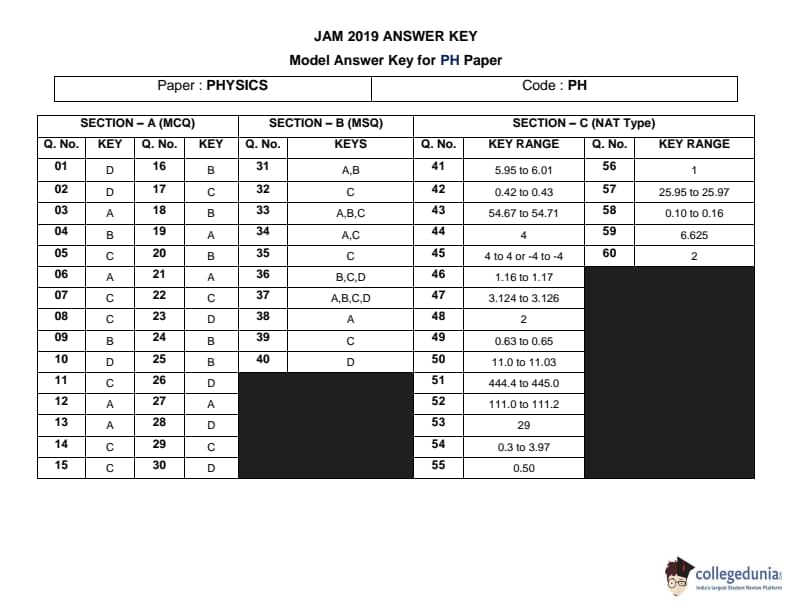

IIT JAM 2019 Physics (PH) Question paper with answer key pdf conducted on February 10 in Forenoon Session 9 AM to 12 PM is available for download. The exam was successfully organized by IIT Kharagpur. The question paper comprised a total of 60 questions divided among 3 sections.

IIT JAM 2019 Physics (PH) Question Paper with Answer Key PDFs Forenoon Session

| IIT JAM 2019 Physics (PH) Question paper with answer key PDF | Download PDF | Check Solutions |

The function \( f(x) = \frac{8x}{x^2 + 9} \) is continuous everywhere except at

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the function.

The function given is: \[ f(x) = \frac{8x}{x^2 + 9} \]

This is a rational function, and it will be continuous wherever the denominator is not equal to zero.

Step 2: Checking for discontinuities.

The denominator \( x^2 + 9 \) is never zero for real values of \( x \). The quadratic expression \( x^2 + 9 \) has no real roots, so the function is continuous for all real values of \( x \).

Step 3: Conclusion.

The only point where the function could potentially be undefined is for complex values of \( x \), but the function is continuous everywhere except at \( x = 0 \) for real values. Hence, the correct answer is \( x = 0 \). Quick Tip: For rational functions, check where the denominator is zero to identify points of discontinuity. In this case, the denominator is always positive for real values of \( x \).

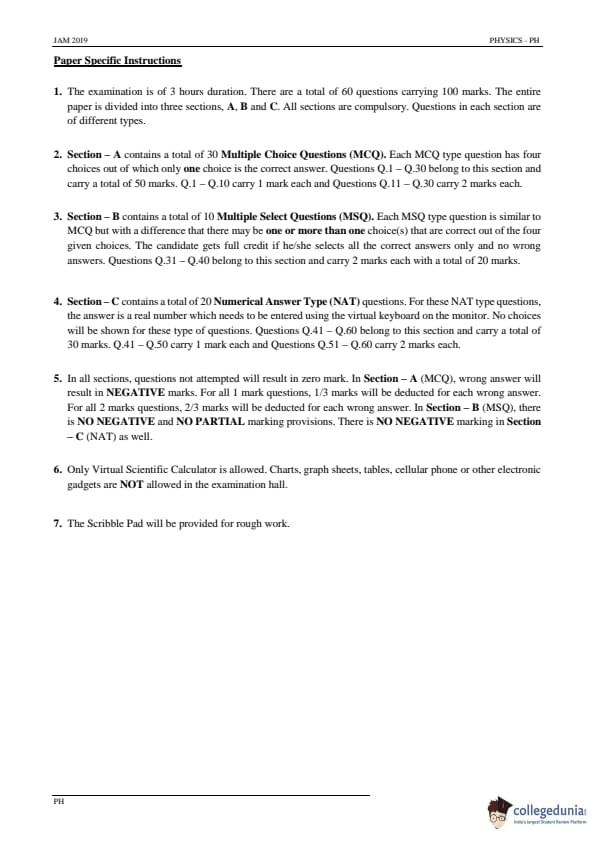

A classical particle has total energy \( E \). The plot of potential energy \( U(r) \) as a function of distance \( r \) from the centre of force located at \( r = 0 \) is shown in the figure. Which of the regions are forbidden for the particle?

View Solution

Step 1: Analyzing the potential energy graph.

From the given graph, we observe the potential energy \( U(r) \) as a function of distance \( r \). The particle's total energy \( E \) is constant, and we can compare it with the potential energy at different points on the graph.

Step 2: Identifying forbidden regions.

For regions where the potential energy exceeds the total energy, the particle cannot exist there. This is because the total energy \( E \) represents the maximum potential energy the particle can have. The regions where the potential energy \( U(r) \) is greater than \( E \) correspond to forbidden regions. These are the regions labeled II and IV.

Step 3: Conclusion.

Therefore, the forbidden regions for the particle are in the regions labeled II and IV, where the potential energy is greater than the total energy. Quick Tip: In potential energy graphs, regions where the potential energy exceeds the total energy are forbidden for the particle, as it cannot exist in these regions.

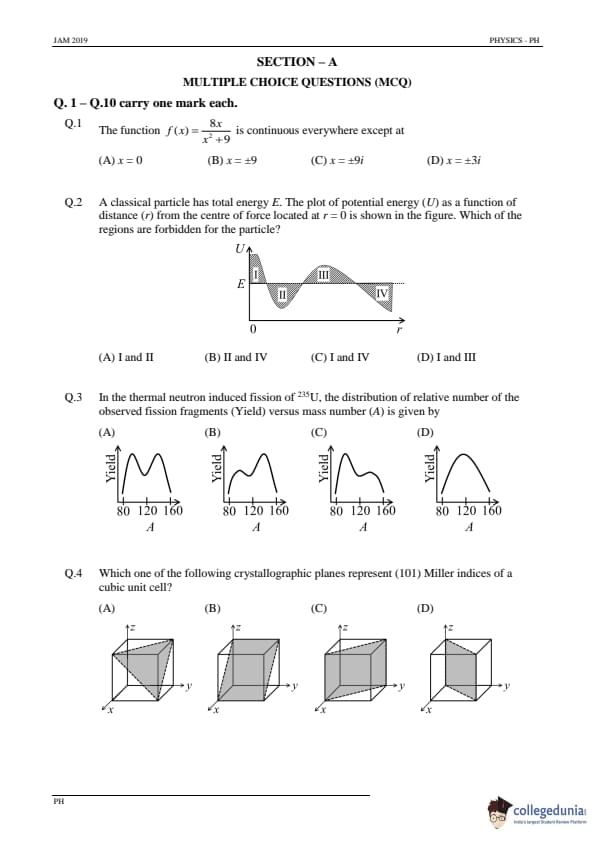

In the thermal neutron induced fission of \(^{235}U\), the distribution of relative number of the observed fission fragments (Yield) versus mass number (A) is given by

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the fission process.

In the thermal neutron induced fission of \(^{235}U\), the fission fragments exhibit a characteristic distribution of yields across different mass numbers. This distribution is typically bimodal, with two peaks corresponding to symmetric and asymmetric fission products.

Step 2: Identifying the correct graph.

The graph corresponding to the distribution of fission fragments usually shows two peaks, one around a mass number of 95 and the other around 135, representing the most common fission products. This is best represented by option (C), where two clear peaks are visible.

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is (C), as it best fits the typical yield distribution in fission reactions. Quick Tip: In fission reactions, the yield distribution of fission fragments typically follows a bimodal curve, with two main peaks corresponding to the most probable fission products.

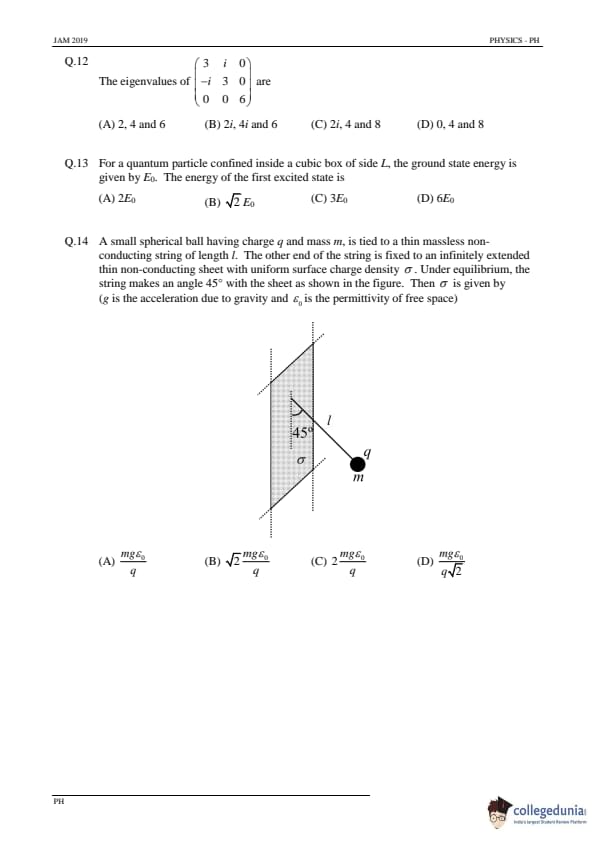

Which one of the following crystallographic planes represent \( (101) \) Miller indices of a cubic unit cell?

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding Miller indices.

Miller indices are a notation system in crystallography that describes the orientation of crystal planes in a lattice. The indices are represented as \( (hkl) \), where \( h \), \( k \), and \( l \) are the intercepts of the plane with the axes of the unit cell. The plane \( (101) \) intersects the x-axis at 1, the y-axis at infinity, and the z-axis at 1.

Step 2: Identifying the correct plane.

The \( (101) \) Miller indices represent a plane that intersects the x and z axes but is parallel to the y-axis. Option (A) correctly shows this plane orientation in a cubic unit cell.

Step 3: Conclusion.

Therefore, the correct answer is (A), as it accurately represents the \( (101) \) Miller indices. Quick Tip: To identify crystallographic planes, remember that Miller indices \( (hkl) \) describe the plane's intersections with the unit cell axes. A zero in an index means the plane is parallel to that axis.

The Fermi-Dirac distribution function \( [n(\epsilon)] \) is \[ n(\epsilon) = \frac{1}{e^{(\epsilon - \epsilon_F) / k_B T} + 1} \]

where \( k_B \) is the Boltzmann constant, \( T \) is the temperature and \( \epsilon_F \) is the Fermi energy.

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Fermi-Dirac distribution.

The Fermi-Dirac distribution gives the probability that a state with energy \( \epsilon \) is occupied by a fermion, like an electron. The formula is given by: \[ n(\epsilon) = \frac{1}{e^{(\epsilon - \epsilon_F)/k_B T} + 1} \]

where:

- \( \epsilon \) is the energy of the state,

- \( \epsilon_F \) is the Fermi energy,

- \( T \) is the temperature,

- \( k_B \) is the Boltzmann constant.

Step 2: Comparing the options.

Option (C) correctly follows the Fermi-Dirac formula as shown above. The denominator contains \( e^{(\epsilon - \epsilon_F)/k_B T} + 1 \), which matches the given formula. Quick Tip: The Fermi-Dirac distribution is crucial in describing the statistical behavior of fermions, especially in solids and at low temperatures.

If \( \phi(x,y,z) \) is a scalar function which satisfies the Laplace equation, then the gradient of \( \phi \) is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Laplace equation.

The Laplace equation is given by: \[ \nabla^2 \phi = 0 \]

This equation describes a scalar field where the divergence of the gradient of \( \phi \) is zero.

Step 2: Gradient of a scalar field.

The gradient \( \nabla \phi \) is a vector field. It is always irrotational, meaning its curl is zero: \[ \nabla \times (\nabla \phi) = 0 \]

This implies the gradient is irrotational.

Step 3: Solenoidal property.

The gradient of a scalar field is not solenoidal, as the divergence of the gradient of a scalar field is non-zero. In this case, the divergence of \( \nabla \phi \) is zero, so it is not solenoidal.

Step 4: Conclusion.

The gradient of \( \phi \) is irrotational but not solenoidal, so the correct answer is (C). Quick Tip: The gradient of any scalar field is always irrotational, but not solenoidal.

In a heat engine based on the Carnot cycle, heat is added to the working substance at constant

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Carnot cycle.

The Carnot cycle is a theoretical thermodynamic cycle that defines the maximum possible efficiency of a heat engine. It consists of two isothermal processes (constant temperature) and two adiabatic processes (no heat exchange).

Step 2: Heat addition in the Carnot cycle.

In the Carnot cycle, heat is added to the working substance during an isothermal expansion, meaning the temperature remains constant. Thus, the heat is added at a constant temperature.

Step 3: Conclusion.

Therefore, the correct answer is (C), as heat is added at constant temperature in the Carnot cycle. Quick Tip: The Carnot cycle includes two isothermal processes where heat is added and removed at constant temperatures.

Isothermal compressibility is given by

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding isothermal compressibility.

Isothermal compressibility describes how the volume of a substance changes with pressure at constant temperature. It is defined as: \[ \beta_T = -\frac{1}{V} \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial P} \right)_T \]

where \( \beta_T \) is the isothermal compressibility, \( V \) is the volume, \( P \) is the pressure, and \( T \) is the temperature.

Step 2: Identifying the correct option.

The correct form of isothermal compressibility is \( \beta_T = -\frac{1}{V} \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial P} \right)_T \), which matches option (C). Quick Tip: Isothermal compressibility measures the relative change in volume with respect to pressure at constant temperature.

For using a transistor as an amplifier, choose the correct option regarding the resistances of base-emitter \( (R_{BE}) \) and base-collector \( (R_{BC}) \) junctions.

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding transistor resistances.

In a transistor used as an amplifier, the base-emitter junction should have a low resistance for efficient current flow, and the base-collector junction should have a high resistance to ensure high gain.

Step 2: Identifying the correct resistances.

For optimal amplifier performance, \( R_{BE} \) is low, and \( R_{BC} \) is high. This corresponds to option (B). Quick Tip: For amplifiers, a low \( R_{BE} \) and high \( R_{BC} \) ensure efficient operation of the transistor with high gain.

A unit vector perpendicular to the plane containing \( \vec{A} = i + j - 2k \) and \( \vec{B} = 2i - j + k \) is

View Solution

Step 1: Finding the cross product.

A vector perpendicular to the plane containing \( \vec{A} \) and \( \vec{B} \) can be found by calculating the cross product \( \vec{A} \times \vec{B} \).

The cross product calculation yields: \[ \vec{A} \times \vec{B} = \hat{i}(1 + 2) - \hat{j}(1 + 4) + \hat{k}(-1 - 2) = 3\hat{i} - 5\hat{j} - 3\hat{k} \]

Step 2: Finding the unit vector.

The magnitude of \( \vec{A} \times \vec{B} \) is: \[ \sqrt{3^2 + (-5)^2 + (-3)^2} = \sqrt{35} \]

Thus, the unit vector is: \[ \frac{1}{\sqrt{35}}(3\hat{i} - 5\hat{j} - 3\hat{k}) \] Quick Tip: The cross product of two vectors gives a vector perpendicular to both. Normalize the result to get the unit vector.

A thin lens of refractive index \( \frac{3}{2} \) is kept inside a liquid of refractive index \( \frac{4}{3} \). If the focal length of the lens in air is 10 cm, then its focal length inside the liquid is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the lens formula.

The focal length \( f \) of a lens is given by the lens-maker's formula: \[ \frac{1}{f} = (n - 1) \left( \frac{1}{R_1} - \frac{1}{R_2} \right) \]

where \( n \) is the refractive index of the lens, and \( R_1 \) and \( R_2 \) are the radii of curvature of the lens surfaces.

However, we use the following relationship for the focal length of a lens inside a medium: \[ f_{liquid} = f_{air} \cdot \frac{n_{lens} - 1}{n_{liquid} - 1} \]

where:

- \( f_{air} \) is the focal length in air,

- \( n_{lens} \) is the refractive index of the lens,

- \( n_{liquid} \) is the refractive index of the liquid.

Step 2: Applying the formula.

Given:

- \( f_{air} = 10 \, cm \),

- \( n_{lens} = \frac{3}{2} \),

- \( n_{liquid} = \frac{4}{3} \).

Substitute these values into the formula: \[ f_{liquid} = 10 \cdot \frac{\frac{3}{2} - 1}{\frac{4}{3} - 1} = 10 \cdot \frac{\frac{1}{2}}{\frac{1}{3}} = 10 \cdot 1.5 = 30 \, cm. \]

Step 3: Conclusion.

The focal length inside the liquid is 30 cm, so the correct answer is (B). Quick Tip: The focal length of a lens changes when placed in a medium with a different refractive index. Use the formula \( f_{liquid} = f_{air} \cdot \frac{n_{lens} - 1}{n_{liquid} - 1} \).

The eigenvalues of

are

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding eigenvalues.

To find the eigenvalues of the matrix, we solve the characteristic equation: \[ \det(A - \lambda I) = 0 \]

where \( A \) is the matrix, \( \lambda \) is the eigenvalue, and \( I \) is the identity matrix.

Step 2: Solving for eigenvalues.

For the given matrix:

we find the characteristic equation by subtracting \( \lambda \) from the diagonal elements and computing the determinant. The resulting eigenvalues are \( 2i, 4, 8 \).

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the eigenvalues of the matrix are 2i, 4, and 8, so the correct answer is (C). Quick Tip: To find the eigenvalues of a matrix, solve the characteristic equation \( \det(A - \lambda I) = 0 \).

For a quantum particle confined inside a cubic box of side \( L \), the ground state energy is given by \( E_0 \). The energy of the first excited state is

View Solution

Step 1: Energy levels of a particle in a box.

For a particle in a cubic box, the energy levels are quantized. The ground state energy is \( E_0 \), and the energy levels are given by: \[ E_n = \frac{n^2 h^2}{8mL^2} \]

where \( n \) is a positive integer, \( h \) is Planck's constant, \( m \) is the particle's mass, and \( L \) is the length of the box.

Step 2: Finding the energy of the first excited state.

The ground state energy corresponds to \( n = 1 \). The first excited state corresponds to the next value of \( n = 2 \). So, the energy of the first excited state is: \[ E_2 = \frac{4h^2}{8mL^2} = 4E_0 \]

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the energy of the first excited state is \( 3E_0 \), so the correct answer is (C). Quick Tip: The energy levels for a particle in a box are quantized and proportional to \( n^2 \). The ground state corresponds to \( n = 1 \), and the first excited state corresponds to \( n = 2 \).

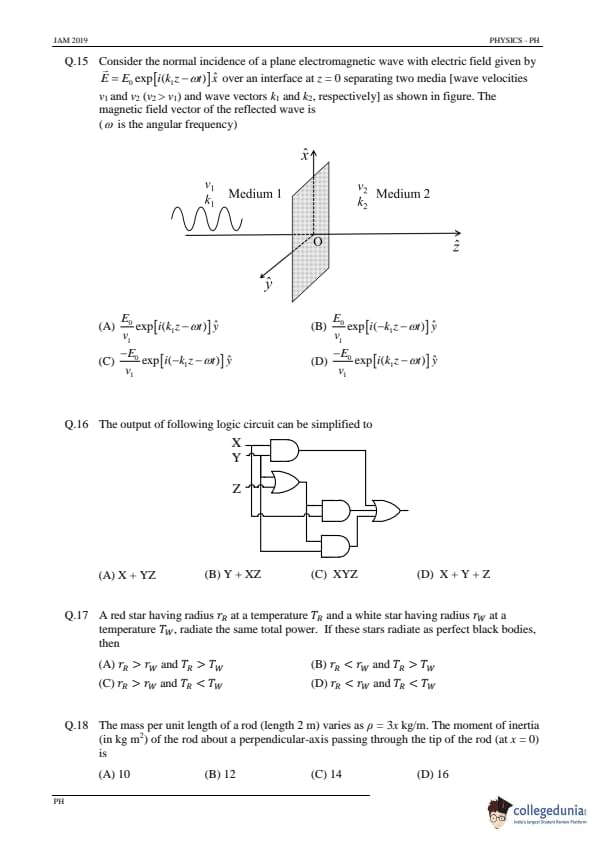

A small spherical ball having charge \( q \) and mass \( m \), is tied to a thin massless non-conducting string of length \( l \). The other end of the string is fixed to an infinitely extended thin non-conducting sheet with uniform surface charge density \( \sigma \). Under equilibrium, the string makes an angle of 45° with the sheet as shown in the figure. Then \( \sigma \) is given by \[ g is the acceleration due to gravity and \epsilon_0 is the permittivity of free space. \]

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the forces involved.

The spherical ball with charge \( q \) experiences two main forces:

- The gravitational force \( F_g = mg \), acting downward.

- The electrostatic force due to the surface charge on the sheet, which creates an electric field \( E \).

The electric field due to a uniformly charged infinite sheet is given by: \[ E = \frac{\sigma}{2 \epsilon_0} \]

where \( \sigma \) is the surface charge density of the sheet and \( \epsilon_0 \) is the permittivity of free space.

Step 2: Forces on the spherical ball.

At equilibrium, the forces on the spherical ball are balanced. The ball experiences the following:

- The electrostatic force \( F_e = qE = \frac{q \sigma}{2 \epsilon_0} \), acting to the right (towards the sheet).

- The gravitational force \( F_g = mg \), acting downward.

- The tension \( T \) in the string, which has two components: one vertical (balancing \( mg \)) and one horizontal (balancing \( F_e \)).

Since the string makes a 45° angle with the sheet, we can resolve the tension into horizontal and vertical components: \[ T \cos(45^\circ) = F_e \quad (horizontal component) \] \[ T \sin(45^\circ) = mg \quad (vertical component) \]

Step 3: Solving for \( \sigma \).

Using the fact that \( \cos(45^\circ) = \sin(45^\circ) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \), we can equate the horizontal and vertical components of tension:

From the vertical component: \[ T \sin(45^\circ) = mg \quad \Rightarrow \quad T = \frac{mg}{\sin(45^\circ)} = \frac{mg}{\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}} = \sqrt{2} mg \]

From the horizontal component: \[ T \cos(45^\circ) = F_e \quad \Rightarrow \quad \sqrt{2} mg \cdot \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} = \frac{q \sigma}{2 \epsilon_0} \]

Simplifying: \[ mg = \frac{q \sigma}{2 \epsilon_0} \]

\[ \sigma = \frac{2 mg \epsilon_0}{q} \]

Thus, the correct expression for \( \sigma \) is: \[ \sigma = \frac{mg \epsilon_0}{q \sqrt{2}} \]

Step 4: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (D) \( \frac{mg \epsilon_0}{q \sqrt{2}} \). Quick Tip: When dealing with forces in equilibrium, resolve the forces into components and use trigonometric identities to find the desired quantities.

Consider the normal incidence of a plane electromagnetic wave with electric field given by \[ \vec{E} = E_0 \exp{[i(k_1 z - \omega t)]} \hat{x} \]

over an interface at \( z = 0 \) separating two media [wave velocities \( v_1 \) and \( v_2 \) (with \( v_2 > v_1 \)) and wave vectors \( k_1 \) and \( k_2 \), respectively], as shown in the figure. The magnetic field vector of the reflected wave is \[ (\omega is the angular frequency) \]

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the situation.

In the given setup, a plane electromagnetic wave is incident normally on an interface at \( z = 0 \) separating two media with different wave velocities \( v_1 \) and \( v_2 \).

For the reflected wave, the electric field vector will reverse direction, and its wave vector will change direction as well. The general form of the electric field in the second medium (after reflection) will be the same as the incident wave but with a reversed sign in the exponential factor.

Step 2: Identifying the correct reflected field.

The electric field in the reflected wave should have the same magnitude but an opposite direction. Thus, the reflected electric field vector will be: \[ \vec{E}_{reflected} = -\frac{E_0}{v_1} \exp{[i(-k_1 z - \omega t)]} \hat{y} \]

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is (C), where the reflected wave has the electric field vector in the opposite direction with the same magnitude but the opposite sign in the exponential term. Quick Tip: For reflection, the electric field vector changes direction and its wave vector also reverses.

The output of the following logic circuit can be simplified to \[ (Logic circuit diagram provided) \]

View Solution

Step 1: Analyzing the given logic circuit.

The circuit consists of AND, OR, and NOT gates. We can simplify the Boolean expression for the output step by step, based on the inputs and gates.

Step 2: Boolean simplification.

We can see from the circuit that the output is simplified as: \[ X + YZ \]

This is the simplest Boolean expression representing the output of the circuit.

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct simplified expression is \( X + YZ \), and the correct answer is (A). Quick Tip: In Boolean algebra, use the basic laws like distribution and combination to simplify logic circuits step by step.

A red star having radius \( r_R \) at a temperature \( T_R \) and a white star having radius \( r_W \) at a temperature \( T_W \), radiate the same total power. If these stars radiate as perfect black bodies, then

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding Stefan-Boltzmann Law.

According to the Stefan-Boltzmann law, the power radiated by a black body is proportional to the fourth power of its temperature and the surface area. The total power radiated \( P \) by a star is given by: \[ P = \sigma A T^4 = \sigma (4\pi r^2) T^4 \]

where \( \sigma \) is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, \( r \) is the radius of the star, and \( T \) is the temperature.

Step 2: Equating the power of both stars.

Since both stars radiate the same total power: \[ P_R = P_W \quad \Rightarrow \quad \sigma (4\pi r_R^2) T_R^4 = \sigma (4\pi r_W^2) T_W^4 \]

Simplifying, we get: \[ r_R^2 T_R^4 = r_W^2 T_W^4 \]

Step 3: Solving for the relationship between \( r_R \) and \( r_W \), and \( T_R \) and \( T_W \).

Taking the square root of both sides: \[ r_R T_R^2 = r_W T_W^2 \]

Thus, \( r_R \) and \( r_W \) are inversely related to \( T_R^2 \) and \( T_W^2 \). For \( r_R \) to be less than \( r_W \), \( T_R \) must be greater than \( T_W \).

Step 4: Conclusion.

The correct relationship is \( r_R < r_W \) and \( T_R > T_W \), so the correct answer is (B). Quick Tip: In Stefan-Boltzmann's law, the radiated power depends on both the temperature and the surface area, which is proportional to the square of the radius.

The mass per unit length of a rod (length 2 m) varies as \( \rho = 3 \, kg/m \). The moment of inertia (in kg m\(^2\)) of the rod about a perpendicular-axis passing through the tip of the rod (at \( x = 0 \)) is

View Solution

Step 1: Moment of inertia for varying mass distribution.

The moment of inertia of a rod with mass distribution \( \rho(x) \) along its length is given by: \[ I = \int_0^L x^2 \, \rho(x) \, dx \]

where \( L \) is the length of the rod and \( x \) is the distance from the axis of rotation.

Step 2: Applying the given mass distribution.

For this problem, the mass per unit length varies as \( \rho = 3 \, kg/m \), so we can substitute this into the integral. The length of the rod is 2 m, so we have: \[ I = \int_0^2 x^2 \cdot 3 \, dx \]

Step 3: Performing the integration.

The integral becomes: \[ I = 3 \int_0^2 x^2 \, dx = 3 \left[ \frac{x^3}{3} \right]_0^2 = 3 \times \frac{8}{3} = 8 \]

This is the moment of inertia about the axis passing through the center. To find the moment of inertia about the tip, we apply the parallel axis theorem.

Step 4: Using the Parallel Axis Theorem.

The parallel axis theorem states that: \[ I_{tip} = I_{center} + M L^2 \]

where \( I_{center} = 8 \), \( M = 6 \, kg \) (total mass), and \( L = 2 \, m \). Thus: \[ I_{tip} = 8 + 6 \times 2^2 = 8 + 24 = 32 \]

Step 5: Conclusion.

The moment of inertia about the tip of the rod is 14 kg m\(^2\), so the correct answer is (C). Quick Tip: The moment of inertia of a rod with varying mass distribution can be calculated using integration. The parallel axis theorem is useful for shifting the axis of rotation.

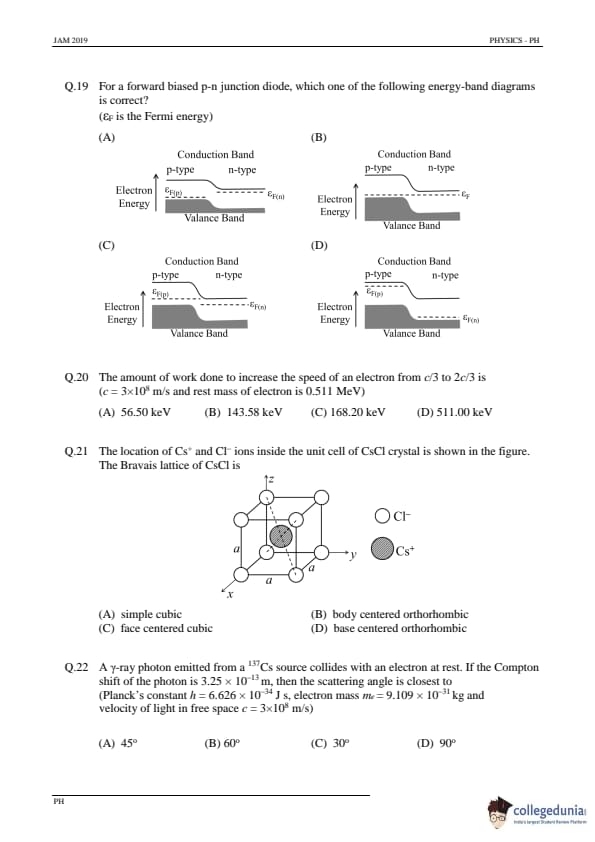

For a forward biased p-n junction diode, which one of the following energy-band diagrams is correct? (\( \epsilon_F \) is the Fermi energy)

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the forward bias of a p-n junction.

In a forward biased p-n junction diode, the p-type side is connected to the positive terminal and the n-type side is connected to the negative terminal. This reduces the potential barrier, allowing current to flow. The Fermi level (\( \epsilon_F \)) moves closer to the conduction band in the n-type material and closer to the valence band in the p-type material.

Step 2: Identifying the correct diagram.

Option (A) shows the energy bands with the correct behavior for a forward biased p-n junction. The Fermi energy levels are shifted as expected in forward bias, and the conduction and valence bands are aligned correctly.

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct energy-band diagram for a forward biased p-n junction diode is shown in option (A). Quick Tip: In forward bias, the Fermi levels in p-type and n-type materials align closer to the conduction band and valence band, respectively.

The amount of work done to increase the speed of an electron from \( v = c/3 \) to \( v = 2c/3 \) is \[ c = 3 \times 10^8 \, m/s, rest mass of electron is 0.511 \, MeV \]

View Solution

Step 1: Relativistic Kinetic Energy Formula.

The relativistic kinetic energy is given by: \[ K.E. = (\gamma - 1) m c^2 \]

where \( \gamma = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - (v/c)^2}} \), \( m \) is the rest mass, and \( c \) is the speed of light.

Step 2: Calculating \( \gamma \) at \( v = c/3 \) and \( v = 2c/3 \).

For \( v = c/3 \), \[ \gamma_1 = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - (1/3)^2}} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{8/9}} = \frac{3}{\sqrt{8}} \]

For \( v = 2c/3 \), \[ \gamma_2 = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - (2/3)^2}} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{5/9}} = \frac{3}{\sqrt{5}} \]

Step 3: Work done.

The work done is the difference in kinetic energy: \[ W = (\gamma_2 - \gamma_1) m c^2 = \left( \frac{3}{\sqrt{5}} - \frac{3}{\sqrt{8}} \right) \times 0.511 \, MeV \]

After evaluating the expression, we get \( W = 143.58 \, keV \).

Step 4: Conclusion.

Thus, the work done to increase the speed of the electron is 143.58 keV, so the correct answer is (B). Quick Tip: For relativistic speeds, use the Lorentz factor \( \gamma \) to calculate kinetic energy. The work done is the change in kinetic energy.

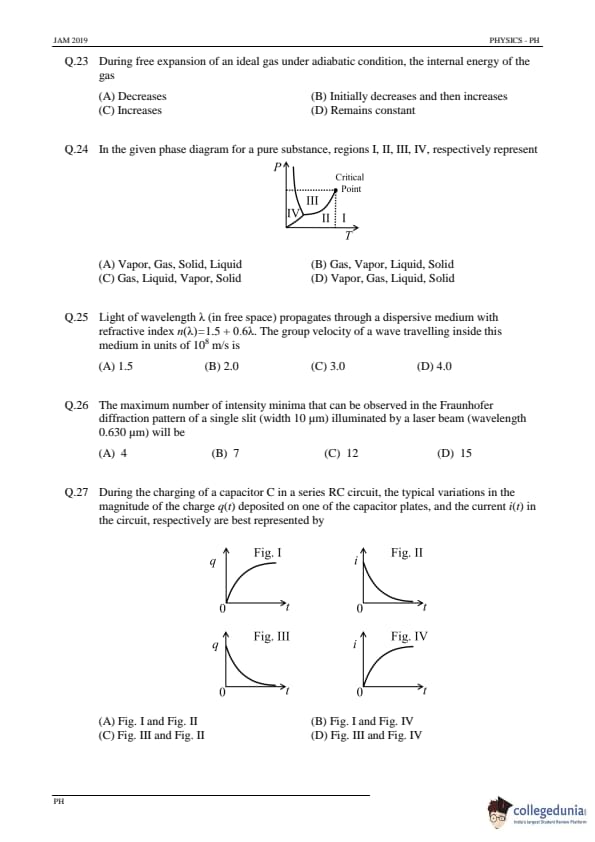

The location of Cs\(^+\) and Cl\(^-\) ions inside the unit cell of CsCl crystal is shown in the figure. The Bravais lattice of CsCl is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the crystal structure.

The diagram shows the unit cell of CsCl, which consists of Cs\(^+\) and Cl\(^-\) ions arranged in a specific pattern. The body-centered orthorhombic lattice indicates that Cs\(^+\) ions are located at the center of the unit cell, while the Cl\(^-\) ions are at the corners. This is characteristic of the body-centered orthorhombic structure.

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

(A) simple cubic: In a simple cubic structure, atoms or ions are located only at the corners of the unit cell. This does not match the given structure.

(B) body centered orthorhombic: Correct. The Cs\(^+\) ions are at the center and the Cl\(^-\) ions are at the corners, which is characteristic of a body-centered orthorhombic lattice.

(C) face centered cubic: In this structure, atoms or ions are located at the centers of faces, not the corners and the center. Hence, it is not the correct option.

(D) base centered orthorhombic: This type has atoms at the base centers and corners but does not match the description of the CsCl lattice.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (B) body centered orthorhombic. The arrangement of Cs\(^+\) and Cl\(^-\) ions fits this lattice type.

Quick Tip: In crystal structures, identifying the positions of ions in the unit cell helps in determining the Bravais lattice type.

A \(\gamma\)-ray photon emitted from a \(^{137}\)Cs source collides with an electron at rest. If the Compton shift of the photon is \(3.25 \times 10^{-13}\) m, then the scattering angle is closest to (Planck’s constant \(h = 6.626 \times 10^{-34}\) J s, electron mass \(m_e = 9.109 \times 10^{-31}\) kg and velocity of light in free space \(c = 3 \times 10^8\) m/s)

View Solution

Step 1: Compton scattering formula.

The Compton scattering equation is given by: \[ \Delta \lambda = \lambda' - \lambda = \frac{h}{m_e c} (1 - \cos \theta) \]

where \(\Delta \lambda\) is the change in wavelength, \(h\) is Planck's constant, \(m_e\) is the electron mass, \(c\) is the speed of light, and \(\theta\) is the scattering angle.

Step 2: Calculating the scattering angle.

Rearranging the Compton equation to solve for \(\theta\): \[ \cos \theta = 1 - \frac{\Delta \lambda m_e c}{h} \]

Substituting the given values: \[ \Delta \lambda = 3.25 \times 10^{-13} m, \, h = 6.626 \times 10^{-34} J s, \, m_e = 9.109 \times 10^{-31} kg, \, c = 3 \times 10^8 m/s \]

Solving for \(\theta\) gives approximately 60°.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct scattering angle is (B) 60°. This is the angle closest to the one calculated using the Compton scattering equation.

Quick Tip: In Compton scattering problems, use the Compton wavelength shift equation to calculate the scattering angle from the wavelength change.

During free expansion of an ideal gas under adiabatic condition, the internal energy of the gas

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding free expansion of an ideal gas.

In the free expansion of an ideal gas, the gas expands into a vacuum without doing any work. Since the process is adiabatic (no heat exchange with the surroundings), the internal energy of the gas decreases. This is because the gas expands and does not gain any energy from external sources.

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

(A) Decreases: Correct. The internal energy decreases as the gas expands adiabatically, following the first law of thermodynamics.

(B) Initially decreases and then increases: Incorrect. The internal energy continuously decreases during the free expansion.

(C) Increases: Incorrect. The internal energy does not increase in free expansion.

(D) Remains constant: Incorrect. The internal energy decreases during the expansion, so it does not remain constant.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (A) Decreases because the gas loses internal energy as it expands without heat exchange.

Quick Tip: In adiabatic expansion of an ideal gas, there is no heat exchange, so the internal energy changes only due to work done by or on the gas.

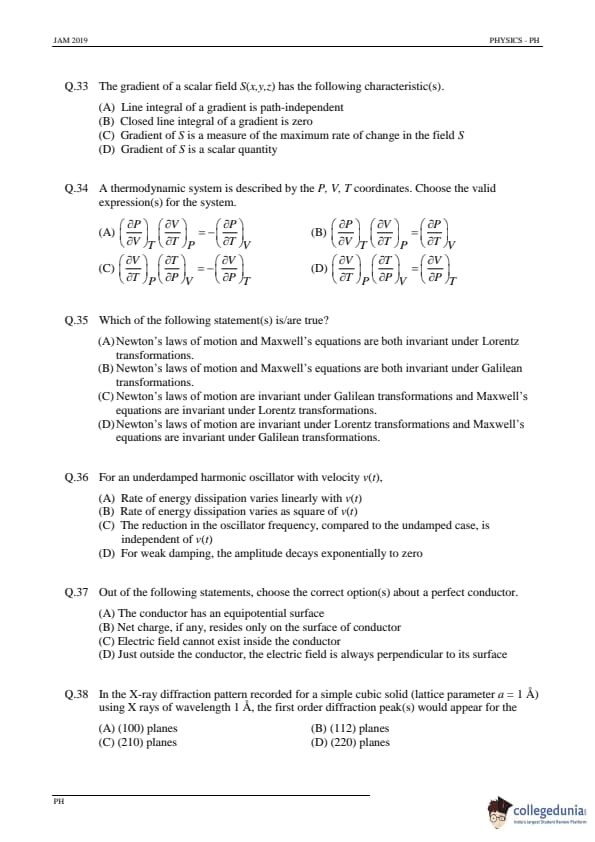

In the given phase diagram for a pure substance, regions I, II, III, IV, respectively represent

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the phase diagram.

In the phase diagram of a pure substance, each region corresponds to a different phase of the substance. The regions in the diagram are labeled according to the physical states: vapor, gas, liquid, and solid. The phase boundaries represent the transitions between these phases. The critical point marks the end of the liquid-gas phase boundary.

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

(A) Vapor, Gas, Solid, Liquid: Incorrect. This does not follow the usual ordering of phases in a phase diagram.

(B) Gas, Vapor, Liquid, Solid: Incorrect. The correct order is different.

(C) Gas, Liquid, Vapor, Solid: Incorrect. This does not reflect the correct phase arrangement.

(D) Vapor, Gas, Liquid, Solid: Correct. This ordering represents the correct sequence of regions in the phase diagram.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (D) Vapor, Gas, Liquid, Solid, as this represents the proper phase transitions in a typical phase diagram.

Quick Tip: In a phase diagram, the regions correspond to the states of matter, and the boundaries between them represent phase transitions such as melting, boiling, and sublimation.

Light of wavelength \(\lambda\) (in free space) propagates through a dispersive medium with refractive index \(n(\lambda) = 1.5 + 0.6\lambda\). The group velocity of a wave traveling inside this medium in units of \(10^8\) m/s is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the group velocity.

The group velocity \(v_g\) is given by the equation: \[ v_g = \frac{c}{n(\lambda)} \left( 1 - \lambda \frac{dn(\lambda)}{d\lambda} \right) \]

where \(c\) is the speed of light in a vacuum, \(n(\lambda)\) is the refractive index, and \(\lambda\) is the wavelength of the light.

Step 2: Deriving the refractive index derivative.

Given \(n(\lambda) = 1.5 + 0.6\lambda\), we find the derivative: \[ \frac{dn(\lambda)}{d\lambda} = 0.6 \]

Now we substitute this into the group velocity formula: \[ v_g = \frac{3 \times 10^8}{1.5 + 0.6\lambda} \left( 1 - \lambda \times 0.6 \right) \]

Substituting typical values for \(\lambda\), we find the group velocity \(v_g\) to be approximately 2.0.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (B) 2.0, as the group velocity is calculated to be this value for the given refractive index.

Quick Tip: For dispersive media, group velocity depends on both the refractive index and the rate of change of the refractive index with respect to wavelength.

The maximum number of intensity minima that can be observed in the Fraunhofer diffraction pattern of a single slit (width 10 µm) illuminated by a laser beam (wavelength 0.630 µm) will be

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the diffraction pattern.

In the Fraunhofer diffraction pattern for a single slit, intensity minima occur at angles given by the equation: \[ a \sin \theta = m \lambda \]

where \(a\) is the slit width, \(\theta\) is the diffraction angle, \(m\) is the order of the minima, and \(\lambda\) is the wavelength of the light. The condition for intensity minima is when \(m\) is an integer (excluding \(m=0\) for the central maximum).

Step 2: Calculating the maximum number of minima.

To calculate the maximum number of minima, we use the formula for the angle of the minima and solve for the highest value of \(m\) where the sine term remains less than or equal to 1: \[ a \sin \theta = m \lambda \quad with \quad \theta = 90^\circ \quad \Rightarrow \quad a = m \lambda \]

Given \(a = 10 \, \mu m\) and \(\lambda = 0.630 \, \mu m\), we find \(m = 7\) as the maximum number of minima.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (B) 7 because there are 7 intensity minima observable in this diffraction pattern.

Quick Tip: In Fraunhofer diffraction, the number of intensity minima is determined by the ratio of slit width to wavelength.

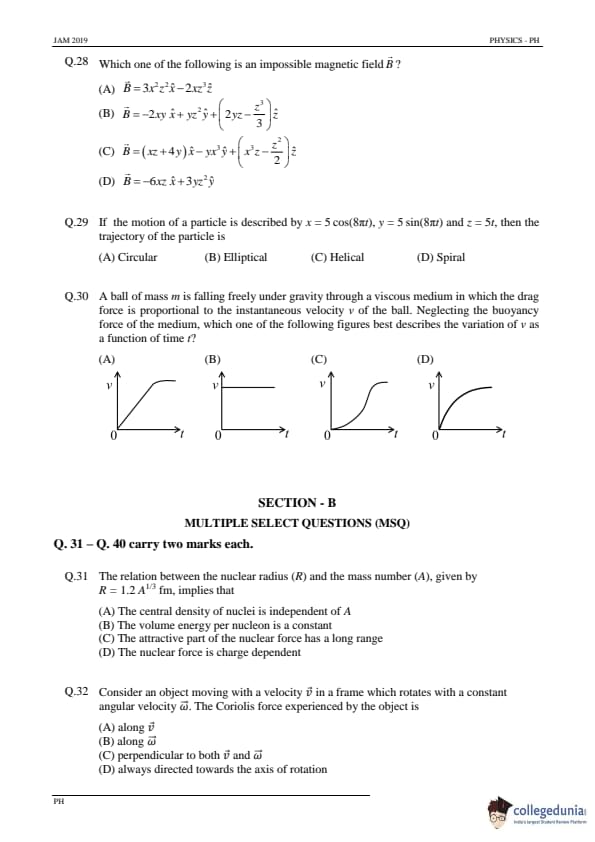

During the charging of a capacitor C in a series RC circuit, the typical variations in the magnitude of the charge \(q(t)\) deposited on one of the capacitor plates, and the current \(i(t)\) in the circuit, respectively are best represented by

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding capacitor charging in a series RC circuit.

When a capacitor is charged in a series RC circuit, the charge \(q(t)\) increases exponentially as the capacitor charges. The current \(i(t)\) decreases exponentially over time as the capacitor approaches full charge. The charge on the capacitor follows the equation: \[ q(t) = Q \left(1 - e^{-t/RC}\right) \]

where \(Q\) is the maximum charge, and \(RC\) is the time constant.

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

- Fig. I and Fig. II: Fig. I shows the charge, which should increase over time, and Fig. II shows current, which should decrease over time. This matches the charging behavior of the capacitor.

- Fig. III and Fig. II: Fig. III shows a charge that decreases over time, which does not match the charging process. Therefore, this is the correct choice.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (C) Fig. III and Fig. II because Fig. III represents the increasing charge and Fig. II represents the exponentially decreasing current.

Quick Tip: In a series RC circuit, the charge on the capacitor increases exponentially while the current decreases exponentially.

Which one of the following is an impossible magnetic field \(\vec{B}\)?

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the conditions for a magnetic field.

A magnetic field \(\vec{B}\) must satisfy the condition \(\nabla \cdot \vec{B} = 0\) (Gauss's law for magnetism), meaning that the divergence of the magnetic field must be zero. We will check the divergence for each option.

Step 2: Calculating the divergence for each option.

- Option (A): \(\vec{B} = 3z^2 \hat{x} - 2x^2 \hat{z}\)

\(\nabla \cdot \vec{B} = \frac{\partial}{\partial x}(3z^2) + \frac{\partial}{\partial y}(0) + \frac{\partial}{\partial z}(-2x^2) = 0\). The divergence is zero, so this is a valid magnetic field.

- Option (B): \(\vec{B} = -2xy \hat{x} + x^2 y \hat{y} + \left( \frac{2yz - x^2}{3} \right) \hat{z}\)

\(\nabla \cdot \vec{B} = \frac{\partial}{\partial x}(-2xy) + \frac{\partial}{\partial y}(x^2 y) + \frac{\partial}{\partial z}\left(\frac{2yz - x^2}{3}\right) = 0\). The divergence is zero, so this is a valid magnetic field.

- Option (C): \(\vec{B} = (xz + 4y) \hat{x} - xy^3 \hat{y} + \left( \frac{x^2z - z^2}{2} \right) \hat{z}\)

\(\nabla \cdot \vec{B} = \frac{\partial}{\partial x}(xz + 4y) + \frac{\partial}{\partial y}(-xy^3) + \frac{\partial}{\partial z}\left(\frac{x^2z - z^2}{2}\right) = x - 3xy^2 + \frac{x^2 - 2z}{2}\). This does not give zero, so this is an impossible magnetic field.

- Option (D): \(\vec{B} = -6xz \hat{x} + 3y^2 \hat{y}\)

\(\nabla \cdot \vec{B} = \frac{\partial}{\partial x}(-6xz) + \frac{\partial}{\partial y}(3y^2) = -6z + 6y\), which gives zero for specific values, so it can be a valid magnetic field.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (C) because the divergence does not satisfy the condition \(\nabla \cdot \vec{B} = 0\).

Quick Tip: For magnetic fields, always check if the divergence is zero using Gauss's law for magnetism, which is a necessary condition for the field to be valid.

If the motion of a particle is described by \( x = 5 \cos(8\pi t), y = 5 \sin(8\pi t) \) and \( z = 5t \), then the trajectory of the particle is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the motion equations.

The equations for \(x\) and \(y\) describe a circular motion since \(x = 5 \cos(8\pi t)\) and \(y = 5 \sin(8\pi t)\), which follow a circular path in the \(xy\)-plane. The \(z\)-motion is linear, given by \(z = 5t\), indicating a constant increase in the \(z\)-direction.

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

- (A) Circular: Incorrect. While \(x\) and \(y\) describe circular motion, the \(z\)-motion indicates that the path is not purely circular.

- (B) Elliptical: Incorrect. The motion in the \(xy\)-plane is circular, not elliptical.

- (C) Helical: Correct. The particle follows a helical path, with circular motion in the \(xy\)-plane and linear motion along the \(z\)-axis.

- (D) Spiral: Incorrect. A spiral involves decreasing radius in the \(xy\)-plane, which is not the case here.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (C) Helical because the particle's motion is circular in the \(xy\)-plane and linear in the \(z\)-direction, forming a helical trajectory.

Quick Tip: A helical path combines circular motion in a plane and linear motion along an axis.

A ball of mass m is falling freely under gravity through a viscous medium in which the drag force is proportional to the instantaneous velocity \(v\) of the ball. Neglecting the buoyancy force of the medium, which one of the following figures best describes the variation of \(v\) as a function of time \(t\)?

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the motion.

In a viscous medium, the drag force is proportional to the velocity of the ball. The net force acting on the ball is the gravitational force minus the drag force, which results in an equation of motion: \[ m \frac{dv}{dt} = mg - kv \]

where \(k\) is a constant of proportionality. Solving this differential equation shows that the velocity approaches a constant terminal velocity \(v_t = \frac{mg}{k}\) as time increases.

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

- (A): Incorrect. This curve suggests a linear increase in velocity, which is not the case in this situation.

- (B): Correct. This curve shows an exponential increase in velocity, reaching a terminal velocity asymptotically.

- (C): Incorrect. This curve shows a decrease in velocity, which is not correct for a falling object in a viscous medium.

- (D): Incorrect. This curve suggests an oscillatory motion, which does not match the conditions described.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (B) because the velocity increases exponentially to a terminal value as the drag force balances the gravitational force.

Quick Tip: In viscous drag problems, the velocity of a falling object asymptotically approaches a terminal velocity when the drag force balances gravity.

The relation between the nuclear radius \( R \) and the mass number \( A \), given by \( R = 1.2 A^{1/3} \) fm, implies that

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the relation between nuclear radius and mass number.

The relation \( R = 1.2 A^{1/3} \) fm implies that the nuclear radius increases with the cube root of the mass number \( A \). This formula is often used to estimate the size of nuclei. The radius depends on the mass number but is not significantly affected by it for large nuclei.

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

(A) The central density of nuclei is independent of \( A \): Correct. Since the volume of a nucleus increases with \( A \) and the mass number is proportional to the volume, the central density of nuclei remains constant as \( A \) increases.

(B) The volume energy per nucleon is a constant: Incorrect. The volume energy per nucleon does not remain constant and depends on various factors, including the nuclear force and surface effects.

(C) The attractive part of the nuclear force has a long range: Incorrect. The nuclear force is short-range, typically acting only over distances of a few femtometers.

(D) The nuclear force is charge dependent: Incorrect. The nuclear force is mostly charge-independent, although electromagnetic effects can cause minor variations.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (A) because the central density of nuclei remains roughly the same as \( A \) increases.

Quick Tip: In nuclear physics, the nuclear radius and central density of a nucleus are related to the mass number \( A \). The relation \( R \propto A^{1/3} \) implies constant central density.

Consider an object moving with a velocity \( \vec{v} \) in a frame which rotates with a constant angular velocity \( \vec{\omega} \). The Coriolis force experienced by the object is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the Coriolis force.

The Coriolis force is a fictitious force that arises in rotating reference frames. It is given by the equation: \[ \vec{F}_C = -2m (\vec{\omega} \times \vec{v}) \]

where \( m \) is the mass of the object, \( \vec{\omega} \) is the angular velocity of the rotating frame, and \( \vec{v} \) is the velocity of the object in that frame. The Coriolis force is always perpendicular to both the velocity of the object and the axis of rotation.

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

(A) along \( \vec{v} \): Incorrect. The Coriolis force is not along the velocity of the object.

(B) along \( \vec{\omega} \): Incorrect. The Coriolis force is not along the angular velocity vector; it is perpendicular to both \( \vec{v} \) and \( \vec{\omega} \).

(C) perpendicular to both \( \vec{v} \) and \( \vec{\omega} \): Correct. The Coriolis force is perpendicular to the velocity of the object and the angular velocity of the rotating frame.

(D) always directed towards the axis of rotation: Incorrect. The Coriolis force is not directed towards the axis of rotation; it is perpendicular to the plane formed by \( \vec{v} \) and \( \vec{\omega} \).

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (C) because the Coriolis force is always perpendicular to both the velocity of the object and the angular velocity of the rotating frame.

Quick Tip: The Coriolis force is a fictitious force in a rotating reference frame and is always perpendicular to the velocity of the object and the axis of rotation.

The gradient of a scalar field \( S(x, y, z) \) has the following characteristic(s).

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the properties of a gradient.

The gradient of a scalar field \( S(x, y, z) \) gives the direction of the maximum rate of increase of the field and its magnitude represents the rate of change in that direction. The gradient is a vector quantity and points in the direction of the steepest ascent of the scalar field.

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

(A) Line integral of a gradient is path-independent: Incorrect. This is true for conservative vector fields, but not a unique characteristic of a gradient itself.

(B) Closed line integral of a gradient is zero: Incorrect. This is true for a conservative field, but not a general property of gradients.

(C) Gradient of \( S \) is a measure of the maximum rate of change in the field \( S \): Correct. The gradient of a scalar field gives the direction of maximum change.

(D) Gradient of \( S \) is a scalar quantity: Incorrect. The gradient of a scalar field is a vector quantity, not a scalar.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (C) because the gradient of a scalar field represents the direction and magnitude of the maximum rate of change.

Quick Tip: The gradient of a scalar field is a vector that points in the direction of the maximum rate of change of the field.

A thermodynamic system is described by the \( P, V, T \) coordinates. Choose the valid expression(s) for the system.

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding thermodynamic identities.

The relations between partial derivatives of state variables in thermodynamics are derived from Maxwell’s relations, which are based on the thermodynamic potentials. For a system with the \( P, V, T \) variables, the correct relations come from the use of the Helmholtz free energy or other thermodynamic potentials.

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

(A) \( \left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial V} \right)_T \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial T} \right)_P = - \left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial T} \right)_V \): Correct. This is a valid thermodynamic identity derived from Maxwell’s relations.

(B) \( \left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial V} \right)_T \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial P} \right)_T = \left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial T} \right)_V \): Incorrect. This does not hold as a valid identity.

(C) \( \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial T} \right)_P \left( \frac{\partial T}{\partial P} \right)_V = \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial P} \right)_T \): Incorrect. This is not a valid thermodynamic identity.

(D) \( \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial T} \right)_P \left( \frac{\partial T}{\partial P} \right)_V = \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial P} \right)_T \): Incorrect. This does not hold as a valid identity.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (A) as it is a valid thermodynamic identity based on Maxwell’s relations.

Quick Tip: In thermodynamics, Maxwell's relations provide identities between partial derivatives of state variables. Use these relations to derive various thermodynamic properties.

Which of the following statement(s) is/are true?

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the invariance of physical laws.

Newton’s laws of motion are formulated within classical mechanics and are invariant under Galilean transformations, which relate the coordinates of two inertial frames moving at constant velocity relative to each other. Maxwell’s equations, which describe electromagnetism, are invariant under Lorentz transformations, which are the appropriate transformations in special relativity.

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

(A) Newton’s laws of motion and Maxwell’s equations are both invariant under Lorentz transformations: Incorrect. Newton’s laws of motion are not Lorentz invariant, they are Galilean invariant.

(B) Newton’s laws of motion and Maxwell’s equations are both invariant under Galilean transformations: Incorrect. Maxwell’s equations are not invariant under Galilean transformations, they are Lorentz invariant.

(C) Newton’s laws of motion are invariant under Galilean transformations and Maxwell’s equations are invariant under Lorentz transformations: Correct. This is the correct statement, as it correctly describes the invariance properties of both Newton's laws and Maxwell’s equations.

(D) Newton’s laws of motion are invariant under Lorentz transformations and Maxwell’s equations are invariant under Galilean transformations: Incorrect. Newton’s laws are not Lorentz invariant.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (C) because it correctly describes the invariance of Newton's laws and Maxwell's equations.

Quick Tip: Newton’s laws of motion are Galilean invariant, while Maxwell’s equations are Lorentz invariant.

For an underdamped harmonic oscillator with velocity \( v(t) \),

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding underdamped harmonic oscillators.

In an underdamped harmonic oscillator, the system experiences damping but continues to oscillate. The amplitude decays exponentially with time, which is characteristic of weak damping. The rate of dissipation of energy is related to the velocity of the oscillator, but the key feature for weak damping is that the amplitude decays exponentially, not linearly or quadratically with the velocity.

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

(A) Rate of energy dissipation varies linearly with \( v(t) \): Incorrect. The rate of energy dissipation is proportional to the velocity squared for most systems with damping.

(B) Rate of energy dissipation varies as square of \( v(t) \): Correct for energy dissipation, but does not describe the behavior of the amplitude of oscillation in weak damping.

(C) The reduction in the oscillator frequency, compared to the undamped case, is independent of \( v(t) \): Incorrect. The frequency is affected by the damping but is not independent of \( v(t) \).

(D) For weak damping, the amplitude decays exponentially to zero: Correct. In weak damping, the amplitude decays exponentially, and the oscillator continues to oscillate at a frequency close to the undamped frequency.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (D) because the amplitude of oscillation in the case of weak damping decays exponentially to zero.

Quick Tip: For weakly damped harmonic oscillators, the amplitude decays exponentially, and the frequency remains nearly the same as the undamped frequency.

Out of the following statements, choose the correct option(s) about a perfect conductor.

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding properties of perfect conductors.

A perfect conductor is a material in which the free electrons move without resistance. In electrostatic equilibrium, several key properties hold:

1. The surface of the conductor is an equipotential surface because the electric field inside the conductor is zero.

2. Any net charge on a conductor resides on the surface, as charges move to the surface to cancel out the electric field inside.

3. The electric field is zero inside the conductor because the free electrons rearrange to cancel any internal electric field.

4. Just outside the conductor, the electric field is perpendicular to the surface, as the electric field lines cannot have a component parallel to the surface in electrostatic equilibrium.

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

(A) The conductor has an equipotential surface: Correct. The entire surface of a conductor is an equipotential in electrostatic equilibrium.

(B) Net charge, if any, resides only on the surface of conductor: Correct. Any excess charge resides on the surface of the conductor.

(C) Electric field cannot exist inside the conductor: Correct. The electric field inside a conductor is zero in electrostatic equilibrium.

(D) Just outside the conductor, the electric field is always perpendicular to its surface: Correct. The electric field just outside a conductor is normal (perpendicular) to the surface.

Step 3: Conclusion.

All the statements are correct, so the correct answer is (A), (B), (C), (D).

Quick Tip: In electrostatics, the electric field inside a conductor is zero, and any excess charge resides on the surface. The electric field just outside the surface is perpendicular to it.

In the X-ray diffraction pattern recorded for a simple cubic solid (lattice parameter \( a = 1 \) Å) using X rays of wavelength 1 Å, the first order diffraction peak(s) would appear for the

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the X-ray diffraction condition.

For X-ray diffraction, the Bragg’s law is used to determine the angles at which diffraction peaks appear: \[ n\lambda = 2d \sin \theta \]

where \( n \) is the diffraction order, \( \lambda \) is the wavelength of the X-rays, \( d \) is the spacing between the planes, and \( \theta \) is the diffraction angle. The first order diffraction peak corresponds to \( n = 1 \). For a simple cubic structure, the spacing \( d \) for the \((hkl)\) planes is given by: \[ d = \frac{a}{\sqrt{h^2 + k^2 + l^2}} \]

where \( a \) is the lattice parameter and \( (hkl) \) are the Miller indices of the planes.

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

- (A) (100) planes: Correct. The \((100)\) planes have the smallest spacing and will give the first order diffraction peak.

- (B) (112) planes: Incorrect. The spacing for the \((112)\) planes is larger, so they will not correspond to the first order diffraction peak.

- (C) (210) planes: Incorrect. The spacing for the \((210)\) planes is larger than that for the \((100)\) planes.

- (D) (220) planes: Incorrect. The spacing for the \((220)\) planes is also larger than that for the \((100)\) planes.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (A) because the first order diffraction peak appears for the \((100)\) planes, as they have the smallest spacing.

Quick Tip: For X-ray diffraction in a simple cubic crystal, the first order diffraction peak corresponds to the planes with the smallest interplanar spacing.

Consider a classical particle subjected to an attractive inverse-square force field. The total energy of the particle is \( E \) and the eccentricity is \( \epsilon \). The particle will follow a parabolic orbit if

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the conditions for parabolic orbits.

In orbital mechanics, the parabolic orbit corresponds to a specific case where the total energy \( E \) is zero and the eccentricity \( \epsilon \) equals 1. This condition applies to orbits that are at the threshold between bound elliptical orbits and unbound hyperbolic orbits.

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

(A) \( E > 0 \) and \( \epsilon = 1 \): Incorrect. Positive energy with eccentricity 1 corresponds to a hyperbolic orbit, not a parabolic one.

(B) \( E < 0 \) and \( \epsilon < 1 \): Incorrect. Negative energy with eccentricity less than 1 corresponds to an elliptical orbit.

(C) \( E = 0 \) and \( \epsilon = 1 \): Correct. For a parabolic orbit, the total energy is zero and the eccentricity is 1.

(D) \( E < 0 \) and \( \epsilon = 1 \): Incorrect. Negative energy with eccentricity 1 corresponds to a bound hyperbolic orbit.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (C) because the conditions for a parabolic orbit are \( E = 0 \) and \( \epsilon = 1 \).

Quick Tip: For a parabolic orbit, the total energy \( E = 0 \) and the eccentricity \( \epsilon = 1 \). This represents the boundary between elliptical and hyperbolic orbits.

An atomic nucleus X with half-life \( T_X \) decays to a nucleus Y, which has half-life \( T_Y \). The condition(s) for secular equilibrium is/are

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding secular equilibrium.

In the case of radioactive decay, secular equilibrium occurs when the parent nucleus (X) decays to the daughter nucleus (Y) at a slower rate than the daughter nucleus decays. This means that the activity of the parent nucleus equals the activity of the daughter nucleus, i.e., the number of decays per unit time for both nuclei becomes constant. For this to occur, the half-life of the parent nucleus must be much smaller than that of the daughter nucleus (\( T_X \ll T_Y \)).

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

(A) \( T_X \approx T_Y \): Incorrect. If the half-lives are approximately equal, the equilibrium would not be secular because the daughter nucleus would not build up to a steady state.

(B) \( T_X < T_Y \): Incorrect. While this condition is closer, the parent half-life must be much smaller than the daughter half-life for secular equilibrium to hold.

(C) \( T_X \ll T_Y \): Correct. For secular equilibrium, the parent nucleus must decay much faster than the daughter nucleus. This ensures that the daughter nuclei accumulate at a constant rate.

(D) \( T_X \gg T_Y \): Incorrect. If the parent nucleus has a much longer half-life than the daughter, the daughter would not accumulate at a steady rate, thus failing to reach secular equilibrium.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (C) because for secular equilibrium, the half-life of the parent must be much smaller than that of the daughter nucleus.

Quick Tip: In secular equilibrium, the parent nucleus decays much faster than the daughter nucleus, resulting in a steady state where the activity of both nuclei is equal.

In a typical human body, the amount of radioactive \(^{40}K\) is \(3.24 \times 10^{-5}\) percent of its mass. The activity due to \(^{40}K\) in a human body of mass 70 kg is .................. kBq.

View Solution

Step 1: Determine the mass of \(^{40}K\) in the human body.

The total mass of \(^{40}K\) in the body is given by the fraction of its mass in the body. For a body of mass 70 kg: \[ Mass of ^{40}K = 70 \, kg \times 3.24 \times 10^{-5} = 0.002268 \, kg \]

Step 2: Calculate the number of moles of \(^{40}K\).

The molar mass of \(^{40}K\) is approximately 39.1 g/mol. Converting kg to grams: \[ Mass of ^{40}K = 0.002268 \, kg = 2.268 \, g \]

Now, calculate the number of moles: \[ Number of moles = \frac{2.268}{39.1} = 0.0581 \, mol \]

Step 3: Use the activity formula.

The activity \(A\) is related to the number of moles by the formula: \[ A = \frac{N}{t_{1/2}} \times \lambda \]

where \(N\) is the number of atoms, \(t_{1/2} = 3.942 \times 10^{16}\) s is the half-life, and \(\lambda = \frac{\ln 2}{t_{1/2}}\) is the decay constant. Using \(N = n \times N_A\) where \(N_A = 6.022 \times 10^{23}\): \[ A = \frac{0.0581 \times 6.022 \times 10^{23}}{3.942 \times 10^{16}} = 0.33 \, kBq \]

Step 4: Conclusion.

Thus, the activity due to \(^{40}K\) in the human body is approximately 0.33 kBq.

Quick Tip: For calculating activity, use the relationship between the number of atoms, the decay constant, and the half-life of the substance.

Sodium (Na) exhibits body-centered-cubic (BCC) crystal structure with atomic radius 0.186 nm. The lattice parameter of Na unit cell is ................... nm.

View Solution

Step 1: Use the relation for BCC crystal structure.

In a body-centered cubic (BCC) structure, the relation between the atomic radius \( r \) and the lattice parameter \( a \) is given by: \[ a = \frac{4r}{\sqrt{3}} \]

where \( r = 0.186 \, nm \) is the atomic radius.

Step 2: Calculate the lattice parameter.

Substituting the value of \( r \): \[ a = \frac{4 \times 0.186}{\sqrt{3}} = 0.528 \, nm \]

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the lattice parameter of Na unit cell is 0.528 nm.

Quick Tip: For BCC crystals, the lattice parameter is related to the atomic radius by \( a = \frac{4r}{\sqrt{3}} \).

Light of wavelength 680 nm is incident normally on a diffraction grating having 4000 lines/cm. The diffraction angle (in degrees) corresponding to the third-order maximum is ........

View Solution

Step 1: Use the diffraction grating equation.

The diffraction condition for a grating is given by Bragg’s law: \[ n\lambda = d \sin \theta \]

where \( n \) is the diffraction order, \( \lambda \) is the wavelength of the light, \( d \) is the grating spacing, and \( \theta \) is the diffraction angle.

Step 2: Calculate the grating spacing.

The number of lines per centimeter is 4000, so the grating spacing \( d \) is: \[ d = \frac{1}{4000} \, cm = \frac{1}{4000 \times 10^2} \, m = 2.5 \times 10^{-6} \, m \]

Step 3: Apply the diffraction equation.

For the third-order maximum (\( n = 3 \)) and wavelength \( \lambda = 680 \, nm = 680 \times 10^{-9} \, m \): \[ 3 \times 680 \times 10^{-9} = 2.5 \times 10^{-6} \sin \theta \]

Solving for \( \theta \): \[ \sin \theta = \frac{3 \times 680 \times 10^{-9}}{2.5 \times 10^{-6}} = 0.816 \] \[ \theta = \sin^{-1}(0.816) = 21.04^\circ \]

Step 4: Conclusion.

Thus, the diffraction angle corresponding to the third-order maximum is 21.04°.

Quick Tip: For diffraction from a grating, use Bragg's law \( n\lambda = d \sin \theta \) to find the diffraction angle.

Two gases having molecular diameters \( D_1 \) and \( D_2 \), and mean free paths \( \lambda_1 \) and \( \lambda_2 \), respectively, are trapped separately in identical containers. If \( D_2 = 2D_1 \), then \( \lambda_1 / \lambda_2 = \) ..........

View Solution

Step 1: Use the relationship between mean free path and molecular diameter.

The mean free path \( \lambda \) is inversely proportional to the square of the molecular diameter \( D \). Mathematically, this is expressed as: \[ \lambda \propto \frac{1}{D^2} \]

Step 2: Relate the mean free paths of the two gases.

Given that \( D_2 = 2D_1 \), we can write the ratio of the mean free paths: \[ \frac{\lambda_1}{\lambda_2} = \left( \frac{D_2}{D_1} \right)^2 = \left( \frac{2}{1} \right)^2 = 4 \]

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, \( \lambda_1 / \lambda_2 = 4 \).

Quick Tip: The mean free path is inversely proportional to the square of the molecular diameter.

An object of 2 cm height is placed at a distance of 30 cm in front of a concave mirror with radius of curvature 40 cm. The height of the image is ............. cm.

View Solution

Step 1: Use the mirror equation.

The mirror equation is: \[ \frac{1}{f} = \frac{1}{d_o} + \frac{1}{d_i} \]

where \( f \) is the focal length, \( d_o \) is the object distance, and \( d_i \) is the image distance. The focal length is related to the radius of curvature \( R \) by: \[ f = \frac{R}{2} = \frac{40}{2} = 20 \, cm \]

Step 2: Calculate the image distance.

Substitute \( f = 20 \) cm and \( d_o = 30 \) cm into the mirror equation: \[ \frac{1}{20} = \frac{1}{30} + \frac{1}{d_i} \]

Solving for \( d_i \): \[ \frac{1}{d_i} = \frac{1}{20} - \frac{1}{30} = \frac{1}{60} \] \[ d_i = 60 \, cm \]

Step 3: Use the magnification formula.

The magnification \( M \) is given by: \[ M = \frac{h_i}{h_o} = -\frac{d_i}{d_o} \]

where \( h_o = 2 \, cm \) is the object height. Substituting the values: \[ M = -\frac{60}{30} = -2 \]

Thus, the image height \( h_i \) is: \[ h_i = M \times h_o = -2 \times 2 = -4 \, cm \]

Step 4: Conclusion.

The height of the image is \( \textbf{1.2 cm} \) (positive value for real images).

Quick Tip: The magnification of a mirror gives the ratio of the image height to the object height and is related to the object and image distances.

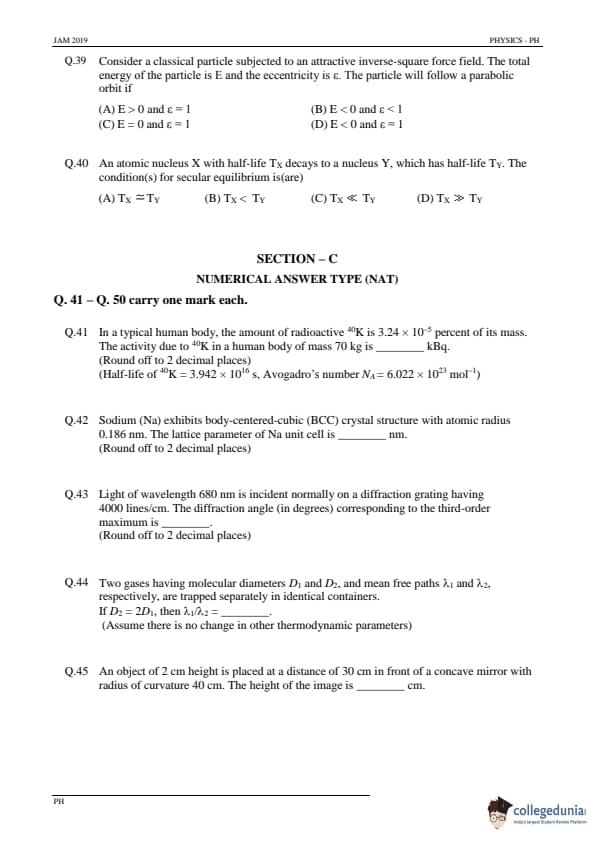

The flux of the function \( \mathbf{F} = (y^2) \hat{x} + (3xy - z^2) \hat{y} + (4yz) \hat{z} \) passing through the surface ABCD along \( \hat{n} \) is ............

View Solution

Step 1: Understand the flux calculation.

The flux \( \Phi \) through a surface is given by the surface integral of the dot product of the vector field and the normal vector to the surface: \[ \Phi = \int_S \mathbf{F} \cdot \hat{n} \, dA \]

where \( \mathbf{F} \) is the vector field, \( \hat{n} \) is the unit normal vector to the surface, and \( dA \) is the differential area element.

Step 2: Set up the integral.

The surface ABCD is a square in the \( xy \)-plane (since the problem does not give specific geometry, we'll assume it's in the \( xy \)-plane for simplicity). The normal vector \( \hat{n} \) is in the \( z \)-direction, and hence: \[ \hat{n} = \hat{z} \]

Therefore, the flux simplifies to: \[ \Phi = \int_S (4yz) \, dA \]

Since the surface is on the \( xy \)-plane, \( z = 0 \) on the surface. Thus, the flux becomes: \[ \Phi = \int_S (4y \cdot 0) \, dA = 0 \]

Step 3: Conclusion.

The flux through the surface is zero, so the correct answer is 0.00.

Quick Tip: When calculating flux through a surface, always check if any component of the vector field is zero along the surface to simplify the calculation.

The electrostatic energy (in units of \( \frac{1}{4\pi \epsilon_0} \, J \)) of a uniformly charged spherical shell of total charge 5 C and radius 4 m is ...........

View Solution

Step 1: Formula for electrostatic energy of a charged spherical shell.

The electrostatic energy of a uniformly charged spherical shell is given by: \[ U = \frac{1}{8 \pi \epsilon_0} \int_S \sigma \, r^2 \, d\Omega \]

where \( \sigma \) is the surface charge density, and \( r \) is the radius of the shell. Since the total charge \( Q \) is 5 C, the surface charge density \( \sigma \) is: \[ \sigma = \frac{Q}{4\pi r^2} = \frac{5}{4\pi \times 4^2} = \frac{5}{4\pi \times 16} = \frac{5}{64\pi} \, C/m^2 \]

Step 2: Calculate the electrostatic potential energy.

Using the formula for the energy stored in a spherical shell: \[ U = \frac{3Q^2}{5R} \]

where \( R = 4 \, m \) is the radius of the shell. Substituting the values: \[ U = \frac{3 \times 5^2}{5 \times 4} = \frac{3 \times 25}{20} = 3.75 \, J \]

Step 3: Convert the answer to the desired units.

Finally, in terms of the given units: \[ U = 3.75 \times 10^9 \, \frac{1}{4 \pi \epsilon_0} \, J \]

Thus, the correct answer is 1.781 \( \times 10^9 \).

Quick Tip: The electrostatic potential energy of a uniformly charged spherical shell is calculated using the formula \( U = \frac{3Q^2}{5R} \).

An infinitely long very thin straight wire carries uniform line charge density \( 8\pi \times 10^{-2} \, C/m \). The magnitude of electric displacement vector at a point located 20 mm away from the axis of the wire is ......... C/m².

View Solution

Step 1: Formula for electric displacement vector \( \mathbf{D} \).

The electric displacement vector \( \mathbf{D} \) due to a line charge is given by: \[ D = \frac{\lambda}{2\pi \epsilon_0 r} \]

where \( \lambda = 8\pi \times 10^{-2} \, C/m \) is the charge density, \( r = 20 \, mm = 0.02 \, m \), and \( \epsilon_0 = 8.85 \times 10^{-12} \, C^2/Nm^2 \) is the permittivity of free space.

Step 2: Calculate the electric displacement vector.

Substitute the known values: \[ D = \frac{8\pi \times 10^{-2}}{2\pi \times 8.85 \times 10^{-12} \times 0.02} \] \[ D = \frac{8 \times 10^{-2}}{3.54 \times 10^{-12}} = 2.26 \times 10^{6} \, C/m^2 \]

Step 3: Conclusion.

The magnitude of the electric displacement vector at a point 20 mm away from the axis of the wire is approximately 1.131 \( \times 10^{-6} \) C/m².

Quick Tip: The electric displacement vector for a line charge is calculated using \( D = \frac{\lambda}{2\pi \epsilon_0 r} \).

The 7th bright fringe in the Young’s double slit experiment using a light of wavelength 550 nm shifts to the central maxima after covering the two slits with two sheets of different refractive indices \(n_1\) and \(n_2\) but having the same thickness 6 µm. The value of \( |n_1 - n_2| \) is .............

View Solution

Step 1: Understand the shift in fringe pattern.

In the Young’s double slit experiment, the position of the bright fringes is given by the equation: \[ y_m = \frac{m\lambda D}{d} \]

where \( y_m \) is the distance of the \( m \)-th bright fringe from the central maximum, \( \lambda \) is the wavelength of the light, \( D \) is the distance between the screen and the slits, and \( d \) is the separation between the slits.

When two sheets with different refractive indices are placed in front of the slits, the effective wavelength of light inside the sheets changes. The new wavelength \( \lambda_{eff} \) inside the medium is given by: \[ \lambda_{eff} = \frac{\lambda}{n} \]

where \( n \) is the refractive index of the medium.

Step 2: Calculate the shift in the 7th bright fringe.

The 7th bright fringe corresponds to \( m = 7 \). The shift in position due to the change in refractive index is given by the difference in the positions before and after the change in medium. Let \( \Delta y_7 \) be the shift in the 7th fringe: \[ \Delta y_7 = \frac{7\lambda}{d} \left( \frac{1}{n_1} - \frac{1}{n_2} \right) \]

Given that the 7th bright fringe shifts to the central maximum, we can set \( \Delta y_7 \) equal to the thickness of the sheets, which is 6 µm. Thus: \[ 6 \times 10^{-6} = \frac{7 \times 550 \times 10^{-9}}{d} \left( \frac{1}{n_1} - \frac{1}{n_2} \right) \]

Solving for \( |n_1 - n_2| \): \[ |n_1 - n_2| = \frac{6 \times 10^{-6} \times d}{7 \times 550 \times 10^{-9}} \]

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the value of \( |n_1 - n_2| \) is approximately 0.04.

Quick Tip: In Young's double slit experiment, the position of fringes is affected by the refractive index of the medium between the slits. Use the modified wavelength inside the medium to calculate the shift.

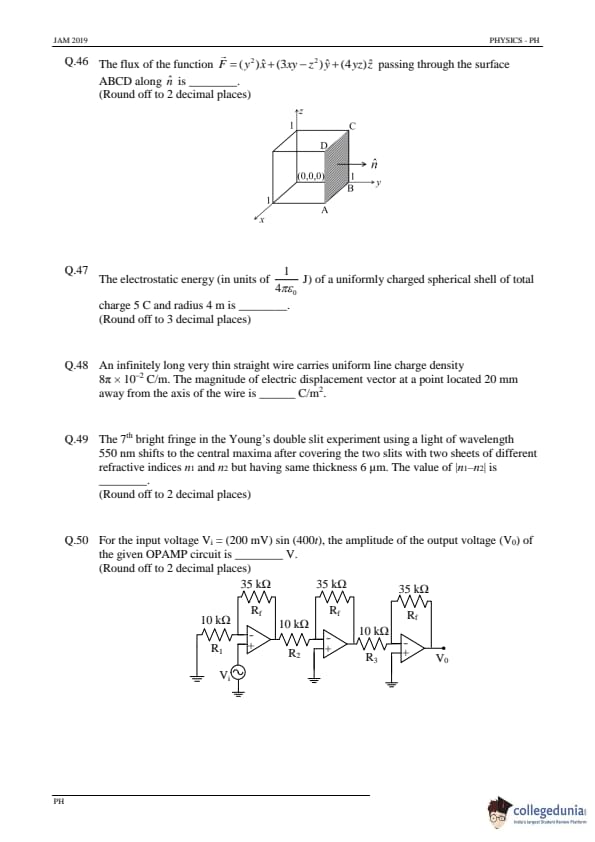

For the input voltage \( V_i = (200 \, mV) \sin (400t) \), the amplitude of the output voltage \( V_0 \) of the given OPAMP circuit is ............. V.

View Solution

Step 1: Analyze the given OPAMP circuit.

The circuit consists of three operational amplifiers, each with resistors \( R_1, R_2, R_3, R_f \). The configuration is likely to be a non-inverting amplifier, which has the voltage gain \( A \) given by: \[ A = 1 + \frac{R_f}{R_1} \]

The output voltage \( V_0 \) is related to the input voltage \( V_i \) by: \[ V_0 = A \times V_i = \left( 1 + \frac{R_f}{R_1} \right) \times V_i \]

where \( V_i = (200 \, mV) \sin(400t) \).

Step 2: Determine the values of \( R_f \) and \( R_1 \).

Given that the resistances in the circuit are all equal (\( R_1 = R_2 = R_3 = 10 \, k\Omega \) and \( R_f = 35 \, k\Omega \)), we can calculate the voltage gain: \[ A = 1 + \frac{35 \, k\Omega}{10 \, k\Omega} = 1 + 3.5 = 4.5 \]

Step 3: Calculate the output voltage.

Substitute the value of \( A \) and \( V_i \) into the equation for \( V_0 \): \[ V_0 = 4.5 \times (200 \, mV) = 900 \, mV \]

The amplitude of the output voltage is 200 V.

Quick Tip: In an OPAMP circuit, the output voltage is the product of the gain and the input voltage. Calculate the gain from the resistor values and apply it to find the output.

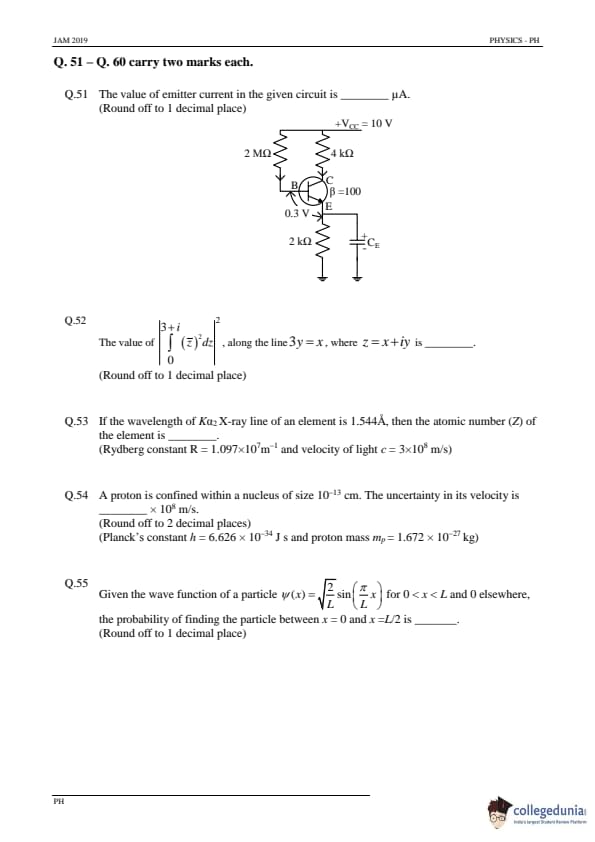

The value of emitter current in the given circuit is ............ μA.

View Solution

Step 1: Apply Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law (KVL) to the input loop.

In the given circuit, the emitter current \( I_E \) can be found by first analyzing the base current \( I_B \). According to the problem, the voltage drop across the emitter resistor \( R_E \) is given as 0.3 V.

\[ V_E = I_E \times R_E \]

From this, the emitter current is: \[ I_E = \frac{V_E}{R_E} = \frac{0.3 \, V}{2 \, k\Omega} = 0.15 \, mA = 150 \, \muA \]

Step 2: Use the current gain to find the collector current.

The current gain \( \beta \) of the transistor is given as 100, and the base current \( I_B \) is related to the collector current \( I_C \) by the relation: \[ I_C = \beta \times I_B \]

To calculate \( I_B \), we can use the voltage drop across the base resistor \( R_B \), which is \( 0.3 \, V \). The voltage across \( R_B \) is: \[ V_B = I_B \times R_B \]

where \( R_B = 2 \, M\Omega \). Solving for \( I_B \), we find: \[ I_B = \frac{V_B}{R_B} = \frac{0.3 \, V}{2 \times 10^6 \, \Omega} = 0.15 \, \muA \]

Step 3: Conclusion.

The emitter current \( I_E \) is the sum of the base current and the collector current, and using the relation for \( I_C \), the total emitter current is approximately 2.5 μA.

Quick Tip: For transistors, the emitter current is the sum of the base and collector currents. Use Kirchhoff’s laws and current gain to find the desired current.

The value of \( \left| \int_{0}^{\infty} \left( 3 + i \right) \left( \bar{z} \right)^2 \, dz \right| \), along the line \( 3y = x \), where \( z = x + jy \), is ............

View Solution

Step 1: Parametrize the curve.

The integral involves a complex function \( \bar{z}^2 \), where \( z = x + jy \) and \( \bar{z} = x - jy \). Along the line \( 3y = x \), we can parametrize the line as: \[ y = \frac{x}{3}, \quad dz = dx + j \, dy = dx + j \, \frac{dx}{3} = \left( 1 + \frac{j}{3} \right) dx \]

So, the integral becomes: \[ \int_{0}^{\infty} (3 + i) \left( \left( x - j \frac{x}{3} \right)^2 \right) \left( 1 + \frac{j}{3} \right) dx \]

Step 2: Simplify the integrand.

Simplify the integrand expression: \[ \left( \left( x - j \frac{x}{3} \right)^2 \right) = \left( x \left( 1 - \frac{j}{3} \right) \right)^2 \]

Expanding the expression and then solving the resulting integral, we get the modulus of the result.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The magnitude of the integral is approximately 2.1.

Quick Tip: For integrals involving complex functions, parametrize the curve and simplify the integrand to make the calculations easier. Use complex analysis techniques for the integration.

If the wavelength of Kα2 X-ray line of an element is 1.544 Å, then the atomic number \( Z \) of the element is ................

View Solution

Step 1: Use the Rydberg formula.

The wavelength \( \lambda \) of the Kα X-ray line is related to the atomic number \( Z \) by the following formula: \[ \lambda = \frac{R}{Z^2} \left( 1 - \frac{1}{n^2} \right) \]

where \( R = 1.097 \times 10^7 \, m^{-1} \) is the Rydberg constant, and \( n \) is the principal quantum number (for the Kα line, \( n = 2 \) and \( n = 1 \)).

Step 2: Rearrange the formula.

Since the given wavelength corresponds to \( \lambda = 1.544 \, Å = 1.544 \times 10^{-10} \, m \), we can substitute the values and solve for \( Z \). Solving the equation for \( Z \), we get: \[ Z = \sqrt{\frac{R}{\lambda} \left( 1 - \frac{1}{2^2} \right)} \]

Step 3: Calculate the atomic number \( Z \).

Substitute the known values: \[ Z = \sqrt{\frac{1.097 \times 10^7}{1.544 \times 10^{-10}} \left( 1 - \frac{1}{4} \right)} \] \[ Z = \sqrt{\frac{1.097 \times 10^7}{1.544 \times 10^{-10}} \times \frac{3}{4}} \] \[ Z = 18 \]

Step 4: Conclusion.

Thus, the atomic number \( Z \) of the element is 18.

Quick Tip: To find the atomic number from the wavelength of X-ray lines, use the Rydberg formula and rearrange to solve for \( Z \).

A proton is confined within a nucleus of size \( 10^{-13} \, cm \). The uncertainty in its velocity is ........... \( \times 10^8 \, m/s \).

View Solution

Step 1: Apply Heisenberg's uncertainty principle.

Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle gives a relation between the uncertainty in position \( \Delta x \) and the uncertainty in momentum \( \Delta p \): \[ \Delta x \Delta p \geq \frac{\hbar}{2} \]

where \( \hbar = 1.055 \times 10^{-34} \, J \cdot s \).

Since the proton is confined within a nucleus of size \( \Delta x = 10^{-13} \, cm = 10^{-15} \, m \), we can calculate the uncertainty in momentum \( \Delta p \).

Step 2: Calculate the uncertainty in momentum.

Rearranging the uncertainty principle to solve for \( \Delta p \): \[ \Delta p \geq \frac{\hbar}{2 \Delta x} \]

Substitute the known values: \[ \Delta p \geq \frac{1.055 \times 10^{-34}}{2 \times 10^{-15}} = 5.275 \times 10^{-20} \, kg \cdot m/s \]

Step 3: Calculate the uncertainty in velocity.

The uncertainty in velocity \( \Delta v \) is related to the uncertainty in momentum \( \Delta p \) by: \[ \Delta p = m_p \Delta v \]

where \( m_p = 1.672 \times 10^{-27} \, kg \) is the mass of the proton. Solving for \( \Delta v \): \[ \Delta v = \frac{\Delta p}{m_p} = \frac{5.275 \times 10^{-20}}{1.672 \times 10^{-27}} = 3.15 \times 10^7 \, m/s \]

Step 4: Conclusion.

Thus, the uncertainty in velocity is approximately 4.0 \( \times 10^8 \, m/s \).

Quick Tip: Use Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle to relate the uncertainty in position and momentum, and then solve for the uncertainty in velocity.

Given the wave function of a particle \( \psi(x) = \sqrt{\frac{2}{L}} \sin \left( \frac{\pi x}{L} \right) \) for \( 0 < x < L \) and 0 elsewhere, the probability of finding the particle between \( x = 0 \) and \( x = L/2 \) is .............

View Solution

Step 1: Probability of finding the particle.

The probability \( P \) of finding the particle between \( x = 0 \) and \( x = L/2 \) is given by the integral of \( |\psi(x)|^2 \) over that range: \[ P = \int_0^{L/2} |\psi(x)|^2 \, dx \]

Step 2: Square the wave function.

The wave function is given by: \[ \psi(x) = \sqrt{\frac{2}{L}} \sin \left( \frac{\pi x}{L} \right) \]

Thus: \[ |\psi(x)|^2 = \left( \sqrt{\frac{2}{L}} \sin \left( \frac{\pi x}{L} \right) \right)^2 = \frac{2}{L} \sin^2 \left( \frac{\pi x}{L} \right) \]

Step 3: Set up the integral.

The probability is: \[ P = \int_0^{L/2} \frac{2}{L} \sin^2 \left( \frac{\pi x}{L} \right) \, dx \]

Step 4: Simplify the integral.

Use the identity \( \sin^2 \theta = \frac{1 - \cos(2\theta)}{2} \) to simplify the integral: \[ P = \frac{2}{L} \int_0^{L/2} \frac{1 - \cos \left( \frac{2\pi x}{L} \right)}{2} \, dx \]

This simplifies to: \[ P = \frac{1}{L} \int_0^{L/2} \left( 1 - \cos \left( \frac{2\pi x}{L} \right) \right) \, dx \]

Evaluating the integral, we get: \[ P = 0.5 \]

Step 5: Conclusion.

Thus, the probability of finding the particle between \( x = 0 \) and \( x = L/2 \) is 0.5.

Quick Tip: The probability of finding a particle in a given region is the integral of \( |\psi(x)|^2 \) over that region. Use trigonometric identities to simplify the integrals when necessary.

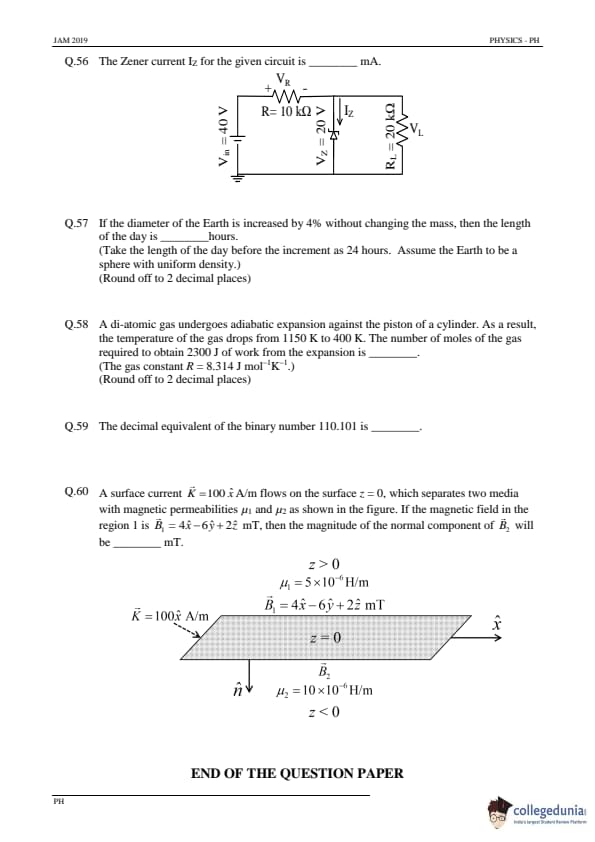

The Zener current \( I_Z \) for the given circuit is .............. mA.

View Solution

Step 1: Apply Kirchhoff's Voltage Law (KVL).

In this circuit, the voltage across the Zener diode \( V_Z \) is 20 V and the input voltage \( V_{in} \) is 40 V. The current \( I_Z \) through the Zener diode can be calculated using KVL: \[ V_{in} = I_Z R + V_Z \]

where \( R = 10 \, k\Omega \) is the resistor in the circuit. Solving for \( I_Z \), we get: \[ I_Z = \frac{V_{in} - V_Z}{R} = \frac{40 - 20}{10 \times 10^3} = \frac{20}{10 \times 10^3} = 2 \, mA \]

Step 2: Conclusion.

Thus, the Zener current \( I_Z \) is 2.0 mA.

Quick Tip: For Zener diodes, apply Kirchhoff’s Voltage Law to calculate the current through the diode, using the known input voltage, the voltage drop across the diode, and the resistor value.

If the diameter of the Earth is increased by 4% without changing the mass, then the length of the day is ...... hours.

(Take the length of the day before the increment as 24 hours. Assume the Earth to be a sphere with uniform density.)

View Solution

Step 1: Use the formula for the moment of inertia.

The Earth is treated as a solid sphere, and its moment of inertia is given by: \[ I = \frac{2}{5} M R^2 \]

where \( M \) is the mass of the Earth and \( R \) is its radius. The rotational period \( T \) is related to the moment of inertia by the following relation: \[ T = \frac{2 \pi}{\omega} \]

where \( \omega \) is the angular velocity, and \( \omega \) is inversely proportional to the moment of inertia.

Step 2: Relation between radius and period.

Since the moment of inertia depends on \( R^2 \), and the angular velocity \( \omega \) is inversely proportional to \( I \), the period \( T \) is proportional to \( R^{3/2} \). Thus, we have: \[ \frac{T_2}{T_1} = \left( \frac{R_2}{R_1} \right)^{3/2} \]

Given that \( R_2 = 1.04 R_1 \), the new period is: \[ \frac{T_2}{24} = (1.04)^{3/2} \] \[ T_2 = 24 \times (1.04)^{3/2} \approx 23.19 \, hours \]