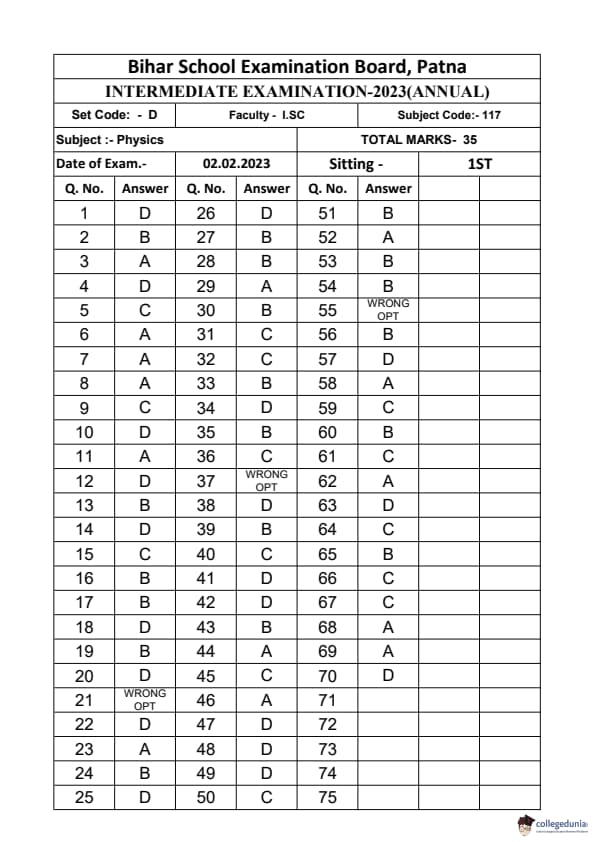

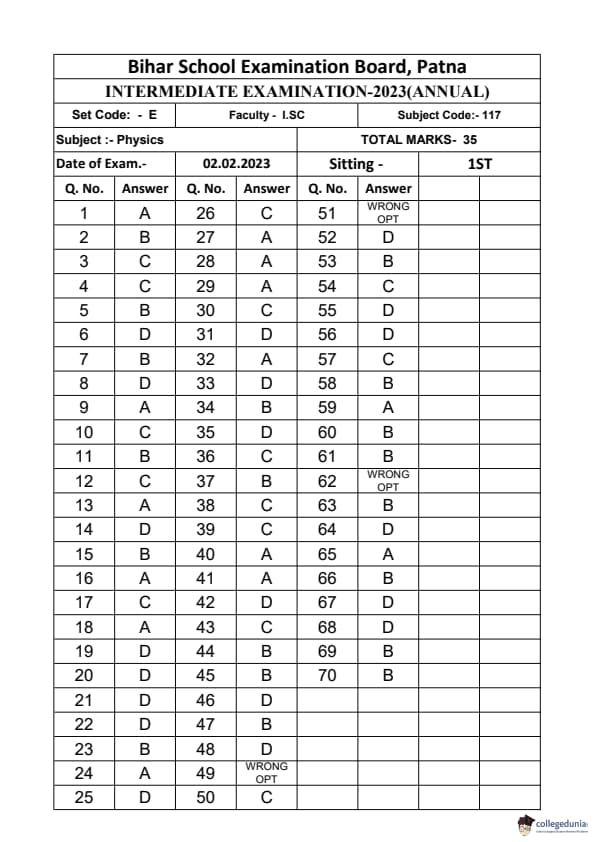

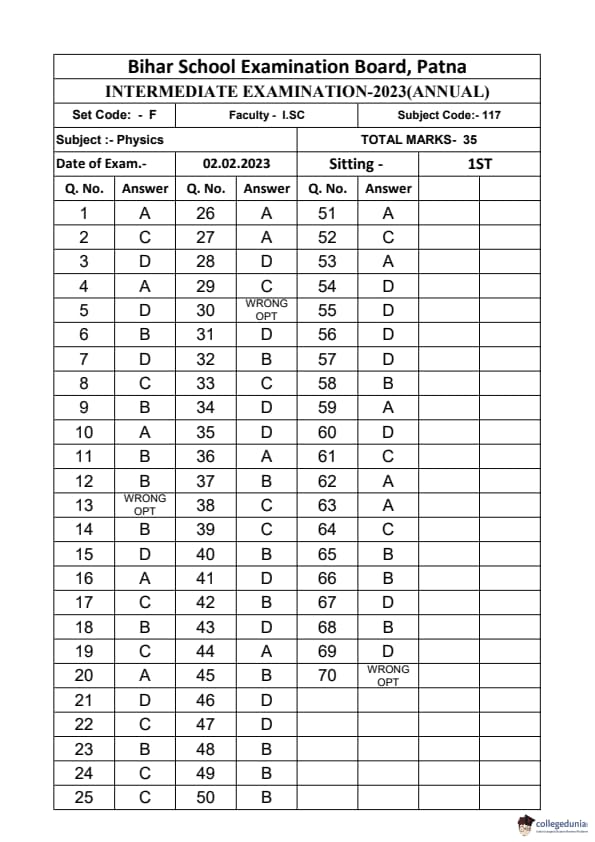

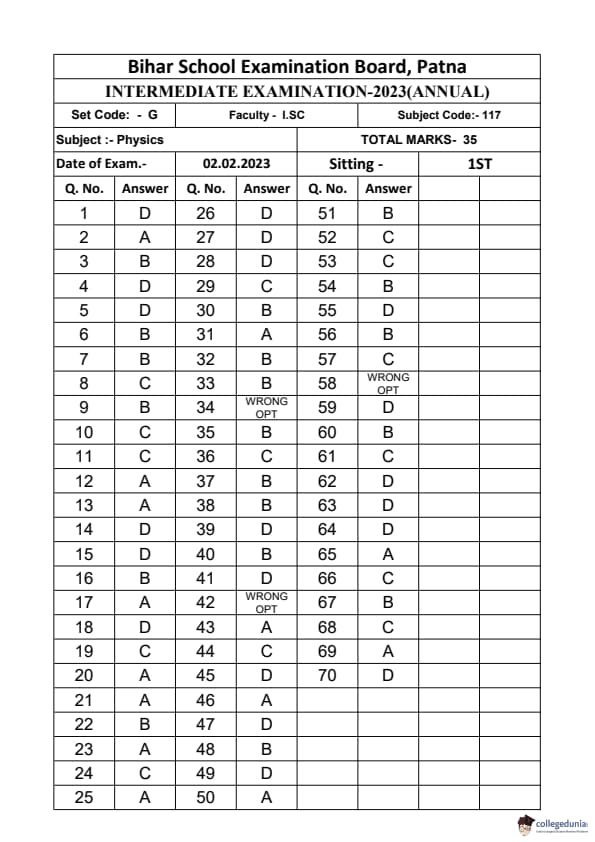

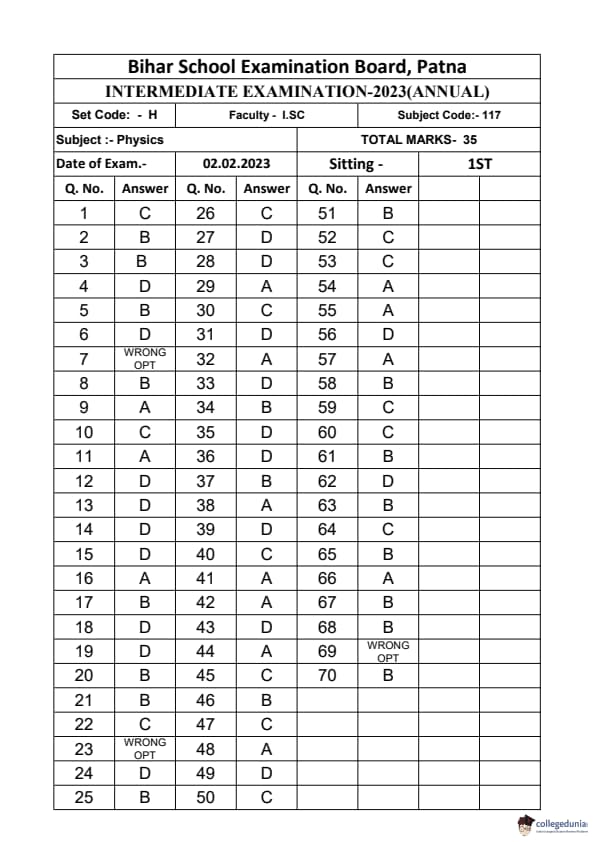

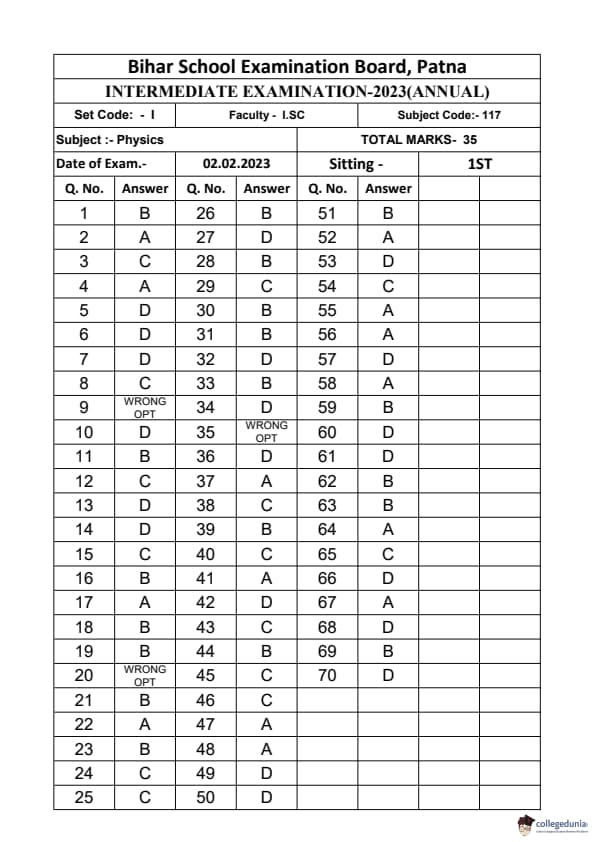

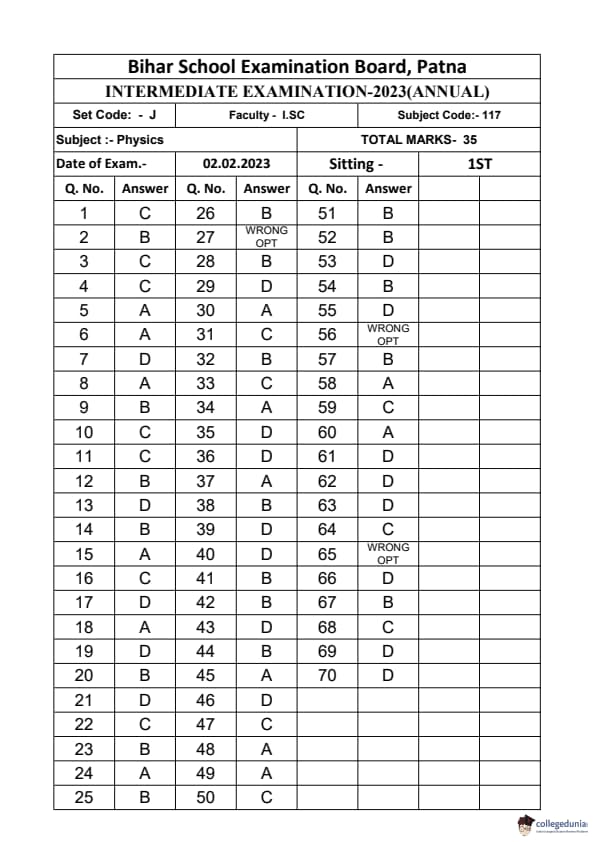

Bihar Board Class 12 Physics Elective Question Paper 2023 with Answer Key pdf is available for download here. The exam was conducted by Bihar School Examination Board (BSEB). The question paper comprised a total of 96 questions divided among 2 sections.

Bihar Board Class 12 Physics Elective Question Paper 2023 with Answer Key

| Bihar Board Class 12 Physics Question Paper with Answer Key | Check Solutions |

When current in a coil changes from 5A to 2A in 0.1s then average voltage of 50V is produced. The self-inductance of the coil is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

The question asks for the self-inductance of a coil. Self-inductance is the property of a coil by virtue of which it opposes any change in the strength of the current flowing through it by inducing an electromotive force (e.m.f.) in itself. This induced e.m.f. is also known as back e.m.f. The magnitude of this induced e.m.f. is directly proportional to the rate of change of current.

Step 2: Key Formula or Approach:

The formula for the average induced voltage (e.m.f., \(\epsilon\)) in a coil due to self-inductance (L) is given by Faraday's law of induction:

\[ \epsilon = -L \frac{dI}{dt} \]

Where:

\(\epsilon\) is the induced voltage (e.m.f.).

\(L\) is the self-inductance of the coil.

\(\frac{dI}{dt}\) is the rate of change of current.

For average values over a time interval \(\Delta t\), the formula can be written as:

\[ \epsilon_{avg} = -L \frac{\Delta I}{\Delta t} \]

The negative sign indicates that the induced e.m.f. opposes the change in current (Lenz's Law). For calculating the magnitude, we can use:

\[ |\epsilon_{avg}| = L \left| \frac{\Delta I}{\Delta t} \right| \]

Step 3: Detailed Explanation:

Given data:

Initial current, \(I_1 = 5 A\)

Final current, \(I_2 = 2 A\)

Time interval, \(\Delta t = 0.1 s\)

Average induced voltage, \(\epsilon = 50 V\)

First, we calculate the change in current (\(\Delta I\)):

\[ \Delta I = I_2 - I_1 = 2 A - 5 A = -3 A \]

Next, we calculate the rate of change of current \(\frac{\Delta I}{\Delta t}\):

\[ \frac{\Delta I}{\Delta t} = \frac{-3 A}{0.1 s} = -30 A/s \]

Now, we use the formula for induced voltage to find the self-inductance \(L\):

\[ \epsilon = -L \frac{\Delta I}{\Delta t} \] \[ 50 V = -L (-30 A/s) \] \[ 50 = 30L \]

Solving for \(L\):

\[ L = \frac{50}{30} H \] \[ L = \frac{5}{3} H \] \[ L \approx 1.67 H \]

Step 4: Final Answer:

The self-inductance of the coil is approximately 1.67 Henry. This corresponds to option (A).

Quick Tip: In problems involving induced e.m.f., always pay attention to the signs. The negative sign in Faraday's law (\(\epsilon = -L \frac{dI}{dt}\)) represents Lenz's law, which states that the induced e.m.f. opposes the change in current. When calculating the magnitude of inductance, you can often ignore the sign, but understanding its meaning is crucial for conceptual questions.

The concept of secondary wavelets was given by

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

The question asks to identify the scientist who proposed the concept of secondary wavelets. This concept is a fundamental part of the wave theory of light, used to explain phenomena like reflection, refraction, and diffraction.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

The concept of secondary wavelets was introduced by the Dutch physicist Christiaan Huygens in 1678.

Huygens' Principle states that:

1. Every point on a primary wavefront acts as a source of new disturbances, called secondary wavelets, which travel out in all directions with the same speed as the original wave.

2. The new wavefront at any later time is the forward envelope (the tangential surface in the forward direction) of these secondary wavelets.

This principle successfully explains the propagation of waves and phenomena like reflection and refraction. While Fresnel later modified and refined Huygens' principle to better explain diffraction (leading to the Huygens-Fresnel principle), the original concept of secondary wavelets is credited to Huygens.

- Fresnel built upon Huygens' work to explain diffraction by incorporating the principle of interference of the secondary wavelets.

- Maxwell developed the electromagnetic theory of light, describing light as electromagnetic waves.

- Newton proposed the corpuscular (particle) theory of light.

Step 3: Final Answer:

The concept of secondary wavelets was given by Huygens. Therefore, option (C) is the correct answer.

Quick Tip: Remember the key contributions of scientists in wave optics: Huygens gave the principle of secondary wavelets, Young demonstrated interference (double-slit experiment), and Fresnel explained diffraction by combining Huygens' principle with interference. Newton is associated with the particle theory of light, which contrasts with the wave theory.

In photoelectric effect, the photoelectric current is independent of

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

The photoelectric effect is the emission of electrons when electromagnetic radiation, such as light, hits a material. Photoelectric current is the flow of these emitted electrons (photoelectrons). The question asks which factor does not affect the magnitude of this current.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

Let's analyze the relationship between photoelectric current and the given options:

(A) Intensity of incident light: Photoelectric current is directly proportional to the intensity of the incident light (provided the frequency is above the threshold frequency). Higher intensity means more photons are striking the surface per unit time, which in turn ejects more electrons, leading to a larger current. So, the current is dependent on intensity.

(B) Potential difference applied between two electrodes: The potential difference can either accelerate or decelerate the photoelectrons. An accelerating potential helps more electrons reach the collector, increasing the current up to a saturation point. A retarding (negative) potential opposes the flow, decreasing the current. Thus, the current is dependent on the potential difference.

(C) The nature of emitter material: The material's nature determines its work function (\(\phi_0\)), which is the minimum energy required to eject an electron. This defines the threshold frequency (\(f_0\)). If the incident light's frequency is below \(f_0\), no current flows. So, the existence of the current depends on the material.

(D) Frequency of incident light: According to Einstein's photoelectric equation (\(K_{max} = hf - \phi_0\)), the frequency of the incident light determines the maximum kinetic energy of the emitted photoelectrons, not their number. As long as the frequency is above the threshold frequency (\(f > f_0\)), changing the frequency (while keeping the intensity constant) will change the speed of the electrons, but not the number of electrons emitted per second. Since the photoelectric current depends on the number of electrons emitted per second, it is independent of the frequency of the incident light.

Step 3: Final Answer:

The photoelectric current is independent of the frequency of the incident light (assuming the frequency is above the threshold). Therefore, option (D) is the correct answer.

Quick Tip: To easily remember the relationships in the photoelectric effect: \textbf{Intensity} \(\rightarrow\) \textbf{Number of electrons} \(\rightarrow\) \textbf{Photoelectric Current}. \textbf{Frequency} \(\rightarrow\) \textbf{Energy of electrons} \(\rightarrow\) \textbf{Kinetic Energy / Stopping Potential}. This helps distinguish between what affects the current and what affects the energy of the electrons.

In visible spectrum, which colour has larger wavelength ?

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

The visible spectrum is the portion of the electromagnetic spectrum that is visible to the human eye. It consists of a range of colors, each corresponding to a different wavelength of light. The question asks to identify the color with the largest wavelength.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

The colors of the visible spectrum are typically remembered by the acronym VIBGYOR, which stands for Violet, Indigo, Blue, Green, Yellow, Orange, and Red.

This sequence is arranged in order of increasing wavelength (or decreasing frequency and energy).

- Violet has the shortest wavelength (around 400 nm).

- Red has the longest wavelength (around 650-700 nm).

Therefore, among the given options, Red has the largest wavelength.

Step 3: Final Answer:

In the visible spectrum, Red has the largest wavelength. So, option (A) is correct.

Quick Tip: Use the acronym VIBGYOR to remember the order of colors in the visible spectrum. The order goes from the shortest wavelength (Violet) to the longest wavelength (Red). This also means Violet light has the highest frequency and energy, while Red light has the lowest.

The nucleus of any atom is made up of

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

This question asks about the composition of the atomic nucleus, which is the central, dense region of an atom.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

The nucleus of an atom is composed of two types of subatomic particles:

- Protons, which have a positive electrical charge.

- Neutrons, which are electrically neutral (have no charge).

These two particles, protons and neutrons, are collectively known as nucleons. They are held together in the nucleus by the strong nuclear force.

Let's analyze the other options:

- (A) proton: The nucleus contains protons, but for all elements except the most common isotope of hydrogen (protium), it also contains neutrons. So this is incomplete.

- (B) proton and electron: Electrons are negatively charged particles that orbit the nucleus; they are not part of the nucleus itself.

- (C) \(\alpha\)-particle: An alpha particle is the nucleus of a helium atom, consisting of two protons and two neutrons. While it is a type of nucleus, not all atomic nuclei are α-particles.

Step 3: Final Answer:

The nucleus of an atom is made up of protons and neutrons. Therefore, option (D) is the correct answer.

Quick Tip: Remember the basic structure of an atom: a central nucleus containing protons and neutrons, surrounded by a cloud of orbiting electrons. The number of protons defines the element, while the number of neutrons defines the isotope.

The phase-difference between current and voltage in only capacitive alternating current circuit is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

In an alternating current (AC) circuit containing only a capacitor, the flow of current is related to the rate of change of voltage across the capacitor. This relationship causes a phase difference between the current and voltage waveforms.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

Let the alternating voltage applied to the circuit be \(V = V_m \sin(\omega t)\).

The charge on the capacitor at any instant is \(q = CV = CV_m \sin(\omega t)\).

The current in the circuit is the rate of flow of charge, so we differentiate the charge with respect to time:

\[ I = \frac{dq}{dt} = \frac{d}{dt} (CV_m \sin(\omega t)) \] \[ I = CV_m \omega \cos(\omega t) \]

To compare the phase of current and voltage, we express the current in terms of a sine function:

Since \(\cos(\theta) = \sin(\theta + \frac{\pi}{2})\), we can write:

\[ I = I_m \sin(\omega t + \frac{\pi}{2}) \]

Where \(I_m = V_m \omega C\) is the peak current.

Comparing the phase of voltage, \(\phi_V = \omega t\), with the phase of current, \(\phi_I = \omega t + \frac{\pi}{2}\), we find the phase difference:

\[ \Delta \phi = \phi_I - \phi_V = (\omega t + \frac{\pi}{2}) - \omega t = \frac{\pi}{2} \]

A phase difference of \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) radians is equal to 90°. The positive sign indicates that the current leads the voltage by 90°.

Step 3: Final Answer:

The phase-difference between current and voltage in a purely capacitive AC circuit is 90° (or \(\pi/2\) radians), with the current leading the voltage. Therefore, option (B) is correct.

Quick Tip: A useful mnemonic to remember the phase relationship in AC circuits is "CIVIL": In a \textbf{C}apacitor (C), \textbf{I} (current) leads \textbf{V} (voltage). In an \textbf{I}nductor (L), \textbf{V} (voltage) leads \textbf{I} (current). This helps you quickly recall that for a capacitor, the phase difference is 90° with current ahead.

Which one of the following electromagnetic radiations has minimum wavelength ?

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

The electromagnetic (EM) spectrum is the range of all types of EM radiation. Radiation is classified by wavelength, frequency, or energy. Wavelength (\(\lambda\)) and frequency (\(f\)) are inversely related (\(c = f\lambda\)), and energy (\(E\)) is directly proportional to frequency (\(E = hf\)). Therefore, minimum wavelength corresponds to maximum frequency and maximum energy.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

Let's arrange the given electromagnetic radiations in order of decreasing wavelength (or increasing frequency/energy):

1. Microwaves: Wavelengths range from about 1 meter to 1 millimeter. They have longer wavelengths and lower energy than the other options.

2. Ultraviolet (UV): Wavelengths are shorter than visible light, typically from 400 nm to 10 nm.

3. X-rays: Wavelengths are shorter than UV rays, typically from 10 nm to 0.01 nm.

4. γ-rays (Gamma rays): They have the shortest wavelengths in the entire electromagnetic spectrum, typically less than 0.01 nm (or 10 picometers). They are the most energetic form of electromagnetic radiation.

The order from longest to shortest wavelength is: Microwaves > Ultraviolet > X-rays > γ-rays.

Step 3: Final Answer:

Among the given options, γ-rays have the minimum wavelength. Therefore, option (D) is correct.

Quick Tip: Remember the order of the electromagnetic spectrum: "Roman Men Invented Very Unusual X-ray Guns" (Radio, Microwaves, Infrared, Visible, Ultraviolet, X-rays, Gamma rays). This mnemonic lists the radiations in order of decreasing wavelength and increasing frequency/energy.

The binary equivalent of 25 is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

The question asks to convert a decimal number (base-10) to its binary equivalent (base-2). The standard method for this is the repeated division by 2.

Step 2: Key Formula or Approach:

To convert a decimal number to binary, we repeatedly divide the decimal number by 2 and record the remainders. The process continues until the quotient becomes 0. The binary number is then obtained by reading the remainders from the bottom up.

Step 3: Detailed Explanation:

Let's convert the decimal number 25 to binary:

Divide 25 by 2: Quotient = 12, Remainder = 1

Divide 12 by 2: Quotient = 6, Remainder = 0

Divide 6 by 2: Quotient = 3, Remainder = 0

Divide 3 by 2: Quotient = 1, Remainder = 1

Divide 1 by 2: Quotient = 0, Remainder = 1

Reading the remainders from the bottom up gives us 11001.

So, \( (25)_{10} = (11001)_2 \).

Alternatively, we can express 25 as a sum of powers of 2:

The powers of 2 are ..., 32, 16, 8, 4, 2, 1.

25 can be written as:

\[ 25 = 16 + 8 + 1 \] \[ 25 = (1 \times 2^4) + (1 \times 2^3) + (0 \times 2^2) + (0 \times 2^1) + (1 \times 2^0) \]

The coefficients of the powers of 2 give the binary representation: 11001.

Step 4: Final Answer:

The binary equivalent of 25 is (11001)\(_2\). This corresponds to option (C).

Quick Tip: When converting decimal to binary, quickly check your answer by converting it back. For (11001)\(_2\), the decimal value is \(1 \cdot 2^4 + 1 \cdot 2^3 + 0 \cdot 2^2 + 0 \cdot 2^1 + 1 \cdot 2^0 = 16 + 8 + 0 + 0 + 1 = 25\). This confirms the result.

The width of diffraction fringes is .......... to the width of interference fringes.

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

This question compares the fringe widths in two key wave optics phenomena: interference (typically from a double-slit) and diffraction (typically from a single-slit). Fringe width refers to the separation between consecutive bright or dark bands in the pattern.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

Interference Fringes (e.g., Young's Double-Slit Experiment):

In the interference pattern produced by two coherent sources, all the bright and dark fringes have the same width. The fringe width (\(\beta\)) is given by the formula \(\beta = \frac{\lambda D}{d}\), where \(\lambda\) is the wavelength, \(D\) is the distance to the screen, and \(d\) is the slit separation. This width is constant across the pattern. The intensity of all bright fringes is also the same.

Diffraction Fringes (e.g., Single-Slit Diffraction):

In the diffraction pattern produced by a single slit, the fringes are not of equal width. The central bright fringe (central maximum) is much wider and more intense than the other fringes (secondary maxima). The width of the central maximum is twice the width of any of the secondary maxima. The width of the central maximum is given by \(\frac{2\lambda D}{a}\), while the width of the secondary maxima is \(\frac{\lambda D}{a}\), where \(a\) is the slit width. Also, the intensity of the secondary maxima decreases rapidly as we move away from the center.

Comparison:

Interference fringes are of equal width and intensity.

Diffraction fringes are of unequal width and intensity.

Therefore, the width of diffraction fringes is unequal when compared to each other, and fundamentally different from the uniform width of interference fringes.

Step 3: Final Answer:

The statement implies a general comparison. Since diffraction fringes are not of uniform width, while interference fringes are, the correct description is that they are unequal. Thus, option (B) is the most appropriate answer.

Quick Tip: A key visual difference to remember is that an interference pattern is a series of uniformly spaced bright bands of equal brightness, while a diffraction pattern is dominated by a very wide and bright central band, with much narrower and dimmer bands on either side.

Light year is equal to

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

A light-year is a unit of astronomical distance. It is defined as the total distance that a beam of light, moving in a vacuum, travels in one Julian year (365.25 days). It is a unit of distance, not time.

Step 2: Key Formula or Approach:

The distance can be calculated using the formula:

\[ Distance = Speed \times Time \]

Step 3: Detailed Explanation:

The values needed for the calculation are:

Speed of light in vacuum (\(c\)) \(\approx 299,792,458 m/s \approx 3 \times 10^8 m/s\)

Time (\(t\)) = 1 Julian year = 365.25 days

First, we need to convert the time from years to seconds:

\[ t = 365.25 days \times 24 \frac{hours}{day} \times 60 \frac{minutes}{hour} \times 60 \frac{seconds}{minute} \] \[ t = 31,557,600 seconds \]

Now, calculate the distance:

\[ Distance = (299,792,458 m/s) \times (31,557,600 s) \] \[ Distance \approx 9,460,730,472,580,800 m \]

In scientific notation, this is approximately:

\[ Distance \approx 9.46 \times 10^{15} m \]

Step 4: Final Answer:

One light-year is equal to approximately 9.46 x 10\(^{15}\) meters. This matches option (A).

Quick Tip: Remember the order of magnitude for common astronomical distances. A light-year is a vast distance, on the order of 10\(^{15}\) meters or 10\(^{12}\) kilometers. An Astronomical Unit (AU, the distance from Earth to the Sun) is much smaller, about 1.5 x 10\(^{11}\) meters. A parsec is larger, about 3.26 light-years.

If any ammeter is shunted, then the total resistance of the circuit

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

An ammeter is a device used to measure current in a circuit and is always connected in series. A "shunted ammeter" refers to an ammeter (or more accurately, a galvanometer) that has a low-resistance resistor, called a shunt, connected in parallel with it. This is done to extend the range of the ammeter. The question asks what effect this has on the total resistance of the circuit.

Step 2: Key Formula or Approach:

When resistors are connected in parallel, the equivalent resistance (\(R_{eq}\)) is always less than the smallest individual resistance. The formula for two resistors in parallel is:

\[ R_{eq} = \frac{R_1 R_2}{R_1 + R_2} \]

Here, \(R_1\) is the ammeter's internal resistance (\(R_A\)), and \(R_2\) is the shunt resistance (\(R_S\)). The effective resistance of the shunted ammeter is \(R'_{A} = \frac{R_A R_S}{R_A + R_S}\).

Step 3: Detailed Explanation:

1. An ammeter is placed in series in a circuit. Let the original total resistance of the circuit be \(R_{total} = R_{circuit} + R_A\), where \(R_A\) is the ammeter's resistance and \(R_{circuit}\) is the resistance of the rest of the circuit.

2. When the ammeter is shunted, a low-resistance shunt (\(R_S\)) is connected in parallel to the ammeter's internal resistance (\(R_A\)).

3. The new effective resistance of the measuring instrument, \(R'_{A}\), is the parallel combination of \(R_A\) and \(R_S\).

4. Since the equivalent resistance of a parallel combination is always smaller than the smallest of the individual resistances, and a shunt has very low resistance, we have \(R'_{A} < R_S\). And since \(R_S\) is chosen to be much smaller than \(R_A\), it is certain that \(R'_{A} < R_A\).

5. The new total resistance of the circuit becomes \(R'_{total} = R_{circuit} + R'_{A}\).

6. Since \(R'_{A} < R_A\), it follows that \(R'_{total} < R_{total}\).

Therefore, shunting an ammeter decreases its own effective resistance, which in turn decreases the total resistance of the circuit it is part of.

Step 4: Final Answer:

If an ammeter is shunted, the total resistance of the circuit decreases. Option (B) is correct.

Quick Tip: Remember the rule for parallel resistors: adding a resistor in parallel to any part of a circuit always decreases the total equivalent resistance of that part. A shunt is simply a resistor added in parallel.

The temperature coefficient of a semi-conductor is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

The temperature coefficient of resistance (\(\alpha\)) describes how the electrical resistance of a substance changes with a change in temperature. A positive coefficient means resistance increases with temperature, while a negative coefficient means resistance decreases with temperature.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

Conductors (Metals): In metals, as temperature increases, the positive ions vibrate more vigorously. This increases the frequency of collisions for the free electrons moving through the material, which in turn increases the electrical resistance. Therefore, conductors have a positive temperature coefficient of resistance.

Semi-conductors: In semi-conductors (like silicon and germanium), the electrical conductivity depends on the number of charge carriers (electrons and holes). At absolute zero, a pure semiconductor behaves like an insulator. As the temperature rises, thermal energy breaks covalent bonds, creating more electron-hole pairs. This increase in the number of charge carriers drastically increases the conductivity, and consequently, decreases the resistance.

Since the resistance of a semiconductor decreases as its temperature increases, it has a negative temperature coefficient of resistance.

Step 3: Final Answer:

The temperature coefficient of a semi-conductor is negative. Option (B) is correct.

Quick Tip: A simple way to remember this is: \textbf{Conductors}: Get "more resistive" (hotter) with heat \(\rightarrow\) \textbf{Positive} \(\alpha\). \textbf{Semi-conductors}: Get "less resistive" (more conductive) with heat \(\rightarrow\) \textbf{Negative} \(\alpha\). This behavior is a defining characteristic that distinguishes semiconductors from metals.

If T is time period and V is maximum speed of a charged particle in cyclotron, then

View Solution

Note: In a standard, non-relativistic cyclotron, the time period of revolution of a charged particle is independent of its speed and the radius of its orbit. This is the fundamental principle upon which the cyclotron operates. Therefore, none of the given proportionality options are correct. We will proceed by deriving the correct relationship.

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

A cyclotron accelerates charged particles using a constant magnetic field and an oscillating electric field. The magnetic field forces the particle to move in a circular path, and the electric field accelerates it each time it crosses the gap between the two "dee" electrodes. The question asks for the relationship between the time period of one revolution (T) and the particle's speed (V).

Step 2: Key Formula or Approach:

The magnetic force (\(F_B\)) on the charged particle provides the necessary centripetal force (\(F_c\)) to keep it in a circular path.

\[ F_B = F_c \] \[ qvB = \frac{mv^2}{r} \]

The time period (T) is the time taken to complete one full circle, which is the circumference divided by the speed.

\[ T = \frac{2\pi r}{v} \]

Step 3: Detailed Explanation:

From the force balance equation, we can find an expression for the radius \(r\):

\[ qvB = \frac{mv^2}{r} \implies r = \frac{mv}{qB} \]

Now, substitute this expression for the radius \(r\) into the time period equation:

\[ T = \frac{2\pi}{v} \left( \frac{mv}{qB} \right) \]

The speed \(v\) cancels out from the numerator and the denominator:

\[ T = \frac{2\pi m}{qB} \]

This result shows that the time period \(T\) depends only on the mass (\(m\)) and charge (\(q\)) of the particle, and the strength of the magnetic field (\(B\)). It is independent of the particle's speed (\(v\)) and the radius of its orbit (\(r\)).

Step 4: Final Answer:

The time period \(T\) is independent of the speed \(V\). The correct relationship is \(T \propto V^0\). Since this is not among the options, the question is flawed.

Quick Tip: A core principle of the cyclotron is that the revolution period is constant. This allows the use of a fixed-frequency AC voltage to accelerate the particles. Remember the formula \(T = \frac{2\pi m}{qB}\); it clearly shows no dependence on velocity or radius. This independence breaks down at very high (relativistic) speeds, which is a limitation of the classic cyclotron.

Van de Graaff generator is an electrostatic machine which produces

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

A Van de Graaff generator is a device designed to create a very large static electric potential (voltage). It operates by using a moving belt to transport electric charge from a source to a large, hollow metal sphere.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

Voltage Production: The generator accumulates a large amount of charge on the outer surface of its spherical terminal. The potential of a sphere is given by \(V = kQ/R\). By continuously transporting charge (\(Q\)) to the sphere, a very high potential difference (voltage), often in the range of millions of volts, is built up with respect to the ground. Its primary function is to produce this high voltage.

Current Production: The charge is transported mechanically by a physical belt. The rate at which charge can be moved is limited, so the resulting electric current (\(I = dQ/dt\)) is very small, typically in the microampere (\(\mu A\)) range.

Conclusion: The defining characteristic of a Van de Graaff generator is its ability to produce extremely high voltages. The current it can deliver is, by contrast, very low. Therefore, among the given choices, "Only high voltage" is the best description of its output.

Step 3: Final Answer:

A Van de Graaff generator produces a very high voltage but a very low current. Option (B) correctly identifies its main output.

Quick Tip: Think of the Van de Graaff generator as a "charge pump". It works slowly (low current) but builds up a huge amount of pressure (high voltage). It is used in applications that require high potential to accelerate particles, such as in early particle accelerators and for educational demonstrations of static electricity.

S.I. unit of permittivity is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

Permittivity (\(\epsilon\)) is a measure of how an electric field affects, and is affected by, a dielectric medium. The question asks for the SI unit of permittivity, often referring to the permittivity of free space, \(\epsilon_0\).

Step 2: Key Formula or Approach:

We can derive the unit of permittivity from Coulomb's Law, which describes the electrostatic force (\(F\)) between two point charges (\(q_1\) and \(q_2\)) separated by a distance (\(r\)).

\[ F = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \frac{q_1 q_2}{r^2} \]

Step 3: Detailed Explanation:

First, we rearrange Coulomb's Law to solve for \(\epsilon_0\):

\[ \epsilon_0 = \frac{1}{4\pi F} \frac{q_1 q_2}{r^2} \]

Now, we substitute the SI units for each physical quantity into the equation. The term \(4\pi\) is a dimensionless constant.

Unit of Force (\(F\)): Newton (N)

Unit of Charge (\(q_1, q_2\)): Coulomb (C)

Unit of Distance (\(r\)): meter (m)

Substituting these units:

\[ Unit of \epsilon_0 = \frac{1}{N} \cdot \frac{C \cdot C}{m^2} = \frac{C^2}{N \cdot m^2} \]

This unit can be written in exponent notation as:

\[ C^2 N^{-1} m^{-2} \]

Step 4: Final Answer:

The SI unit of permittivity is C\(^2\) N\(^{-1}\) m\(^{-2}\). This matches option (D).

Quick Tip: Another common unit for permittivity is Farads per meter (F/m). You can verify that this is equivalent: \(1 F = 1 C/V\) and \(1 V = 1 J/C = 1 N \cdot m/C\). Therefore, \(1 F = 1 C^2 / (N \cdot m)\). Dividing by meters gives \(1 F/m = 1 C^2 / (N \cdot m^2)\). Remembering both units (F/m and C\(^2\) N\(^{-1}\) m\(^{-2}\)) can be helpful.

The net charge on a charged capacitor is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

A capacitor is a device that stores electrical energy in an electric field. It typically consists of two conductive plates separated by an insulator (dielectric). The question asks for the net or total charge on the capacitor as a whole when it is charged.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

When a capacitor is connected to a voltage source (like a battery), the source moves electrons from one plate to the other.

- The plate that loses electrons becomes positively charged. Let's say it acquires a charge of \(+Q\).

- The plate that gains an equal number of electrons becomes negatively charged. It acquires a charge of \(-Q\).

The term "charge on a capacitor" conventionally refers to the magnitude of the charge on one of the plates (i.e., \(Q\)).

However, the *net charge* of the capacitor as a complete, isolated device is the algebraic sum of the charges on both plates.

\[ Q_{net} = (+Q) + (-Q) = 0 \]

Step 3: Final Answer:

Since one plate has a charge of \(+Q\) and the other has a charge of \(-Q\), the total net charge on the charged capacitor is zero. Therefore, option (A) is correct.

Quick Tip: Be careful with the wording. "Charge on a capacitor" usually means the magnitude of charge on the positive plate (\(Q\)). "Net charge on a capacitor" or "total charge of the capacitor" means the sum of charges on both plates, which is always zero for an isolated, charged capacitor.

The motion of an electron inside a conductor is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

This question asks to describe the overall motion of a free electron inside a conductor when an electric field is applied (i.e., when a current is flowing).

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

Free electrons in a conductor are in a state of continuous, random motion due to thermal energy, with very high speeds (thermal velocity). They frequently collide with the fixed positive ions of the metallic lattice.

When an external electric field is applied, the electrons experience an electrostatic force in the direction opposite to the field. This force accelerates the electrons. However, this acceleration lasts only for a very short time before the electron collides with a lattice ion. During the collision, the electron loses most of the energy gained from the field and its direction of motion is randomized. It then starts to accelerate again.

This process of acceleration followed by collision repeats continuously. While the instantaneous motion is a series of short accelerations, the *net effect* over a longer period is a slow, average movement in the direction opposite to the electric field. This net motion is called drift. The average velocity of this motion is called the drift velocity (\(v_d\)), which is typically very small (\(\sim 10^{-4}\) m/s) and is constant for a constant electric field.

- Uniform motion is incorrect because the instantaneous velocity is constantly changing.

- Accelerated motion is only partially correct; it describes the motion between collisions but not the overall effect.

- Retarded/Damped motion describes the effect of collisions but not the driving force from the field.

- Drifted motion is the best term to describe the overall, effective motion of the electron that gives rise to electric current.

Step 3: Final Answer:

The net or average motion of an electron inside a conductor under the influence of an electric field is a drift. Therefore, option (C) is the most accurate description.

Quick Tip: Visualize a person trying to walk through a dense, jostling crowd. They are constantly bumped and change direction (collisions), but by persistently pushing in one direction (electric field), they make slow, overall progress. This slow, net progress is the "drift". The electron's path is a chaotic series of short, curved paths, but with a net displacement over time.

The total electric flux coming out from stationary unit positive charge in air is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

This question requires the application of Gauss's Law in electrostatics. Gauss's Law relates the total electric flux (\(\Phi_E\)) through any closed surface (called a Gaussian surface) to the net electric charge (\(Q_{enc}\)) enclosed by that surface.

Step 2: Key Formula or Approach:

Gauss's Law is stated mathematically as:

\[ \Phi_E = \oint \vec{E} \cdot d\vec{A} = \frac{Q_{enc}}{\epsilon} \]

Where:

\(\Phi_E\) is the total electric flux.

\(Q_{enc}\) is the total charge enclosed within the surface.

\(\epsilon\) is the permittivity of the medium. For air or vacuum, we use the permittivity of free space, \(\epsilon_0\).

Step 3: Detailed Explanation:

According to the problem statement:

- The charge is a "unit positive charge", which means \(Q_{enc} = +1\) C.

- The medium is "air", so we use the permittivity \(\epsilon_0\).

Substituting these values into Gauss's Law:

\[ \Phi_E = \frac{+1}{\epsilon_0} \]

This can be written using a negative exponent as:

\[ \Phi_E = (\epsilon_0)^{-1} \]

Step 4: Final Answer:

The total electric flux is \((\epsilon_0)^{-1}\). This corresponds to option (B).

Quick Tip: Gauss's Law is a powerful tool for calculating electric flux. Remember that the flux depends only on the enclosed charge, not on the shape or size of the Gaussian surface. For a point charge, the flux is the same through a small sphere around it as it is through a large, irregularly shaped surface enclosing it.

The force, acting on per unit charge is called

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

This question asks for the definition of a fundamental quantity in electrostatics. We need to identify the physical quantity that is defined as the electrostatic force experienced by a charge divided by the magnitude of that charge.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

Let's analyze the definitions of the given options:

- Electric current is the rate of flow of electric charge (\(I = dQ/dt\)). It is not force per unit charge.

- Electric potential at a point is the work done in moving a unit positive charge from a reference point (usually infinity) to that point (\(V = W/q\)). It is energy per unit charge, not force per unit charge.

- Electric field (or electric field intensity, \(\vec{E}\)) at a point is defined as the electrostatic force (\(\vec{F}\)) experienced by a small positive test charge (\(q_0\)) placed at that point, divided by the magnitude of the test charge.

\[ \vec{E} = \frac{\vec{F}}{q_0} \]

This exactly matches the description "force, acting on per unit charge".

- Electric space is not a standard term in physics for a physical quantity.

Step 3: Final Answer:

The force per unit charge is the definition of the electric field. Therefore, option (C) is correct.

Quick Tip: Remember the key "per unit charge" definitions: \textbf{Force} per unit charge = \textbf{Electric Field} (\(E=F/q\)). \textbf{Potential Energy} per unit charge = \textbf{Electric Potential} (\(V=U/q\)). This distinction is crucial for solving problems in electrostatics.

Quantisation of charge indicates that

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

The principle of "quantisation of charge" is a fundamental property of electric charge. It states that electric charge is not continuous but exists in discrete packets.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

The principle of quantisation of charge states that the total charge (\(Q\)) on any object is always an integer multiple of a basic unit of charge, denoted by \(e\). This basic unit is the magnitude of the charge of a single electron or proton (\(e \approx 1.602 \times 10^{-19}\) C).

The formula is: \(Q = ne\), where \(n\) is an integer (\(n = 0, \pm 1, \pm 2, \ldots\)).

Let's evaluate the given options based on this principle:

(A) Charge, which is a fraction of charge on an electron, is not possible: This is a direct consequence of the rule \(Q = ne\). Since \(n\) must be an integer, it is impossible for an isolated object to have a charge of, for example, 0.5\(e\) or 1.7\(e\). This statement accurately describes quantisation.

(B) A charge cannot be destroyed: This describes the law of conservation of charge, which is a different principle.

(C) Charge exists on particles: This is a true statement, but it is not the meaning of quantisation.

(D) There exists a minimum permissible charge on a particle: This is also a consequence of quantisation (the minimum non-zero charge is \(e\)), but option (A) is a more complete and precise statement of the principle. It explains *why* there is a minimum charge and also rules out all non-integer multiples, not just those below the minimum.

Step 3: Final Answer:

The most accurate and comprehensive description of the quantisation of charge among the choices is that charge cannot exist as a fraction of the elementary charge \(e\). Therefore, option (A) is the best answer.

Quick Tip: Distinguish between the three fundamental properties of charge: 1. \textbf{Quantisation}: Charge comes in integer multiples of \(e\). (\(Q=ne\)). 2. \textbf{Conservation}: The total charge of an isolated system remains constant. 3. \textbf{Additivity}: The total charge of a system is the algebraic sum of individual charges.

Electric field lines provide information about

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

Electric field lines are a visual tool used to represent electric fields. They have several properties that convey information about the field and the charges creating it.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

Let's examine what information can be obtained from electric field lines:

(A) Field strength: The density of the electric field lines (how close they are to one another) in a region is proportional to the magnitude, or strength, of the electric field in that region. Where the lines are close together, the field is strong; where they are far apart, the field is weak.

(B) Direction: The tangent to an electric field line at any point gives the direction of the electric field vector \(\vec{E}\) at that point. The arrowhead on the line indicates the direction of the force that would be exerted on a positive test charge.

(C) Nature of charge: Electric field lines originate from positive charges and terminate on negative charges (or extend to infinity). By observing the pattern of where lines begin and end, we can determine the location and nature (positive or negative) of the source charges.

Since electric field lines provide information about field strength, direction, and the nature of the charge, all the given options are correct.

Step 3: Final Answer:

Electric field lines provide information about all the listed properties. Therefore, option (D) is the correct answer.

Quick Tip: Remember these key rules for electric field lines: 1. They point from positive to negative. 2. They never cross each other. 3. Their density indicates field strength. 4. They are perpendicular to the surface of conductors in electrostatic equilibrium.

Nickel is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

Materials are classified based on their behavior in an external magnetic field. The main categories are diamagnetic, paramagnetic, and ferromagnetic.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

- Diamagnetic materials are weakly repelled by a magnetic field. They have a magnetic permeability slightly less than that of a vacuum. Examples include water, copper, and bismuth.

- Paramagnetic materials are weakly attracted to a magnetic field. They have a magnetic permeability slightly greater than that of a vacuum. Examples include aluminum, platinum, and oxygen.

- Ferromagnetic materials are very strongly attracted to a magnetic field and can be permanently magnetized. They have a very high magnetic permeability. The atoms in these materials have magnetic moments that align in large regions called domains.

Nickel (Ni) is one of the three common elements, along with Iron (Fe) and Cobalt (Co), that exhibit ferromagnetism at room temperature.

Step 3: Final Answer:

Nickel is a ferromagnetic material. Therefore, option (C) is correct.

Quick Tip: Remember the "big three" ferromagnetic elements: Iron (Fe), Cobalt (Co), and Nickel (Ni). These are the most common examples asked in exams.

The angle between magnetic meridian and geographical meridian is called

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

This question asks for the definition of one of the elements of Earth's magnetic field, which are used to describe the field at any point on the Earth's surface.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

Let's define the key terms:

- Geographical Meridian: An imaginary vertical plane passing through a point on the Earth's surface and the Earth's axis of rotation (i.e., passing through the geographic North and South poles). It defines the direction of true north.

- Magnetic Meridian: An imaginary vertical plane at a point on the Earth's surface which contains the direction of the horizontal component of the Earth's magnetic field. A freely suspended compass needle aligns itself in this plane. It defines the direction of magnetic north.

- Angle of Declination (\(\theta\)): The angle between the geographical meridian and the magnetic meridian at a place. It is the angle by which a compass needle deviates from true north.

- Angle of Dip (\(\delta\)): The angle between the direction of the Earth's total magnetic field and the horizontal direction in the magnetic meridian.

The question asks for the angle between the magnetic meridian and the geographical meridian, which is the definition of the angle of declination.

Step 3: Final Answer:

The angle between the magnetic meridian and geographical meridian is called declination. Therefore, option (B) is correct.

Quick Tip: Think of it this way: \textbf{De}clination tells you how much to \textbf{de}viate your compass from true north. \textbf{Dip} tells you how much the magnetic field vector \textbf{dip}s below the horizontal.

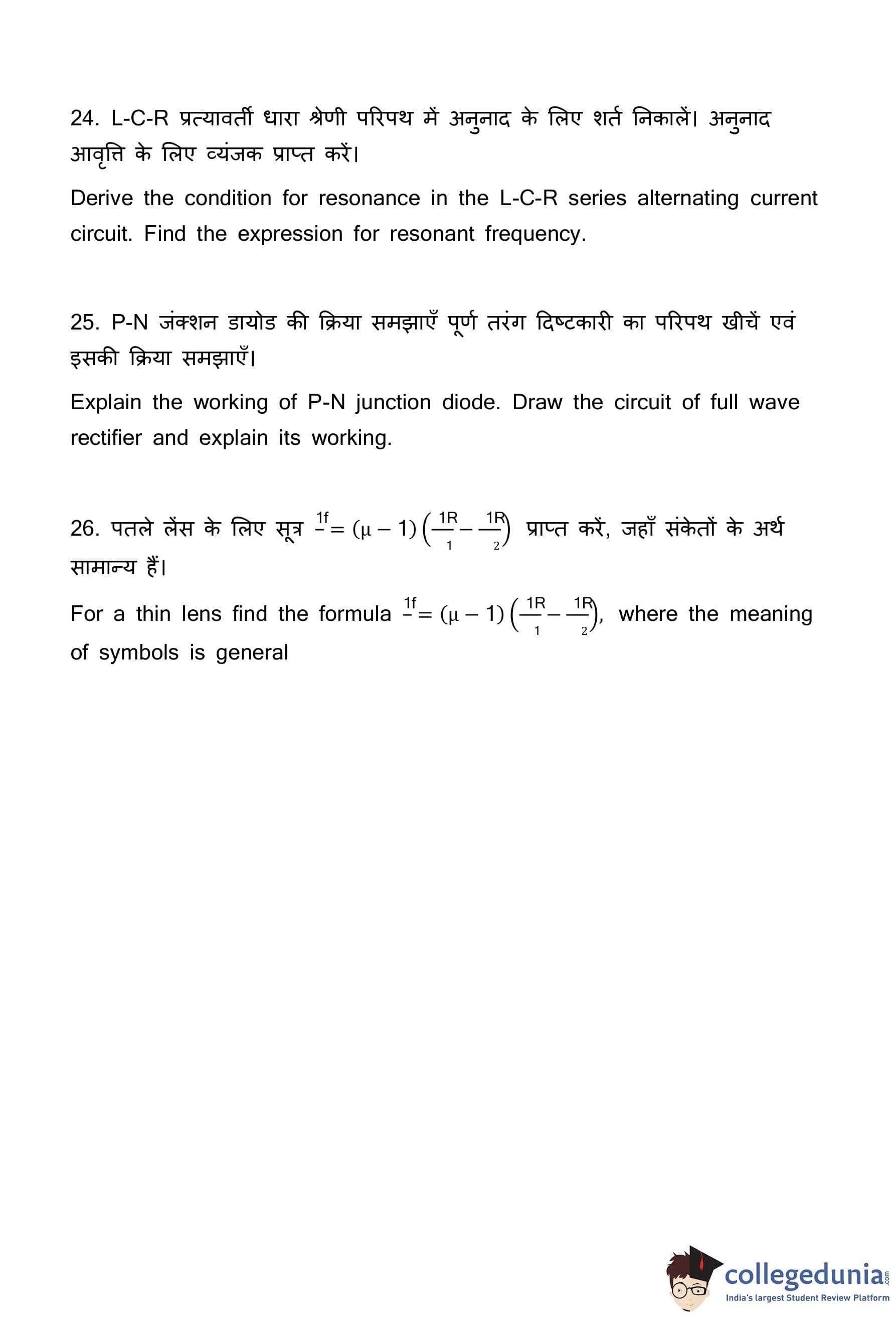

The radius of curvature of each surface of a biconvex lens is 20 cm and the refractive index of the material of the lens is 1.5. The focal length of the lens is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

The problem requires finding the focal length of a biconvex lens given its radii of curvature and refractive index. This can be solved using the Lens Maker's Formula.

Step 2: Key Formula or Approach:

The Lens Maker's Formula is: \[ \frac{1}{f} = (\mu - 1) \left( \frac{1}{R_1} - \frac{1}{R_2} \right) \]

where: \(f\) = focal length of the lens \(\mu\) = refractive index of the lens material with respect to the surrounding medium (air, in this case) \(R_1\) = radius of curvature of the first surface (where light enters) \(R_2\) = radius of curvature of the second surface

Step 3: Detailed Explanation:

Given data:

- Type of lens: Biconvex

- Refractive index, \(\mu = 1.5\)

- Radius of curvature of each surface = 20 cm.

We must apply the Cartesian sign convention. Assume light travels from left to right.

- For the first surface (left), it is convex towards the incident light. Its center of curvature is on the right side. Thus, \(R_1 = +20\) cm.

- For the second surface (right), it is also convex, but its center of curvature is on the left side. Thus, \(R_2 = -20\) cm.

Now, substitute these values into the Lens Maker's Formula: \[ \frac{1}{f} = (1.5 - 1) \left( \frac{1}{+20} - \frac{1}{-20} \right) \] \[ \frac{1}{f} = (0.5) \left( \frac{1}{20} + \frac{1}{20} \right) \] \[ \frac{1}{f} = (0.5) \left( \frac{2}{20} \right) \] \[ \frac{1}{f} = \left(\frac{1}{2}\right) \left( \frac{1}{10} \right) \] \[ \frac{1}{f} = \frac{1}{20} \]

Therefore, the focal length is: \[ f = 20 cm \]

Step 4: Final Answer:

The focal length of the lens is 20 cm. This corresponds to option (C).

Quick Tip: For a symmetric biconvex lens (\(R_1 = R, R_2 = -R\)) made of a material with \(\mu=1.5\), the focal length is simply equal to the radius of curvature (\(f=R\)). This is a useful shortcut to remember for quick checks.

Which physical quantity will be the same for an electron and a photon of the same wavelength?

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

This question deals with the wave-particle duality, specifically the de Broglie wavelength for matter particles (like electrons) and the properties of photons. We need to compare different physical quantities for an electron and a photon that share the same wavelength \(\lambda\).

Step 2: Key Formula or Approach:

The key relationship connecting wavelength and momentum is the de Broglie relation, which applies to both matter particles and photons.

\[ p = \frac{h}{\lambda} \]

where \(p\) is momentum, \(h\) is Planck's constant, and \(\lambda\) is the wavelength.

Step 3: Detailed Explanation:

Let's analyze each quantity for an electron and a photon with the same wavelength \(\lambda\).

(A) Velocity: A photon always travels at the speed of light, \(c\). An electron has rest mass, so its speed \(v\) must be less than \(c\). Therefore, their velocities are not the same.

(B) Energy:

- The energy of a photon is given by \(E_{photon} = hf = \frac{hc}{\lambda}\).

- The kinetic energy of a non-relativistic electron is \(E_{electron} = \frac{p^2}{2m} = \frac{(h/\lambda)^2}{2m} = \frac{h^2}{2m\lambda^2}\).

Since the formulas are different, their energies will not be the same.

(C) Momentum:

- The momentum of a photon is given by \(p_{photon} = \frac{h}{\lambda}\).

- The de Broglie momentum of an electron is given by \(p_{electron} = \frac{h}{\lambda}\).

Since both \(h\) and \(\lambda\) are the same for the electron and the photon, their momenta must be equal.

(D) Angular momentum: This quantity is not inherently defined just by wavelength and would depend on other conditions (like orbital motion), so it is not guaranteed to be the same.

Step 4: Final Answer:

For the same wavelength \(\lambda\), both the electron and the photon will have the same momentum, \(p = h/\lambda\). Thus, option (C) is correct.

Quick Tip: The de Broglie relation \(p = h/\lambda\) is universal. It's the bridge that connects the particle property (momentum, \(p\)) to the wave property (wavelength, \(\lambda\)) for any quantum entity, whether it's a photon or a particle with mass.

The function of moderator in nuclear reactor is to

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

A nuclear reactor generates energy through a controlled nuclear chain reaction. In reactors using uranium-235, the fission process is most efficiently initiated by slow-moving neutrons, often called thermal neutrons.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

The fission of a uranium nucleus releases high-energy, fast-moving neutrons.

These fast neutrons are not very effective at causing fission in other uranium nuclei, as the probability of capture and fission is much lower at high energies.

To sustain the chain reaction efficiently, these fast neutrons must be slowed down to thermal energies.

The material used for this purpose is called a moderator.

The moderator consists of light nuclei (like hydrogen in water or carbon in graphite) that slow down the neutrons through a series of elastic collisions without absorbing them.

Therefore, the primary function of a moderator is to reduce the kinetic energy, or slow the speed, of fast neutrons.

Step 3: Final Answer:

Based on the explanation, the function of a moderator is to slow the speed of neutrons to sustain the nuclear chain reaction. Thus, option (A) is correct.

Quick Tip: Commonly used moderators in nuclear reactors are ordinary water (H\(_2\)O), heavy water (D\(_2\)O), and graphite. Remember that the moderator's job is to 'moderate' or slow down the neutron speed, not to absorb them (that's the job of control rods, which are made of neutron-absorbing materials like Cadmium or Boron).

The impurity element used for p-type semiconductor is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

Semiconductors like Silicon (Si) and Germanium (Ge) belong to Group 14 of the periodic table and are tetravalent (have 4 valence electrons). Their electrical conductivity can be significantly increased by adding a small amount of a suitable impurity, a process called doping. This creates extrinsic semiconductors.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

p-type semiconductor: This type is formed when a tetravalent semiconductor (like Si) is doped with a trivalent impurity (an element with 3 valence electrons, from Group 13). The trivalent impurity atom replaces a silicon atom in the crystal lattice. It forms covalent bonds with three neighboring Si atoms, but there is a deficiency of one electron to bond with the fourth Si atom. This deficiency is called a "hole," which acts as a positive charge carrier.

n-type semiconductor: This type is formed by doping with a pentavalent impurity (an element with 5 valence electrons, from Group 15). The fifth electron is loosely bound and can easily become a free electron, acting as a negative charge carrier.

Step 3: Analyzing the Options:

(A) Boron (B): Belongs to Group 13, it is trivalent. Doping with Boron creates holes, resulting in a p-type semiconductor.

(B) Bismuth (Bi): Belongs to Group 15, it is pentavalent. Used for n-type doping.

(C) Arsenic (As): Belongs to Group 15, it is pentavalent. Used for n-type doping.

(D) Phosphorus (P): Belongs to Group 15, it is pentavalent. Used for n-type doping.

Step 4: Final Answer:

To create a p-type semiconductor, a trivalent impurity is required. Among the given options, only Boron is a trivalent element. Therefore, option (A) is correct.

Quick Tip: A helpful mnemonic to remember dopants is: \textbf{B-Al-Ga-In-Tl} (Elements of Group 13) are trivalent impurities that create \textbf{p-type} semiconductors (they are acceptor atoms). \textbf{P-As-Sb-Bi} (Elements of Group 15) are pentavalent impurities that create \textbf{n-type} semiconductors (they are donor atoms).

Diode is used as

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

A semiconductor diode (typically a p-n junction diode) is a two-terminal electronic component whose fundamental characteristic is that it allows electric current to flow easily in one direction (forward bias) while severely restricting it in the opposite direction (reverse bias).

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

This property of allowing unidirectional current flow is the key principle behind rectification.

Rectification is the process of converting alternating current (AC), which periodically reverses its direction, into direct current (DC), which flows in only one direction.

A diode, when placed in an AC circuit, acts like a one-way electrical valve. It allows either the positive or negative half-cycles of the AC waveform to pass through while blocking the other half. This converts the AC into a pulsating DC.

Step 3: Analyzing the Options:

(A) Amplifier: A device that increases the amplitude of an electrical signal. This is the primary function of a transistor.

(B) Oscillator: A circuit that produces a continuous, repeated, alternating waveform without any input. Transistors or op-amps are typically used.

(C) Modulator: A device used in communications to superimpose a message signal onto a high-frequency carrier wave.

(D) Rectifier: A device that converts AC to DC. This is the most fundamental application of a diode.

Step 4: Final Answer:

The primary and most common application of a diode is to function as a rectifier due to its ability to conduct current in only one direction. Therefore, option (D) is correct.

Quick Tip: Think of the arrow in the diode's circuit symbol. The arrow points in the direction of conventional current flow (from the p-side/anode to the n-side/cathode). This visual cue helps to remember its function as a one-way gate for current, which is the essence of rectification.

Three capacitors of capacitance 6 µF are available. The minimum and maximum capacitances obtained are

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

To obtain the maximum equivalent capacitance from a set of capacitors, they should be connected in parallel. To obtain the minimum equivalent capacitance, they should be connected in series.

Step 2: Key Formula or Approach:

Given three capacitors, each with capacitance \( C = 6 \, \mu F \).

For Parallel Combination (Maximum Capacitance):

The equivalent capacitance \(C_{p}\) is the sum of individual capacitances. \[ C_{max} = C_1 + C_2 + C_3 \]

For Series Combination (Minimum Capacitance):

The reciprocal of the equivalent capacitance \(C_{s}\) is the sum of the reciprocals of individual capacitances. \[ \frac{1}{C_{min}} = \frac{1}{C_1} + \frac{1}{C_2} + \frac{1}{C_3} \]

Step 3: Detailed Explanation:

Calculation for Maximum Capacitance (Parallel):

Connect all three 6 µF capacitors in parallel. \[ C_{max} = 6 \, \mu F + 6 \, \mu F + 6 \, \mu F = 18 \, \mu F \]

Calculation for Minimum Capacitance (Series):

Connect all three 6 µF capacitors in series. \[ \frac{1}{C_{min}} = \frac{1}{6} + \frac{1}{6} + \frac{1}{6} = \frac{1+1+1}{6} = \frac{3}{6} = \frac{1}{2} \]

To find \(C_{min}\), we take the reciprocal: \[ C_{min} = 2 \, \mu F \]

Step 4: Final Answer:

The minimum capacitance obtained is 2 µF, and the maximum capacitance obtained is 18 µF. Therefore, option (C) is the correct choice.

Quick Tip: Remember that the rules for combining capacitors are the opposite of those for resistors. Capacitors in \textbf{parallel} add up like resistors in \textbf{series} (\(C_{eq} = C_1 + C_2 + \dots\)). Capacitors in \textbf{series} use the reciprocal formula, like resistors in \textbf{parallel} (\(1/C_{eq} = 1/C_1 + 1/C_2 + \dots\)).

The root mean square (r.m.s) value of alternating current equation I = 60 sin 100 πt is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

The root mean square (r.m.s) value of an alternating current (AC) represents the effective DC value that would deliver the same average power to a resistor. For a sinusoidal current, it is directly related to its peak (maximum) value.

Step 2: Key Formula or Approach:

The general equation for a sinusoidal AC is given by: \[ I(t) = I_0 \sin(\omega t) \]

where \(I_0\) is the peak amplitude or maximum current.

The r.m.s value (\(I_{rms}\)) is related to the peak current by the formula: \[ I_{rms} = \frac{I_0}{\sqrt{2}} \]

Step 3: Detailed Explanation:

The given equation for the current is \(I = 60 \sin(100 \pi t)\).

By comparing this with the standard form \(I = I_0 \sin(\omega t)\), we can identify the peak current: \[ I_0 = 60 \, A \]

Now, we apply the formula for the r.m.s value: \[ I_{rms} = \frac{I_0}{\sqrt{2}} = \frac{60}{\sqrt{2}} \]

To simplify this expression, we rationalize the denominator by multiplying the numerator and denominator by \(\sqrt{2}\): \[ I_{rms} = \frac{60}{\sqrt{2}} \times \frac{\sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{2}} = \frac{60\sqrt{2}}{2} = 30\sqrt{2} \, A \]

Step 4: Final Answer:

The calculated r.m.s value is \(30\sqrt{2}\) A, which is approximately \(42.4\) A. This value does not match any of the given options. There appears to be an error in the question or the options. In such cases in an exam, it is common that there was a typo in the question. For instance, if the equation had been \(I = 30\sqrt{2} \sin(100 \pi t)\), then \(I_{rms}\) would be \(\frac{30\sqrt{2}}{\sqrt{2}} = 30\) A, matching option (B). Given the choices, it's highly probable this was the intended question. However, based strictly on the question provided, none of the options is correct.

Quick Tip: The RMS value for a sinusoidal waveform is always the peak value divided by \(\sqrt{2}\) (approximately 0.707 times the peak value). Conversely, the peak value is \(\sqrt{2}\) times the RMS value. This is a crucial relationship in AC circuit analysis. When your answer doesn't match, double-check your calculation and then look for plausible typos in the question.

The impedance of L-R circuit is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

Impedance (\(Z\)) is the total opposition that a circuit presents to the flow of alternating current. In a series L-R circuit, it arises from two sources: the resistance (\(R\)) of the resistor and the inductive reactance (\(X_L\)) of the inductor. These two quantities do not add arithmetically because the voltage across the resistor is in phase with the current, while the voltage across the inductor leads the current by 90 degrees.

Step 2: Key Formula or Approach:

The resistance is \(R\).

The inductive reactance is given by \(X_L = \omega L\), where \(\omega\) is the angular frequency of the AC supply.

Since \(R\) and \(X_L\) are out of phase by 90°, they are combined as vectors (or phasors) using the Pythagorean theorem. This can be visualized using an impedance triangle where R is the adjacent side, \(X_L\) is the opposite side, and Z is the hypotenuse. \[ Z = \sqrt{R^2 + X_L^2} \]

Step 3: Detailed Explanation:

Substitute the expression for inductive reactance (\(X_L = \omega L\)) into the general formula for impedance: \[ Z = \sqrt{R^2 + (\omega L)^2} \]

This simplifies to: \[ Z = \sqrt{R^2 + \omega^2 L^2} \]

Step 4: Final Answer:

Comparing the derived expression with the given options, we see that option (D) correctly represents the impedance of a series L-R circuit.

Quick Tip: For any series RLC circuit, the impedance is \(Z = \sqrt{R^2 + (X_L - X_C)^2}\). For an L-R circuit, there is no capacitor, so \(X_C = 0\), which simplifies the formula to \(Z = \sqrt{R^2 + X_L^2}\). For an R-C circuit, \(X_L = 0\), so \(Z = \sqrt{R^2 + (-X_C)^2} = \sqrt{R^2 + X_C^2}\).

The radius of a circular current loop is made double and the current is made half. The magnetic moment of the loop will become

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

The magnetic dipole moment (\(\mu\)) of a current loop is a vector quantity that measures the strength and orientation of the magnetic field produced by the loop. Its magnitude is the product of the current flowing in the loop and the area enclosed by the loop.

Step 2: Key Formula or Approach:

The formula for the magnetic moment (\(\mu\)) of a current loop is: \[ \mu = I \cdot A \]

where \(I\) is the current and \(A\) is the area of the loop.

For a circular loop of radius \(r\), the area is \(A = \pi r^2\).

Therefore, the formula becomes: \[ \mu = I \pi r^2 \]

Step 3: Detailed Explanation:

Let the initial conditions be:

Initial current = \(I\)

Initial radius = \(r\)

So, the initial magnetic moment is \(\mu_{initial} = I \pi r^2\).

Now, the conditions are changed as follows:

New current, \(I' = \frac{I}{2}\) (halved)

New radius, \(r' = 2r\) (doubled)

Let's calculate the new magnetic moment (\(\mu_{new}\)) with these new values: \[ \mu_{new} = I' \cdot \pi (r')^2 \]

Substitute the expressions for \(I'\) and \(r'\): \[ \mu_{new} = \left(\frac{I}{2}\right) \cdot \pi (2r)^2 \] \[ \mu_{new} = \left(\frac{I}{2}\right) \cdot \pi (4r^2) \]

Rearrange the terms: \[ \mu_{new} = \left(\frac{4}{2}\right) \cdot (I \pi r^2) \] \[ \mu_{new} = 2 \cdot (I \pi r^2) \]

Since \(\mu_{initial} = I \pi r^2\), we can write: \[ \mu_{new} = 2 \cdot \mu_{initial} \]

Step 4: Final Answer:

The new magnetic moment is twice the initial magnetic moment. Therefore, the magnetic moment of the loop will be doubled. Option (B) is correct.

Quick Tip: For problems involving proportional changes, you can analyze the dependencies. Here, \(\mu \propto I\) and \(\mu \propto r^2\). So, \(\mu \propto I r^2\). The new moment \(\mu'\) will be proportional to \(I' (r')^2 = (\frac{1}{2}I)(2r)^2 = (\frac{1}{2})(4)Ir^2 = 2Ir^2\). Thus, the new moment is twice the original.

The self-inductance of a choke coil is 5 henry. The current through it is increasing at a rate of 2 AS\(^{-1}\). The self-induced emf in the choke coil will be

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

According to Faraday's law of induction and Lenz's law, when the current through an inductor changes, a back electromotive force (emf) is induced across it. This self-induced emf opposes the change in current.

Step 2: Key Formula or Approach:

The self-induced emf (\(\epsilon\)) in an inductor is given by the formula: \[ \epsilon = -L \frac{dI}{dt} \]

where:

\(L\) is the self-inductance of the coil.

\(\frac{dI}{dt}\) is the rate of change of current.

The negative sign indicates that the induced emf opposes the change in current (Lenz's Law).

Step 3: Detailed Explanation:

Given values are:

Self-inductance, \(L = 5\) H.

Rate of increase of current, \(\frac{dI}{dt} = 2\) A/s.

Substitute these values into the formula: \[ \epsilon = - (5 \, H) \times (2 \, A/s) \] \[ \epsilon = -10 \, V \]

Step 4: Final Answer:

The self-induced emf in the choke coil is -10 V. The negative sign signifies that the emf is induced in a direction that opposes the increase in current. Therefore, option (C) is the correct answer.

Quick Tip: Remember Lenz's law is represented by the negative sign in the formula \(\epsilon = -L \frac{dI}{dt}\). If the question asks for the magnitude of the induced emf, the answer would be 10 V. However, since -10 V is an option, it is the more precise answer as it includes the direction (polarity) of the emf.

Magnetic moment of the earth is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

The Earth behaves like a large magnet with a magnetic field extending into space. This magnetic field is generated by the motion of molten iron alloys in its outer core. The strength of this magnetic field is quantified by its magnetic dipole moment. This is a factual, standard value in physics.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

The magnetic moment of the Earth has been measured through various geophysical methods. The currently accepted approximate value for the Earth's magnetic dipole moment is about \(8.0 \times 10^{22}\) Joules per Tesla (J T\(^{-1}\)).

The unit J T\(^{-1}\) is equivalent to Ampere-meter squared (A m\(^2\)), which is the standard SI unit for magnetic moment.

Let's check the options:

(A), (B), and (C) present values that are drastically different in magnitude from the known value.

(D) provides the correct order of magnitude and the standard value for the Earth's magnetic moment.

Step 3: Final Answer:

The accepted value for the magnetic moment of the Earth is approximately \(8.0 \times 10^{22}\) J T\(^{-1}\). Therefore, option (D) is correct.

Quick Tip: Some physical constants and standard values, like the charge of an electron, Planck's constant, and the magnetic moment of the Earth, are often asked in exams. It's beneficial to memorize the approximate values and their orders of magnitude.

The phase difference between electric wave and magnetic wave in the electromagnetic wave is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

An electromagnetic (EM) wave consists of oscillating electric field (\(\vec{E}\)) and magnetic field (\(\vec{B}\)) vectors. These fields are perpendicular to each other and also perpendicular to the direction of wave propagation. A key characteristic of EM waves is the relationship between the phases of these two fields.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

According to Maxwell's equations for EM waves in a vacuum or free space, the electric and magnetic fields are always in phase. This means that they reach their maximum values at the same time and at the same point in space. Similarly, they both pass through zero and reach their minimum values simultaneously.

If the electric field is described by \(E = E_0 \sin(kx - \omega t)\), the magnetic field will be described by \(B = B_0 \sin(kx - \omega t)\).

The phase for both waves is the term \((kx - \omega t)\). Since the phase term is identical for both, the phase difference between them is zero.

Step 3: Final Answer:

The electric and magnetic fields in an electromagnetic wave oscillate in phase with each other. Therefore, the phase difference between them is zero. Option (D) is correct.

Quick Tip: Remember the key properties of EM waves: 1. \(\vec{E}\) and \(\vec{B}\) are mutually perpendicular. 2. The direction of propagation is given by \(\vec{E} \times \vec{B}\). 3. \(\vec{E}\) and \(\vec{B}\) are always in phase (phase difference is zero). 4. The ratio of their magnitudes is constant: \(E/B = c\) (speed of light).

When the distance between source of light and screen is increased, then fringe width

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

This question relates to the interference of light, typically observed in an experiment like Young's Double-Slit Experiment (YDSE). Fringe width is the distance between two consecutive bright or dark fringes on the screen.

Step 2: Key Formula or Approach:

The formula for the fringe width (\(\beta\)) in a double-slit interference pattern is: \[ \beta = \frac{\lambda D}{d} \]

where:

\(\lambda\) is the wavelength of the light used.

\(D\) is the distance between the slits (which act as the coherent sources) and the screen.

\(d\) is the distance between the two slits.

Step 3: Detailed Explanation:

The question states that the distance between the source of light (slits) and the screen is increased. This corresponds to an increase in the value of \(D\).

From the formula \(\beta = \frac{\lambda D}{d}\), we can see that the fringe width \(\beta\) is directly proportional to the distance \(D\), assuming \(\lambda\) and \(d\) are constant. \[ \beta \propto D \]

Therefore, if \(D\) increases, the fringe width \(\beta\) will also increase. This means the bright and dark fringes on the screen will become more spread out.

Step 4: Final Answer:

Since the fringe width is directly proportional to the distance between the source and the screen, increasing this distance will cause the fringe width to increase. Option (A) is correct.

Quick Tip: To get wide, easily visible fringes, you should increase the screen distance (\(D\)) and use light with a longer wavelength (\(\lambda\)), while keeping the slit separation (\(d\)) small. This relationship \(\beta = \lambda D/d\) is fundamental to wave optics problems.

The unit of radioactivity is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

Radioactivity (or simply activity) of a radioactive sample is defined as the rate at which the nuclei of its constituent atoms decay. It is a measure of the number of disintegrations per unit time.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

Let's analyze the units given in the options:

(A) MeV (Mega-electron Volt): This is a unit of energy, commonly used in nuclear physics. \(1 \, MeV = 1.602 \times 10^{-13}\) Joules. It is not a unit of decay rate.

(B) Curie (Ci): This is a traditional unit of radioactivity. It is defined as \(1 \, Ci = 3.7 \times 10^{10}\) decays per second. It is a valid unit for radioactivity.

(C) a.m.u. (atomic mass unit): This is a unit of mass, used for atomic and subatomic particles. \(1 \, a.m.u. \approx 1.66 \times 10^{-27}\) kg. It is not a unit of decay rate.

(D) Joule (J): This is the SI unit of energy or work. It is not a unit of decay rate.

The SI unit of radioactivity is the Becquerel (Bq), where 1 Bq = 1 decay per second. The Curie is a larger, non-SI unit that is still widely used.

Step 3: Final Answer:

Among the given options, only the curie is a unit used to measure radioactivity. Therefore, option (B) is correct.

Quick Tip: Be careful to distinguish between units of energy (Joule, eV, MeV) and units of activity/radioactivity (Becquerel, Curie). Activity measures the 'how fast' of decay, while energy measures the 'how much' energy is released per decay.

Which of the following has the highest penetrating power?

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

Penetrating power is the ability of a form of radiation to pass through matter. The more a particle or ray interacts with the atoms of the material it passes through, the more quickly it loses its energy and the lower its penetrating power.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

Let's compare the penetrating power of the given radiations:

(A) \(\alpha\)-rays (Alpha particles): These are helium nuclei (\(^{4}_{2}He\)). They have a large mass and a double positive charge (+2e). Due to their strong charge and large size, they interact very strongly with matter through ionization. They lose their energy over a very short distance and have the \textit{lowest penetrating power. They can be stopped by a sheet of paper or even the outer layer of skin.

(B) \(\beta\)-rays (Beta particles): These are high-speed electrons or positrons. They are much lighter than alpha particles and have a single charge (-e or +e). They interact less strongly with matter than alpha particles, so they can penetrate further. They have a \textit{medium penetrating power and can be stopped by a few millimeters of aluminum.

(C) \(\gamma\)-rays (Gamma rays): These are high-energy photons (electromagnetic radiation). They have no mass and no charge. Because they are uncharged, they do not interact strongly via electrostatic forces and penetrate deeply into matter. They have the \textit{highest penetrating power and require thick layers of dense materials like lead or concrete to be significantly attenuated.

(D) Cathode rays: These are streams of electrons, essentially the same as beta particles but typically with lower energies found in cathode ray tubes. Their penetrating power is less than that of gamma rays and is comparable to beta particles.

Step 3: Final Answer:

Comparing the four options, gamma rays have the least interaction with matter due to their lack of charge and mass, giving them the highest penetrating power. Therefore, option (C) is correct.

Quick Tip: A simple way to remember the order of penetrating power is: \(\gamma > \beta > \alpha\). The opposite is true for ionizing power: \(\alpha > \beta > \gamma\). The more ionizing a particle is, the less penetrating it is.

Which range of frequency is used in TV transmission?

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

TV transmission requires a large bandwidth to carry both video (picture) and audio (sound) information. This necessitates the use of high-frequency carrier waves. The electromagnetic spectrum is divided into bands, and specific ranges are allocated for different communication purposes.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

Let's examine the frequency ranges given:

(A) 30 Hz - 300 Hz: This is the Extremely Low Frequency (ELF) range. These frequencies are in the audible range for humans and have very long wavelengths. They are not suitable for carrying the vast amount of information in a TV signal.

(B) 30 kHz - 300 kHz: This is the Low Frequency (LF) band. It is used for applications like AM radio broadcasting and navigation systems. The bandwidth is still insufficient for television.

(C) 30 MHz - 300 MHz: This is the Very High Frequency (VHF) band. This range provides sufficient bandwidth for TV signals and is historically the primary band used for terrestrial television broadcasting (e.g., channels 2-13 in North America).

(D) 30 GHz - 300 GHz: This is the Extremely High Frequency (EHF) band, also known as millimeter waves. This range is used for high-speed microwave data links, radio astronomy, and satellite communication, but not typically for conventional terrestrial TV broadcasting.

In addition to the VHF band, the Ultra High Frequency (UHF) band (300 MHz - 3 GHz) is also used for TV transmission. However, the range given in option (C) is the correct and standard band used for television.

Step 3: Final Answer:

The frequency range corresponding to the Very High Frequency (VHF) band, which is 30 MHz - 300 MHz, is used for TV transmission. Therefore, option (C) is correct.

Quick Tip: Remember the general order of the radio spectrum for communication: AM Radio (kHz), FM Radio \& TV (MHz), and Satellite \& Wi-Fi (GHz). This helps in quickly eliminating incorrect options in questions related to frequency bands.

The dispersive power of a prism depends on

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

Dispersive power (\(\omega\)) is a property of the material of a prism that quantifies its ability to separate white light into its constituent colors (dispersion). It is defined as the ratio of the angular dispersion (the difference in deviation angles for two extreme colors, typically violet and red) to the deviation of a mean color (typically yellow).

Step 2: Key Formula or Approach:

The formula for dispersive power (\(\omega\)) is: \[ \omega = \frac{Angular Dispersion}{Mean Deviation} = \frac{\delta_V - \delta_R}{\delta_Y} \]

For a prism with a small angle \(A\), the angle of deviation \(\delta\) is given by \(\delta = (\mu - 1)A\), where \(\mu\) is the refractive index of the material.

Substituting this into the formula for \(\omega\): \[ \omega = \frac{(\mu_V - 1)A - (\mu_R - 1)A}{(\mu_Y - 1)A} \]

The prism angle \(A\) cancels out from the numerator and the denominator: \[ \omega = \frac{\mu_V - \mu_R}{\mu_Y - 1} \]

Step 3: Detailed Explanation:

The final expression, \(\omega = \frac{\mu_V - \mu_R}{\mu_Y - 1}\), shows that the dispersive power depends only on the refractive indices of the prism's material for different wavelengths of light (\(\mu_V, \mu_R, \mu_Y\)). The refractive index is an intrinsic property of the material itself.

Therefore, the dispersive power depends on the nature of the material of the prism. It does not depend on the geometric properties of the prism, such as its angle (\(A\)), nor on how the light enters it, such as the angle of incidence.

Step 4: Final Answer:

Since dispersive power is determined solely by the refractive indices of the medium, it is a characteristic property of the material of the prism. Therefore, option (B) is correct.

\begin{quicktipbox

A key takeaway is that dispersion (the separation of colors) depends on both the prism's angle and the material, but \textit{dispersive power is a specific ratio that is an intrinsic property of the material alone. For example, a flint glass prism has a higher dispersive power than a crown glass prism, regardless of their shapes.

\end{quicktipbox Quick Tip: A key takeaway is that \textit{dispersion (the separation of colors) depends on both the prism's angle and the material, but dispersive power is a specific ratio that is an intrinsic property of the material alone. For example, a flint glass prism has a higher dispersive power than a crown glass prism, regardless of their shapes.

LASER action needs

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Concept:

LASER stands for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation. The core principle behind a laser is creating a condition where stimulated emission is more probable than absorption or spontaneous emission.

Step 2: Detailed Explanation:

For light amplification to occur, there must be more atoms or molecules in a higher energy (excited) state than in a lower energy (ground or intermediate) state. This non-equilibrium condition is known as population inversion or number inversion.

When population inversion is achieved, a photon passing through the medium is more likely to trigger a stimulated emission (creating an identical photon) than to be absorbed. This leads to a chain reaction and amplification of light.