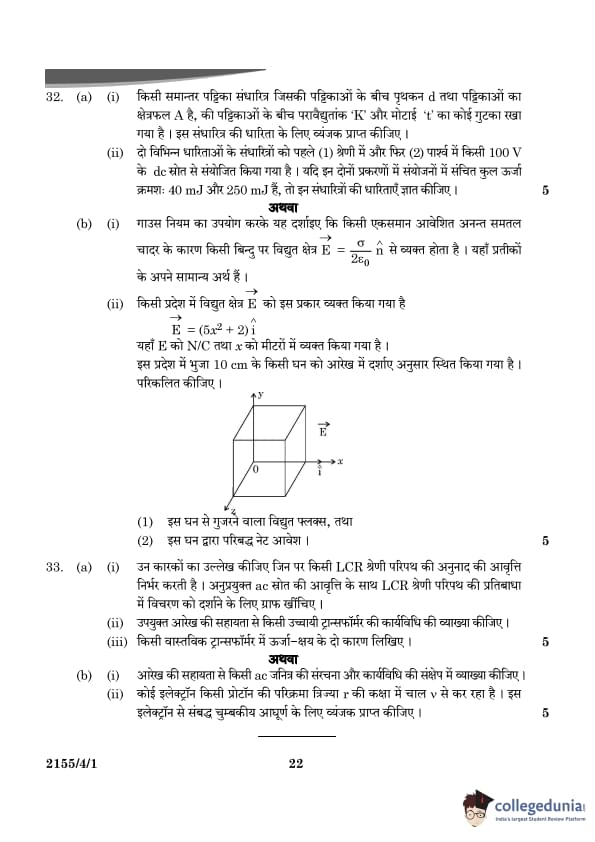

(ii) Electric field \( E \) in a region is given by \( E = (5x^2 + 2) \hat{i} \), where \( E \) is in N/C and \( x \) is in meters. A cube of side 10 cm is placed in the region as shown in the figure. Calculate:

(1) The electric flux through the cube, and

(2) The net charge enclosed by the cube

View Solution

Flux and Enclosed Charge Calculation

Step 1: Understanding the Given Field

The electric field is:

\[ E = (5x^2 + 2) \hat{i} \]

- The electric field varies with \( x \) but is uniform along the \( y \) and \( z \)-directions.

- The cube has a side length of 10 cm = 0.1 m.

Step 2: Flux Calculation

Electric flux is given by:

\[ \Phi_E = \oint \mathbf{E} \cdot d\mathbf{A} \]

Since the field is in the \( x \)-direction, it only contributes to the flux through the two faces perpendicular to \( x \)-axis.

- At \( x = 0 \) (left face), the field is:

\[ E_{left} = (5(0)^2 + 2) = 2 N/C \]

- At \( x = 0.1 \) m (right face), the field is:

\[ E_{right} = (5(0.1)^2 + 2) = 2 + 5(0.01) = 2.05 N/C \]

Flux through the cube:

\[ \Phi_E = E_{right} A - E_{left} A \]

\[ = (2.05 - 2) (0.1 \times 0.1) \]

\[ = (0.05) (0.01) \]

\[ = 5 \times 10^{-4} Nm^2/C \]

Step 3: Charge Enclosed Using Gauss’s Law

From Gauss’s Law:

\[ \Phi_E = \frac{Q_{enc}}{\epsilon_0} \]

\[ Q_{enc} = \epsilon_0 \Phi_E \]

\[ = (8.85 \times 10^{-12}) (5 \times 10^{-4}) \]

\[ = 4.43 \times 10^{-15} C \]

Thus, the net charge enclosed by the cube is \( 4.43 \times 10^{-15} \) C.

Quick Tip: For a non-uniform field, calculate the flux difference through opposite faces to determine the net charge enclosed.

(i) Mention the factors on which the resonant frequency of a series LCR circuit depends. Plot a graph showing variation of impedance of a series LCR circuit with the frequency of the applied AC source.

View Solution

Factors Affecting Resonant Frequency

- The resonant frequency \( f_r \) of a series LCR circuit is given by:

\[ f_r = \frac{1}{2\pi \sqrt{LC}} \]

It depends on:

1. Inductance (L): Increasing \( L \) decreases the resonant frequency.

2. Capacitance (C): Increasing \( C \) decreases the resonant frequency.

Graph: Variation of Impedance with Frequency

- The impedance \( Z \) of a series LCR circuit is:

\[ Z = \sqrt{R^2 + (X_L - X_C)^2} \]

where:

- \( X_L = \omega L \) (Inductive reactance),

- \( X_C = \frac{1}{\omega C} \) (Capacitive reactance).

At resonance (\( f = f_r \)):

- \( X_L = X_C \) → Minimum impedance (Only \( R \) remains).

- High current flows through the circuit. Quick Tip: The resonant frequency \( f_r \) is inversely proportional to \( \sqrt{LC} \). At resonance, impedance is minimum, and current is maximum.

(ii) With the help of a suitable diagram, explain the working of a step-up transformer.

View Solution

Step-Up Transformer

Working of a Step-Up Transformer

- A step-up transformer increases the voltage while reducing the current.

- It consists of two coils: Primary (\( N_p \)) and Secondary (\( N_s \)).

- The number of turns in the secondary coil is greater than in the primary.

Transformer Equation

The voltage transformation ratio is:

\[ \frac{V_s}{V_p} = \frac{N_s}{N_p} \]

where:

- \( V_p \), \( V_s \) = Voltages in primary and secondary coils.

- \( N_p \), \( N_s \) = Number of turns in primary and secondary coils.

Since \( N_s > N_p \), \( V_s > V_p \) (Step-Up Transformer). Quick Tip: Step-up transformers are used in power transmission to reduce current and minimize energy loss in transmission lines.

(iii) Write two causes of energy loss in a real transformer.

View Solution

Energy Losses in Transformers

1. Eddy Current Loss:

- Induced currents in the iron core cause energy dissipation as heat.

- Minimized using laminated cores.

2. Hysteresis Loss:

- Energy loss due to repeated magnetization and demagnetization of the core.

- Reduced by using soft iron cores. Quick Tip: Using laminated cores and soft iron reduces transformer losses and improves efficiency.

(i) With the help of a diagram, briefly explain the construction and working of an AC generator.

View Solution

Construction and Working of an AC Generator

Construction of an AC Generator

An AC generator converts mechanical energy into electrical energy based on electromagnetic induction. It consists of:

1. Armature Coil (\( ABCD \)): A rectangular coil rotates inside a magnetic field.

2. Magnetic Field: Created using permanent magnets or electromagnets.

3. Slip Rings (\( S_1, S_2 \)): Connected to the coil, providing continuous contact.

4. Brushes: Connect the slip rings to the external circuit.

Working of an AC Generator

- The coil rotates in the magnetic field due to external mechanical energy.

- According to Faraday’s Law of Electromagnetic Induction, an EMF is induced:

\[ \mathcal{E} = B L v \sin\theta \]

- The induced current alternates because the coil changes orientation every half cycle.

- The output AC voltage follows:

\[ \mathcal{E} = \mathcal{E}_0 \sin \omega t \] Quick Tip: An AC generator produces an alternating voltage, which is converted to DC using a commutator in a DC generator.

(ii) An electron is revolving around a proton in an orbit of radius \( r \) with a speed \( v \). Obtain an expression for the magnetic moment associated with the electron.

View Solution

Magnetic Moment of an Orbiting Electron

Step 1: Current Due to Electron Motion

- The electron moves in a circular orbit around the nucleus, creating a loop current.

- The current \( I \) is:

\[ I = \frac{Charge per revolution}{Time for one revolution} \]

- The charge of an electron is \( e \) and time period \( T \) is:

\[ T = \frac{2\pi r}{v} \]

\[ I = \frac{e}{T} = \frac{e}{2\pi r / v} = \frac{e v}{2\pi r} \]

Step 2: Magnetic Moment Calculation

- The magnetic moment (\( \mu \)) is:

\[ \mu = I \times A \]

- Since the electron follows a circular path, the area is:

\[ A = \pi r^2 \]

\[ \mu = \left( \frac{e v}{2\pi r} \right) \times \pi r^2 \]

\[ \mu = \frac{e v r}{2} \]

Step 3: Expressing in Terms of Angular Momentum

- The angular momentum of the electron is:

\[ L = m v r \]

where \( m \) is the mass of the electron.

- Since:

\[ \mu = \frac{e v r}{2} \]

Replacing \( v r \) using \( L \):

\[ \mu = \frac{e}{2m} L \]

Thus, the magnetic moment associated with the electron is:

\[ \mu = \frac{e}{2m} L \] Quick Tip: The ratio \( \frac{e}{2m} \) is called the gyromagnetic ratio and is crucial in quantum mechanics and nuclear magnetism.

Comments