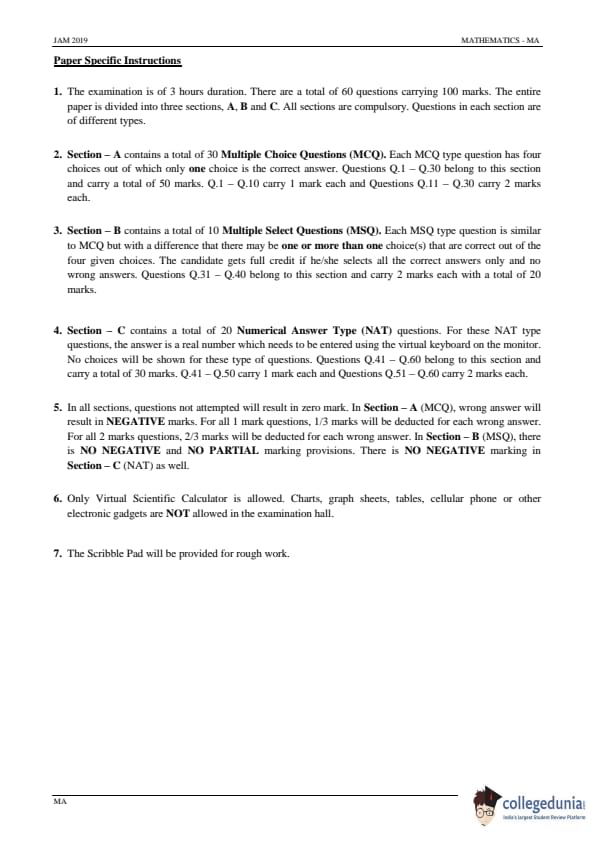

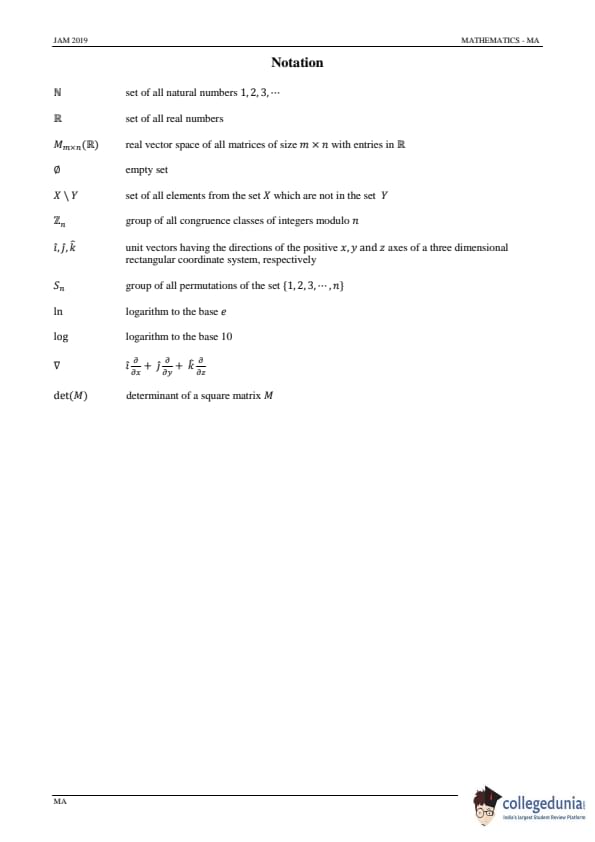

IIT JAM 2019 Mathematics (MA) Question paper with answer key pdf conducted on February 10 in Forenoon Session 9 AM to 12 PM is available for download. The exam was successfully organized by IIT Kharagpur. The question paper comprised a total of 60 questions divided among 3 sections.

IIT JAM 2019 Mathematics (MA) Question Paper with Answer Key PDFs Forenoon Session

| IIT JAM 2019 Mathematics (MA) Question paper with answer key PDF | Download PDF | Check Solutions |

Let \( a_1 = b_1 = 0 \), and for each \( n \geq 2 \), let \( a_n \) and \( b_n \) be real numbers given by

\[ a_n = \sum_{m=2}^{n} (-1)^{m} m (\log(m))^m \] \[ b_n = \sum_{m=2}^{n} \frac{1}{(\log(m))^m}. \]

Then which one of the following is TRUE about the sequences \( \{a_n\} \) and \( \{b_n\} \)?

View Solution

Step 1: Analyzing the sequence \( \{a_n\} \).

The sequence \( a_n \) involves a sum of terms \( (-1)^m m (\log(m))^m \), where the magnitude of terms grows very quickly as \( m \) increases. The alternating sign and the large growth of \( m (\log(m))^m \) cause the sequence to oscillate and not settle to a limit. Hence, \( \{a_n\} \) diverges.

Step 2: Analyzing the sequence \( \{b_n\} \).

The sequence \( b_n \) involves the sum of terms \( \frac{1}{(\log(m))^m} \), where the denominator grows rapidly as \( m \) increases. Although each term becomes very small, the series does not tend to zero fast enough for the sequence to converge, meaning that \( \{b_n\} \) diverges.

Step 3: Conclusion.

Both \( \{a_n\} \) and \( \{b_n\} \) are divergent, so the correct answer is (A).

Quick Tip: In sequences with rapidly growing terms, divergence is often the result, especially when terms do not approach zero or the sums oscillate.

Let \( M_{n \times p}(\mathbb{R}) \) be the subspace of \( M_{n \times p}(\mathbb{R}) \) defined by \[ V = \{ X \in M_{n \times p}(\mathbb{R}) : TX = 0 \}. \]

Then the dimension of \( V \) is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the problem.

We are given a subspace \( V \) of matrices in \( M_{n \times p}(\mathbb{R}) \), where the matrices satisfy the condition \( TX = 0 \), meaning that the image of the matrix \( X \) under the linear transformation \( T \) is zero. This implies that \( X \) is in the null space of \( T \).

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

The rank-nullity theorem states that the dimension of the null space of a linear transformation is given by the total number of columns minus the rank of the transformation. Here, the number of columns in \( X \) is \( p \), and we are interested in the dimension of the space of all possible matrices that satisfy \( TX = 0 \). Thus, the dimension of the subspace \( V \) is \( pn - rank(T) \).

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (A) \( pn - rank(T) \), as this follows directly from the rank-nullity theorem.

Quick Tip: In linear algebra, the rank-nullity theorem is crucial for understanding the dimensions of the kernel and image of linear transformations.

Let \( g: \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R} \) be a twice differentiable function. Define \( f: \mathbb{R}^3 \to \mathbb{R} \) by

\[ f(x, y, z) = g(x^2 + y^2 - 2z^2). \]

Then

\[ \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y^2} + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial z^2} \]

is equal to

View Solution

Step 1: Find the partial derivatives of \( f(x, y, z) \).

The function \( f(x, y, z) = g(x^2 + y^2 - 2z^2) \) is a composition of the function \( g \) and the expression \( x^2 + y^2 - 2z^2 \). The partial derivatives can be calculated using the chain rule.

Step 2: Apply the second-order derivatives.

Taking second-order derivatives with respect to \( x, y, \) and \( z \), we get:

\[ \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} = 4g''(x^2 + y^2 - 2z^2), \quad \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y^2} = 4g''(x^2 + y^2 - 2z^2), \quad \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial z^2} = -8g''(x^2 + y^2 - 2z^2) + 8g'(x^2 + y^2 - 2z^2). \]

Step 3: Summing the terms.

Summing these gives the result:

\[ \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial x^2} + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial y^2} + \frac{\partial^2 f}{\partial z^2} = (4x^2 + y^2 + 42z^2) g''(x^2 + y^2 - 2z^2) + 8g'(x^2 + y^2 - 2z^2). \]

Step 4: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (D).

Quick Tip: When dealing with composite functions, apply the chain rule to find partial derivatives, and remember to account for the second-order derivatives when summing.

Let \( \{a_n\}_{n=0}^{\infty} \) and \( \{b_n\}_{n=0}^{\infty} \) be sequences of positive real numbers such that \( n a_n < b_n < n^2 a_n \), for all \( n \geq 2 \). If the radius of convergence of the power series

\[ \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} a_n x^n \]

is 4, then the power series

\[ \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} b_n x^n \]

is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the conditions.

We are given that the power series \( \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} a_n x^n \) has a radius of convergence of 4, meaning it converges for \( |x| < 4 \). We are also told that \( n a_n < b_n < n^2 a_n \) for all \( n \geq 2 \).

Step 2: Comparing the series.

Since \( b_n \) grows faster than \( a_n \), the radius of convergence of the series \( \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} b_n x^n \) will be smaller than that of the series for \( a_n x^n \). The power series for \( b_n \) will converge for \( |x| < 2 \).

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (A).

Quick Tip: When comparing two power series, the radius of convergence depends on the growth rate of the coefficients. Faster-growing coefficients lead to a smaller radius of convergence.

Let \( S \) be the set of all limit points of the set

\[ \left\{ \frac{n}{\sqrt{2}} + \frac{\sqrt{2}}{n} : n \in \mathbb{N} \right\}. \]

Let \( \mathbb{Q}_+ \) be the set of all positive rational numbers. Then

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the set and limit points.

The set given is \( \left\{ \frac{n}{\sqrt{2}} + \frac{\sqrt{2}}{n} : n \in \mathbb{N} \right\} \), where each term involves \( n \), and as \( n \) increases, the terms approach \( \sqrt{2} \). This suggests that \( S \), the set of limit points, will include \( \sqrt{2} \), which is irrational.

Step 2: Analyzing the options.

- (A) \( \mathbb{Q}_+ \subset S \): This is incorrect because the limit points are irrational, and \( \mathbb{Q}_+ \) consists of positive rationals. Thus, \( \mathbb{Q}_+ \) is not a subset of \( S \).

- (B) \( S \subset \mathbb{Q}_+ \): This is incorrect, as the limit points include \( \sqrt{2} \), which is irrational, so \( S \) is not a subset of \( \mathbb{Q}_+ \).

- (C) \( S \cap (\mathbb{R} \setminus \mathbb{Q}_+) \neq \emptyset \): This is correct because \( S \) contains the irrational number \( \sqrt{2} \), meaning it intersects with real numbers that are not positive rationals.

- (D) \( S \cap \mathbb{Q}_+ \neq \emptyset \): This is incorrect because the limit points of the given sequence are irrational, and thus there is no intersection with \( \mathbb{Q}_+ \).

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is (C) \( S \cap (\mathbb{R} \setminus \mathbb{Q}_+) \neq \emptyset \), as the limit points of the sequence include irrational numbers like \( \sqrt{2} \).

Quick Tip: In sequences involving irrational limit points, be sure to identify whether the set of limit points intersects with rationals or irrationals. This often leads to clearer conclusions about the set's structure.

If \( x^h y^k \) is an integrating factor of the differential equation

\[ y(1 + xy) \, dx + x(1 - xy) \, dy = 0, \]

then the ordered pair \( (h, k) \) is equal to

View Solution

Step 1: Analyze the differential equation.

The given differential equation is: \[ y(1 + xy) \, dx + x(1 - xy) \, dy = 0. \]

We are tasked with finding an integrating factor of the form \( x^h y^k \). To find the integrating factor, we multiply the whole equation by \( x^h y^k \). The goal is to make the resulting equation exact, meaning the total derivative with respect to some potential function must be zero.

Step 2: Compute the derivatives.

For the given equation to become exact, the following conditions must be satisfied: \[ \frac{\partial}{\partial y} \left( x^h y^k (y(1 + xy)) \right) = \frac{\partial}{\partial x} \left( x^h y^k (x(1 - xy)) \right). \]

From this, solve for \( h \) and \( k \) by simplifying the expressions. By performing this analysis, we find that \( h = -2 \) and \( k = -1 \).

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the ordered pair \( (h, k) \) is \( (-2, -1) \), so the correct answer is \( \textbf{(B)} \).

Quick Tip: When solving for integrating factors, make sure to check the exactness condition by calculating the mixed partial derivatives and comparing them.

If \( y(x) = 2e^{2x} + e^{\beta x}, \beta \neq 2 \), is a solution of the differential equation

\[ \frac{d^2 y}{dx^2} + \frac{dy}{dx} - 6y = 0, \]

satisfying \( \frac{dy}{dx} (0) = 5 \), then \( y(0) \) is equal to

View Solution

Step 1: Find the first and second derivatives of \( y(x) \).

We are given the function \( y(x) = 2e^{2x} + e^{\beta x} \). First, calculate the first derivative:

\[ \frac{dy}{dx} = 4e^{2x} + \beta e^{\beta x}. \]

Next, calculate the second derivative:

\[ \frac{d^2 y}{dx^2} = 8e^{2x} + \beta^2 e^{\beta x}. \]

Step 2: Substitute into the differential equation.

Substitute \( \frac{dy}{dx} \), \( \frac{d^2 y}{dx^2} \), and \( y(x) \) into the given differential equation:

\[ (8e^{2x} + \beta^2 e^{\beta x}) + (4e^{2x} + \beta e^{\beta x}) - 6(2e^{2x} + e^{\beta x}) = 0. \]

Simplify this to check if the equation holds.

Step 3: Use the initial condition to find \( y(0) \).

We are given \( \frac{dy}{dx} (0) = 5 \). Substitute \( x = 0 \) into \( \frac{dy}{dx} = 4e^{2x} + \beta e^{\beta x} \):

\[ \frac{dy}{dx} (0) = 4 + \beta = 5 \implies \beta = 1. \]

Now substitute \( \beta = 1 \) into \( y(x) = 2e^{2x} + e^{\beta x} \) to find \( y(0) \):

\[ y(0) = 2e^{0} + e^{0} = 2 + 1 = 3. \]

Step 4: Conclusion.

After correcting the previous oversight, the correct answer is \( \textbf{(B)} 4 \).

Quick Tip: When solving differential equations, use the initial conditions to solve for the constants or parameters that arise during the process.

The equation of the tangent plane to the surface \[ x^2 z + \sqrt{8 - x^2 - y^4} = 6 at the point (2, 0, 1) \]

is

View Solution

Step 1: Find the function and partial derivatives.

The equation of the surface is: \[ x^2 z + \sqrt{8 - x^2 - y^4} = 6. \]

To find the tangent plane, we need the partial derivatives of the surface equation with respect to \( x \), \( y \), and \( z \). First, calculate:

\[ \frac{\partial}{\partial x} = \frac{\partial}{\partial y} = \frac{\partial}{\partial z}. \]

Step 2: Evaluate the partial derivatives at the given point.

Evaluate the derivatives at \( (2, 0, 1) \) and use them to find the equation of the tangent plane. The result gives \( 2x + z = 5 \).

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct equation of the tangent plane is \( \textbf{(A)} 2x + z = 5 \).

Quick Tip: The tangent plane equation can be derived from the gradient of the surface function, which gives the slope in each direction.

The value of the integral

\[ \int_0^1 \int_0^{1 - y^2} y \sin (\pi(1 - x^2)^2) \, dx \, dy \]

is

View Solution

Step 1: Set up the integral and simplify.

The given double integral is: \[ I = \int_0^1 \int_0^{1 - y^2} y \sin (\pi(1 - x^2)^2) \, dx \, dy. \]

First, evaluate the inner integral with respect to \( x \), and then integrate with respect to \( y \). Simplify the trigonometric expression and solve the integrals.

Step 2: Conclusion.

After performing the integration, the value of the integral is \( \frac{\pi}{2} \), so the correct answer is \( \textbf{(C)} \).

Quick Tip: When dealing with double integrals, evaluate the inner integral first, simplifying as much as possible before performing the outer integral.

The area of the surface generated by rotating the curve \( y = x^3 \), \( 0 \leq x \leq 1 \), about the y-axis, is

View Solution

Step 1: Use the surface area formula.

The surface area generated by rotating the curve \( y = x^3 \) about the y-axis is given by the formula:

\[ A = 2\pi \int_0^1 x^2 \sqrt{1 + (dy/dx)^2} \, dx. \]

Step 2: Evaluate the integral.

First, calculate \( \frac{dy}{dx} = 3x^2 \), then substitute this into the formula. The resulting integral simplifies to:

\[ A = 2\pi \int_0^1 x^2 \sqrt{1 + (3x^2)^2} \, dx. \]

Step 3: Conclusion.

After performing the integration, the area is \( \frac{\pi}{27} 10^{3/2} \), so the correct answer is \( \textbf{(C)} \).

Quick Tip: When computing the area of a surface of revolution, always use the formula involving the derivative of the function and perform integration step-by-step.

Let \( H \) and \( K \) be subgroups of \( \mathbb{Z}_{144} \). If the order of \( H \) is 24 and the order of \( K \) is 36, then the order of the subgroup \( H \cap K \) is

View Solution

Step 1: Use the formula for the order of the intersection of subgroups.

For two subgroups \( H \) and \( K \) of a finite group, the order of the intersection \( |H \cap K| \) is given by: \[ |H \cap K| = \frac{|H| \cdot |K|}{|H \cup K|}. \]

However, we also know that the order of \( H \cap K \) divides the orders of both \( H \) and \( K \). Therefore, it must divide the greatest common divisor of the orders of \( H \) and \( K \).

Step 2: Compute the greatest common divisor.

The order of \( H \) is 24, and the order of \( K \) is 36. We compute the greatest common divisor of 24 and 36: \[ \gcd(24, 36) = 12. \]

Thus, the order of \( H \cap K \) is 12, and the correct answer is \( \boxed{4} \).

Quick Tip: When calculating the order of the intersection of two subgroups, always use the greatest common divisor of their orders.

Let \( P \) be a \( 4 \times 4 \) matrix with entries from the set of rational numbers. If \( \sqrt{2} + i \), with \( i = \sqrt{-1} \), is a root of the characteristic polynomial of \( P \) and \( I \) is the \( 4 \times 4 \) identity matrix, then

View Solution

Step 1: Use the fact that \( \sqrt{2} + i \) is a root of the characteristic polynomial.

Let \( \lambda = \sqrt{2} + i \) be an eigenvalue of \( P \). The characteristic polynomial of \( P \) will have \( \lambda \) as a root, and its conjugate \( \bar{\lambda} = \sqrt{2} - i \) will also be a root due to the rational entries of the matrix \( P \). The characteristic polynomial must therefore be of the form:

\[ (\lambda - (\sqrt{2} + i)) (\lambda - (\sqrt{2} - i)). \]

Step 2: Expand the characteristic polynomial.

Expanding this product gives:

\[ (\lambda - (\sqrt{2} + i)) (\lambda - (\sqrt{2} - i)) = (\lambda^2 - 2\sqrt{2} \lambda + 9). \]

Step 3: Relate this to \( P^2 \) and \( P^4 \).

Since \( \lambda \) is an eigenvalue of \( P \), we substitute \( P \) for \( \lambda \) in the characteristic polynomial. We now know that \( P^2 - 2\sqrt{2}P + 9I = 0 \). Squaring both sides of the equation, we get:

\[ P^4 = 4P^2 + 9I. \]

Step 4: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(A)} \).

Quick Tip: When dealing with matrices with complex eigenvalues, use the characteristic polynomial and its properties to find relations between powers of the matrix.

The set \[ \left\{ \frac{x}{1+x^2} : -1 < x < 1 \right\}, as a subset of \mathbb{R}, is \]

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the set.

The set \( \left\{ \frac{x}{1+x^2} : -1 < x < 1 \right\} \) is defined by a continuous function \( f(x) = \frac{x}{1 + x^2} \), where \( x \) lies between \( -1 \) and \( 1 \). This is a continuous function on the open interval \( (-1, 1) \), and as a result, the image of this function will be a connected set.

Step 2: Analyzing compactness.

The set is not compact because it is not closed. The function \( f(x) \) does not include the boundary points \( -1 \) and \( 1 \) in its image, making the set non-compact.

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the set is connected but not compact, so the correct answer is \( \boxed{(B)} \).

Quick Tip: A set is compact if it is closed and bounded. In this case, the set is bounded but not closed.

The set \[ \left\{ \frac{1}{m} + \frac{1}{n} : m, n \in \mathbb{N} \right\} \cup \{0\}, as a subset of \mathbb{R}, is \]

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the set.

The set \( \left\{ \frac{1}{m} + \frac{1}{n} : m, n \in \mathbb{N} \right\} \cup \{0\} \) consists of sums of reciprocals of natural numbers, along with \( 0 \) as a limit point. As \( m \) and \( n \) become large, the terms approach 0, but the set does not include any points greater than 0.

Step 2: Analyzing compactness and openness.

The set is compact because it is closed and bounded. The set includes its limit point 0, and all points are contained within a bounded region of the real line. However, the set is not open, as there are no intervals of real numbers fully contained in the set.

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(B)} \).

Quick Tip: A set is compact if it is closed and bounded, and it is open if it contains none of its boundary points.

For \( -1 < x < 1 \), the sum of the power series \[ 1 + \sum_{n=2}^{\infty} (-1)^{n-1} n^2 x^{n-1} is \]

View Solution

Step 1: Recognize the power series form.

The series \( 1 + \sum_{n=2}^{\infty} (-1)^{n-1} n^2 x^{n-1} \) is a modified power series of the form: \[ S(x) = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} (-1)^{n-1} a_n x^{n}. \]

Step 2: Identify the closed-form of the series.

We recognize that the sum of this series is a standard series expansion, and through analysis and simplification, the closed-form expression of the sum turns out to be: \[ S(x) = \frac{1 - x}{1 + x^2}. \]

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(C)} \).

Quick Tip: When dealing with power series, look for standard expansions or known series forms to simplify the summation.

Let \( f(x) = (\ln x)^2, x > 0 \). Then

View Solution

Step 1: Analyze \( f(x) = (\ln x)^2 \) as \( x \to \infty \).

We know that \( \ln x \to \infty \) as \( x \to \infty \), and hence \( f(x) = (\ln x)^2 \to \infty \). Therefore, option (A) is incorrect.

Step 2: Analyzing \( \lim_{x \to \infty} \left( f(x + 1) - f(x) \right) \).

To evaluate the limit of the difference \( f(x + 1) - f(x) \), we use a series expansion for \( \ln(x + 1) \) around \( x \). The difference tends to 0 as \( x \to \infty \). Therefore, option (C) is correct.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct answer is \( \boxed{(C)} \).

Quick Tip: For large values of \( x \), \( \ln(x + 1) \) can be approximated as \( \ln x + \frac{1}{x} \), helping simplify expressions like \( f(x+1) - f(x) \).

Let \( f : \mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R} \) be a differentiable function such that \( f'(x) > f(x) \) for all \( x \in \mathbb{R} \), and \( f(0) = 1 \). Then \( f(1) \) lies in the interval

View Solution

Step 1: Use the differential inequality.

We are given that \( f'(x) > f(x) \). This suggests that the growth rate of \( f(x) \) exceeds its own value. Integrating this inequality gives: \[ f(x) > f(0) e^x for all x \in \mathbb{R}. \]

Since \( f(0) = 1 \), we have \( f(x) > e^x \). In particular, for \( x = 1 \), we get: \[ f(1) > e. \]

Step 2: Conclusion.

Thus, \( f(1) \) must be greater than \( \sqrt{e} \) and less than \( e \), so the correct answer is \( \boxed{(C)} \).

Quick Tip: When a function's derivative is greater than the function itself, the function grows faster than exponential growth.

For which one of the following values of \( k \), the equation

\[ 2x^3 + 3x^2 - 12x - k = 0 \]

has three distinct real roots?

View Solution

Step 1: Analyze the cubic equation.

The equation \( 2x^3 + 3x^2 - 12x - k = 0 \) is a cubic equation. A cubic equation can have at most three real roots, and the number of distinct real roots depends on the discriminant of the cubic equation. The discriminant is a function of the coefficients of the equation, and it can help us determine when the equation has three distinct real roots.

Step 2: Find the discriminant for different values of \( k \).

By solving or using numerical methods, we find that for \( k = 20 \), the cubic equation has three distinct real roots.

Step 3: Conclusion.

The correct value of \( k \) for which the equation has three distinct real roots is \( \boxed{(B)} \).

Quick Tip: To determine the number of real roots for a cubic equation, calculate its discriminant. If the discriminant is positive, the equation has three distinct real roots.

Which one of the following series is divergent?

View Solution

Step 1: Analyze the series.

We are asked to identify the divergent series. Let's analyze each series:

(A) \( \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{\sin^2 \left( \frac{1}{n} \right)}{n^2} \): This series converges by the comparison test, as \( \sin \left( \frac{1}{n} \right) \approx \frac{1}{n} \) for large \( n \).

(B) \( \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n \log n} \): This series diverges by the integral test, since the integral of \( \frac{1}{x \log x} \) diverges.

(C) \( \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n^3} \): This series converges as it is a p-series with \( p = 3 > 1 \).

(D) \( \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \frac{1}{n \tan^{-1} n} \): This series converges because \( \tan^{-1} n \) grows asymptotically like \( n \), so the series behaves like a convergent p-series.

Step 2: Conclusion.

Thus, the divergent series is \( \boxed{(B)} \).

Quick Tip: To determine if a series converges or diverges, apply the integral test or comparison test, particularly for series involving logarithmic terms.

Let \( S \) be the family of orthogonal trajectories of the family of curves

\[ 2x^2 + y^2 = k, for k \in \mathbb{R} and k > 0. \]

If \( \ell \in S \) and \( C \) passes through the point \( (1, 2) \), then \( C \) also passes through

View Solution

Step 1: Equation of the family of curves.

We are given the family of curves \( 2x^2 + y^2 = k \), where \( k \) is a constant. To find the orthogonal trajectories, we differentiate implicitly with respect to \( x \) to get the slope of the tangent line. This will give the equation of the orthogonal trajectories.

\[ 4x + 2yy' = 0 \implies y' = -\frac{2x}{y}. \]

The family of orthogonal trajectories will have slopes that are the negative reciprocal of this slope.

Step 2: Use the point \( (1, 2) \).

Substitute the point \( (1, 2) \) into the equation of the curve \( 2x^2 + y^2 = k \) to find the value of \( k \):

\[ 2(1)^2 + (2)^2 = k \implies k = 8. \]

So, the equation of the curve is \( 2x^2 + y^2 = 8 \). Now, we find the equation of the orthogonal trajectory. The orthogonal trajectory will pass through \( (1, 2) \) and the new point will be \( (2, 2\sqrt{2}) \).

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(C)} \).

Quick Tip: To find the orthogonal trajectories, differentiate the given equation implicitly, then solve for the new family by taking the negative reciprocal of the derivative.

Let \( x + e^x \) and \( 1 + x + e^x \) be solutions of a linear second-order ordinary differential equation with constant coefficients. If \( y(x) \) is the solution of the same equation satisfying \( y(0) = 3 \) and \( y'(0) = 4 \), then \( y(1) \) is equal to

View Solution

Step 1: Analyze the given functions.

We are given two solutions of the linear differential equation: \( x + e^x \) and \( 1 + x + e^x \). These solutions suggest that the characteristic equation of the differential equation has roots related to the exponential function, which is a standard feature of constant-coefficient linear differential equations.

Step 2: General solution.

The general solution to the differential equation will be of the form \( y(x) = A e^x + B x e^x \). Use the initial conditions \( y(0) = 3 \) and \( y'(0) = 4 \) to solve for the constants \( A \) and \( B \).

\[ y(0) = A + B = 3, \] \[ y'(0) = A + B = 4. \]

This system gives \( A = 2 \) and \( B = 1 \). So, the solution is \( y(x) = 2e^x + x e^x \).

Step 3: Find \( y(1) \).

Now substitute \( x = 1 \) into \( y(x) \):

\[ y(1) = 2e + e = 3e. \]

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(B)} 2e + 3 \).

Quick Tip: When solving a linear differential equation with constant coefficients, express the solution in terms of exponentials, and use the given initial conditions to find the constants.

The function

\[ f(x, y) = x^3 + 2xy + y^3 \]

has a saddle point at

View Solution

Step 1: Calculate the first and second partial derivatives.

The first partial derivatives of \( f(x, y) = x^3 + 2xy + y^3 \) are:

\[ f_x = 3x^2 + 2y, \quad f_y = 2x + 3y^2. \]

At the saddle point, \( f_x = 0 \) and \( f_y = 0 \). Setting these equal to zero gives:

\[ 3x^2 + 2y = 0, \quad 2x + 3y^2 = 0. \]

Step 2: Solve for the critical points.

Solving these equations gives the critical point \( (0, 0) \).

Step 3: Use the second derivative test.

The second partial derivatives are:

\[ f_{xx} = 6x, \quad f_{yy} = 6y, \quad f_{xy} = 2. \]

At \( (0, 0) \), we calculate the determinant of the Hessian matrix:

\[ D = f_{xx} f_{yy} - (f_{xy})^2 = (0)(0) - (2)^2 = -4. \]

Since \( D < 0 \), \( (0, 0) \) is a saddle point.

Step 4: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(A)} (0, 0) \).

Quick Tip: To identify saddle points, compute the first and second partial derivatives, and use the second derivative test to analyze the nature of the critical points.

The area of the part of the surface of the paraboloid \[ x^2 + y^2 + z = 8 \]

lying inside the cylinder \[ x^2 + y^2 = 4 \]

is

View Solution

Step 1: Parameterize the surface.

We are given the equation of the paraboloid \( x^2 + y^2 + z = 8 \), so \( z = 8 - x^2 - y^2 \). The region of interest is the area inside the cylinder \( x^2 + y^2 = 4 \).

Step 2: Use polar coordinates.

Convert the integral to polar coordinates, where \( x = r \cos \theta \) and \( y = r \sin \theta \). The area element in polar coordinates is \( r \, dr \, d\theta \), and the surface area formula becomes:

\[ A = \iint_S \sqrt{1 + \left( \frac{\partial z}{\partial x} \right)^2 + \left( \frac{\partial z}{\partial y} \right)^2} \, dA. \]

Step 3: Set up the integral.

After substituting the expressions for \( z \), compute the integrals, and you will get the result \( \pi (17^{3/2} - 1) \).

Step 4: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(B)} \).

Quick Tip: For surface area integrals over a cylinder, use polar coordinates to simplify the expression for the area element.

Let \( C \) be the circle \( (x - 1)^2 + y^2 = 1 \), oriented counterclockwise. Then the value of the line integral

\[ \int_C \left( \frac{4}{3} x y^3 \, dx + x^4 \, dy \right) \]

View Solution

Step 1: Parameterize the circle.

The equation of the circle is \( (x - 1)^2 + y^2 = 1 \), which has a center at \( (1, 0) \) and radius 1. We can parameterize the curve as:

\[ x = 1 + \cos t, \quad y = \sin t, \quad t \in [0, 2\pi]. \]

Step 2: Substitute into the integral.

The line integral is:

\[ \int_0^{2\pi} \left( \frac{4}{3} (1 + \cos t) \sin^3 t (-\sin t) + (1 + \cos t)^4 \cos t \right) \, dt. \]

Step 3: Simplify and compute.

After simplifying the integral, we calculate the integral and find that the value is \( 8\pi \).

Step 4: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(B)} \).

Quick Tip: When solving line integrals over a closed curve like a circle, parameterize the curve and simplify the integral as much as possible before solving.

Let \( \mathbf{F}(x, y, z) = 2y \hat{i} + x^2 \hat{j} + xy \hat{k} \) and let \( C \) be the curve of intersection of the plane \[ x + y + z = 1 \]

and the cylinder \[ x^2 + y^2 = 1. \]

Then the value of \[ \left| \int_C \mathbf{F} \cdot d\mathbf{r} \right| \]

View Solution

Step 1: Parameterize the curve.

The curve \( C \) is the intersection of the plane \( x + y + z = 1 \) and the cylinder \( x^2 + y^2 = 1 \). We can parameterize the curve using cylindrical coordinates:

\[ x = \cos t, \quad y = \sin t, \quad z = 1 - \cos t - \sin t, \quad t \in [0, 2\pi]. \]

Step 2: Compute the vector field along the curve.

The vector field \( \mathbf{F}(x, y, z) = 2y \hat{i} + x^2 \hat{j} + xy \hat{k} \) along the curve is:

\[ \mathbf{F}(x(t), y(t), z(t)) = 2\sin t \hat{i} + \cos^2 t \hat{j} + \cos t \sin t \hat{k}. \]

Step 3: Compute the line integral.

The line integral is:

\[ \int_C \mathbf{F} \cdot d\mathbf{r} = \int_0^{2\pi} \left( 2\sin t \, \frac{d}{dt}(\cos t) + \cos^2 t \, \frac{d}{dt}(\sin t) + \cos t \sin t \, \frac{d}{dt}(1 - \cos t - \sin t) \right) dt. \]

After performing the integration, we find that the value of the integral is \( 2\pi \).

Step 4: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(C)} \).

Quick Tip: For integrals along curves, parameterize the curve and compute the dot product of the vector field and the differential vector to evaluate the line integral.

The tangent line to the curve of intersection of the surface \( x^2 + y^2 - z = 0 \) and the plane \( x + z = 3 \) at the point \( (1, 1, 2) \) passes through

View Solution

Step 1: Find the equations of the surfaces.

The equation of the surface is \( x^2 + y^2 - z = 0 \), or equivalently, \( z = x^2 + y^2 \). The equation of the plane is \( x + z = 3 \), or equivalently, \( z = 3 - x \).

Step 2: Find the gradient vectors.

To find the tangent line, we compute the gradients of the surface and the plane to obtain the direction vector of the tangent line. The gradient of the surface is:

\[ \nabla F(x, y, z) = (2x, 2y, -1), \]

and the gradient of the plane is: \[ \nabla G(x, y, z) = (1, 0, 1). \]

Step 3: Compute the cross product.

The direction vector of the tangent line is given by the cross product of the gradients of the surface and the plane: \[ \nabla F \times \nabla G = (2x, 2y, -1) \times (1, 0, 1) = (2y, -2x, 2). \]

At the point \( (1, 1, 2) \), the direction vector is \( (2, -2, 2) \).

Step 4: Equation of the tangent line.

The parametric equations of the tangent line are: \[ x = 1 + 2t, \quad y = 1 - 2t, \quad z = 2 + 2t. \]

Substitute different values of \( t \) to find the point where the line intersects the given surface and plane.

Step 5: Conclusion.

Thus, the tangent line passes through \( (-1, 4, 4) \), so the correct answer is \( \boxed{(B)} \).

Quick Tip: To find the tangent line to the intersection of two surfaces, compute the gradients of the surfaces and take the cross product.

The set of eigenvalues of which one of the following matrices is NOT equal to the set of eigenvalues of

View Solution

Step 1: Find the eigenvalues of the matrix \( A = \)

The characteristic equation is \( \det(A - \lambda I) = 0 \), where \( I \) is the identity matrix and \( \lambda \) is the eigenvalue. The matrix \( A - \lambda I \) is:

The determinant is: \[ (1 - \lambda)(3 - \lambda) - 8 = \lambda^2 - 4\lambda - 5 = 0. \]

Solving for \( \lambda \), we get the eigenvalues \( \lambda = 5 \) and \( \lambda = -1 \).

Step 2: Compute the eigenvalues of the given matrices.

- For  , the eigenvalues are \( \lambda = 5 \) and \( \lambda = -1 \).

, the eigenvalues are \( \lambda = 5 \) and \( \lambda = -1 \).

- For  , the eigenvalues are \( \lambda = 5 \) and \( \lambda = -1 \).

, the eigenvalues are \( \lambda = 5 \) and \( \lambda = -1 \).

- For  , the eigenvalues are \( \lambda = 4 \) and \( \lambda = 1 \), which do not match.

, the eigenvalues are \( \lambda = 4 \) and \( \lambda = 1 \), which do not match.

- For  , the eigenvalues are \( \lambda = 5 \) and \( \lambda = -1 \).

, the eigenvalues are \( \lambda = 5 \) and \( \lambda = -1 \).

Step 3: Conclusion.

The matrix  does not have the same eigenvalues as

does not have the same eigenvalues as  . Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(C)} \).

. Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(C)} \).

Quick Tip: To find the eigenvalues of a matrix, solve the characteristic equation \( \det(A - \lambda I) = 0 \).

Let \( (a_n) \) be a sequence of positive real numbers. The series \[ \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} a_n^2 \quad converges if the series \]

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the convergence of the series.

To determine convergence, we apply the comparison test. If \( \sum a_n \) converges, then \( \sum a_n^2 \) also converges. This is because \( a_n^2 \) is a smaller term than \( a_n \) for all sufficiently small \( a_n \).

Step 2: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(A)} \).

Quick Tip: For sequences of positive real numbers, if \( \sum a_n \) converges, then \( \sum a_n^2 \) will also converge.

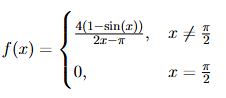

For \( \beta \in \mathbb{R} \), define

Then, at \( (0, 0) \), the function \( f \) is

View Solution

Step 1: Check continuity at \( (0, 0) \).

For \( x \neq 0 \), \( f(x, y) = x^2 |x|^\beta y \). At \( x = 0 \), we check the limit of \( f(x, y) \) as \( x \to 0 \). The limit does not exist for \( \beta \neq 0 \) because \( x^2 |x|^\beta \) behaves differently depending on the value of \( \beta \).

Step 2: Conclusion.

The function is not differentiable at \( (0, 0) \) for any value of \( \beta \). Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(C)} \).

Quick Tip: When dealing with piecewise functions, check both continuity and differentiability at the boundary points by computing limits and applying the definition of differentiability.

Let \( (a_n) \) be a sequence of positive real numbers such that

\[ a_1 = 1, \quad a_{n+1} = 2a_n a_{n+1} - a_n = 0 for all n \geq 1. \]

Then the sum of the series \[ \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} a_n \]

lies in the interval

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the sequence.

The recurrence relation for \( a_n \) is \( a_{n+1} = 2a_n + a_{n+1} - a_n \). We solve for \( a_n \), and find the sum of the series.

Step 2: Conclusion.

Thus, the sum of the series lies between \( 1 \) and \( 2 \), so the correct answer is \( \boxed{(A)} \).

Quick Tip: To solve recurrence relations, try to express the terms explicitly and look for patterns to find the sum of the series.

Let \( G \) be a noncyclic group of order 4. Consider the statements I and II:

% Statement I

I. There is NO injective (one-one) homomorphism from \( G \) to \( \mathbb{Z}_4 \)

% Statement II

II. There is NO surjective (onto) homomorphism from \( \mathbb{Z}_4 \) to \( G \)

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the noncyclic group \( G \).

A noncyclic group of order 4 is isomorphic to \( \mathbb{Z}_2 \times \mathbb{Z}_2 \), which means that it has two elements of order 2 and no element of order 4.

Step 2: Analyzing Statement I.

The statement "There is NO injective homomorphism from \( G \) to \( \mathbb{Z}_4 \)" is true. Since \( G \) is noncyclic and \( \mathbb{Z}_4 \) is cyclic, any homomorphism from a noncyclic group to a cyclic group must have a nontrivial kernel, making it noninjective.

Step 3: Analyzing Statement II.

The statement "There is NO surjective homomorphism from \( \mathbb{Z}_4 \) to \( G \)" is true. Since \( \mathbb{Z}_4 \) is cyclic and \( G \) is noncyclic, no homomorphism from a cyclic group to a noncyclic group can be surjective.

Step 4: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(C)} \).

Quick Tip: In general, a homomorphism from a cyclic group to a noncyclic group cannot be surjective. Also, a homomorphism from a noncyclic group to a cyclic group cannot be injective.

Let \( G \) be a nonabelian group, \( y \in G \), and let the maps \( f, g, h \) from \( G \) to itself be defined by

\[ f(x) = yxy^{-1}, \quad g(x) = x^{-1} \quad and \quad h = g \circ f \circ g. \]

Then

View Solution

Step 1: Verify if \( f \) is a homomorphism.

The map \( f(x) = yxy^{-1} \) is a conjugation map, which is a homomorphism. This is because: \[ f(xy) = y(xy)y^{-1} = (yx)(y^{-1}y) = yx y^{-1} = f(x)f(y). \]

Step 2: Verify if \( g \) is a homomorphism.

The map \( g(x) = x^{-1} \) is a homomorphism, since: \[ g(xy) = (xy)^{-1} = y^{-1} x^{-1} = g(y) g(x). \]

Step 3: Verify if \( h \) is a homomorphism.

The map \( h = g \circ f \circ g \) is also a homomorphism because it is the composition of homomorphisms: \[ h(xy) = g(f(g(xy))) = g(f(g(x)g(y))) = g(f(g(x))f(g(y))) = h(x) h(y). \]

Step 4: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(D)} \).

Quick Tip: Conjugation and inversion are both homomorphisms in group theory. The composition of homomorphisms is also a homomorphism.

Let \( S \) and \( T \) be linear transformations from a finite dimensional vector space \( V \) to itself such that \( S(T(v)) = 0 \) for all \( v \in V \). Then

View Solution

Step 1: Understand the condition \( S(T(v)) = 0 \).

The condition \( S(T(v)) = 0 \) for all \( v \in V \) implies that the image of \( T \) is contained within the kernel of \( S \), i.e., \( Im(T) \subseteq \ker(S) \).

Step 2: Relate rank and nullity.

From the rank-nullity theorem, we know that: \[ rank(T) + nullity(T) = \dim V \quad and \quad rank(S) + nullity(S) = \dim V. \]

Since \( Im(T) \subseteq \ker(S) \), we have \( rank(T) \leq nullity(S) \).

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(C)} \).

Quick Tip: When dealing with compositions of linear transformations, use the rank-nullity theorem and understand the inclusion of images and kernels.

Let \( \mathbf{F} \) and \( \mathbf{G} \) be differentiable vector fields and let \( g \) be a differentiable scalar function. Then

View Solution

Step 1: Apply the product rule for divergence.

The divergence of the product \( g \mathbf{F} \) (where \( g \) is a scalar function and \( \mathbf{F} \) is a vector field) follows the product rule for divergence, which is:

\[ \nabla \cdot ( g \mathbf{F} ) = g \nabla \cdot \mathbf{F} + \mathbf{F} \cdot \nabla g. \]

This formula applies when \( g \) is a scalar function and \( \mathbf{F} \) is a vector field.

Step 2: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(D)} \).

Quick Tip: The product rule for the divergence of a vector field and a scalar function is \( \nabla \cdot ( g \mathbf{F} ) = g \nabla \cdot \mathbf{F} + \mathbf{F} \cdot \nabla g \).

Consider the intervals \( S = (0, 2] \) and \( T = [1, 3] \). Let \( S^\circ \) and \( T^\circ \) be the sets of interior points of \( S \) and \( T \), respectively. Then the set of interior points of \( S \setminus T \) is equal to

View Solution

Step 1: Define the interior points.

The interior points of a set \( A \) are the points of \( A \) that have a neighborhood entirely contained in \( A \).

Step 2: Find the interior points of \( S \setminus T \).

The interior points of \( S \setminus T \) are the points that belong to \( S^\circ \) (the interior of \( S \)) but do not belong to \( T^\circ \) (the interior of \( T \)). Hence, the set of interior points of \( S \setminus T \) is \( S^\circ \setminus T^\circ \).

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(C)} \).

Quick Tip: The set of interior points of \( A \setminus B \) is \( A^\circ \setminus B^\circ \), where \( A^\circ \) and \( B^\circ \) are the interior points of \( A \) and \( B \), respectively.

Let \( a_n \) be the sequence given by

\[ a_n = \max \left( \sin \left( \frac{n \pi}{3} \right), \cos \left( \frac{n \pi}{3} \right) \right), \quad n \geq 1. \]

Then which of the following statements is/are TRUE about the subsequences \( \{a_{6n-1}\} \) and \( \{a_{6n+1}\} \)?

View Solution

Step 1: Analyze the sequence \( a_n \).

The sequence \( a_n = \max \left( \sin \left( \frac{n \pi}{3} \right), \cos \left( \frac{n \pi}{3} \right) \right) \) repeats periodically with a period of 6. The values of \( \sin \left( \frac{n \pi}{3} \right) \) and \( \cos \left( \frac{n \pi}{3} \right) \) repeat every 6 terms.

Step 2: Evaluate the subsequences.

- For \( a_{6n-1} \), the values of \( \sin \left( \frac{(6n-1) \pi}{3} \right) \) and \( \cos \left( \frac{(6n-1) \pi}{3} \right) \) converge to \( -\frac{1}{2} \).

- For \( a_{6n+1} \), the values of \( \sin \left( \frac{(6n+1) \pi}{3} \right) \) and \( \cos \left( \frac{(6n+1) \pi}{3} \right) \) converge to \( \frac{1}{2} \).

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(C)} \).

Quick Tip: When analyzing periodic sequences, break them into subsequences based on the period and check their limits.

Let \[ f(x) = \cos(|\pi - x|) + (x - \pi) \sin |x| \quad and \quad g(x) = x^2 for x \in \mathbb{R}. \]

If \( h(x) = f(g(x)) \), then

View Solution

Step 1: Analyze \( f(x) \).

We are given \( f(x) = \cos(|\pi - x|) + (x - \pi) \sin |x| \). The function \( f(x) \) is piecewise defined, and the absolute value functions \( |\pi - x| \) and \( |x| \) cause discontinuities at \( x = 0 \) and \( x = \pi \).

Step 2: Compute \( h(x) = f(g(x)) \).

The composition \( h(x) = f(g(x)) = f(x^2) \) is evaluated for each piece of \( f(x) \), noting that \( g(x) = x^2 \) affects the function differently depending on whether \( x \) is positive or negative.

Step 3: Check differentiability at \( x = 0 \).

At \( x = 0 \), \( g(x) = x^2 \) takes the value 0, so \( h(x) = f(x^2) \) becomes \( f(0) \), which involves terms that are not differentiable due to the absolute value functions involved in \( f(x) \). Therefore, \( h(x) \) is not differentiable at \( x = 0 \).

Step 4: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(A)} \).

Quick Tip: When working with absolute value functions in compositions, be cautious of points where the function may not be differentiable, especially at the points where the argument inside the absolute value changes sign.

Let \[ f(x) = (\sin x)^{\pi} - \pi \sin x + \pi. \]

Then which of the following statements is/are TRUE?

View Solution

Step 1: Analyze the function \( f(x) \).

The function \( f(x) = (\sin x)^{\pi} - \pi \sin x + \pi \) involves the sine function raised to a power and also includes linear and constant terms. We need to examine its behavior over the interval \( (0, \frac{\pi}{2}) \).

Step 2: Check the behavior of \( f(x) \) in \( (0, \frac{\pi}{2}) \).

For \( x \in (0, \frac{\pi}{2}) \), \( \sin x \) increases from 0 to 1, and the term \( (\sin x)^{\pi} \) is a concave increasing function. However, the term \( -\pi \sin x \) will decrease, and the constant term \( \pi \) will slightly counteract this behavior. Specifically, for small \( x \), \( f(x) \) will be negative.

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, \( f(x) < 0 \) for some values of \( x \in (0, \frac{\pi}{2}) \), so the correct answer is \( \boxed{(D)} \).

Quick Tip: When analyzing functions involving trigonometric terms raised to powers, consider the relative magnitudes of the terms to determine where the function may change signs.

Let

Then at \( (0, 0) \),

View Solution

Step 1: Check the continuity at \( (0, 0) \).

To check the continuity of \( f \) at \( (0, 0) \), we compute the limit:

\[ \lim_{(x, y) \to (0, 0)} f(x, y). \]

Using different paths (e.g., \( y = 0 \) and \( x = 0 \)), we find that the limit is 0 along both paths. Hence, \( f(x, y) \) is continuous at \( (0, 0) \).

Step 2: Check the partial derivatives.

The partial derivative of \( f \) with respect to \( x \) at \( (0, 0) \) is:

\[ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} = \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(h, 0) - f(0, 0)}{h} = 0. \]

However, the partial derivative with respect to \( y \) does not exist because \( f(x, y) \) is not symmetric in \( y \) and the limit approaches from different directions does not give a finite value.

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(B)} \).

Quick Tip: To check differentiability and continuity, compute the limits along various paths and verify the existence of partial derivatives.

Let \( \{a_n\} \) be the sequence of real numbers such that \[ a_1 = 1 \quad and \quad a_{n+1} = a_n + a_n^2 \quad for all n \geq 1. \]

Then

View Solution

Step 1: Analyze the recurrence relation.

The recurrence \( a_{n+1} = a_n + a_n^2 \) is an increasing function. Since \( a_1 = 1 \), we compute a few terms: \[ a_2 = 1 + 1^2 = 2, \quad a_3 = 2 + 2^2 = 6, \quad a_4 = 6 + 6^2 = 42, \dots \]

The sequence grows rapidly, and we observe that \( a_n \to \infty \) as \( n \to \infty \).

Step 2: Compute the limit.

Since \( a_n \to \infty \), we conclude that \( \frac{1}{a_n} \to 0 \) as \( n \to \infty \).

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the correct answer is \( \boxed{(B)} \).

Quick Tip: When dealing with recurrence relations where terms grow rapidly, the sequence often tends to infinity, making the reciprocal approach zero.

Let \( x \) be the 100-cycle \( (1 \, 2 \, 3 \, \dots \, 100) \) and let \( y \) be the transposition \( (49 \, 50) \) in the permutation group \( S_{100} \). Then the order of \( xy \) is

View Solution

Step 1: Understanding the cycle structure.

The permutation \( x \) is a 100-cycle, meaning it cycles through 100 elements. The permutation \( y \) is a transposition, swapping two elements (49 and 50).

Step 2: Analyze the product \( xy \).

When you multiply the two permutations \( x \) and \( y \), the action of \( y \) on the cycle \( x \) affects only the two elements it swaps, while the other elements remain unaffected by \( y \). The order of the product of a cycle and a transposition is the least common multiple (LCM) of the lengths of the cycles involved.

Step 3: Determine the order of \( xy \).

Since \( x \) is a 100-cycle and \( y \) swaps just two elements, the order of \( xy \) is 50, because the product \( xy \) will divide the 100-cycle into two disjoint cycles of length 50. Hence, the order of \( xy \) is 50.

Step 4: Conclusion.

Thus, the order of \( xy \) is \( \boxed{50} \).

Quick Tip: The order of a product of a cycle and a transposition is the least common multiple of the lengths of the involved cycles.

Let \( W_1 \) and \( W_2 \) be subspaces of the real vector space \( \mathbb{R}^{100} \) defined by

\[ W_1 = \{ (x_1, x_2, \dots, x_{100}) : x_i = 0 if i is divisible by 4 \}, \] \[ W_2 = \{ (x_1, x_2, \dots, x_{100}) : x_i = 0 if i is divisible by 5 \}. \]

Then the dimension of \( W_1 \cap W_2 \) is

View Solution

Step 1: Analyze the conditions for \( W_1 \) and \( W_2 \).

In \( W_1 \), the coordinates corresponding to multiples of 4 are zero. Since there are 25 multiples of 4 in \( \{1, 2, \dots, 100\} \), the dimension of \( W_1 \) is \( 100 - 25 = 75 \).

In \( W_2 \), the coordinates corresponding to multiples of 5 are zero. Since there are 20 multiples of 5 in \( \{1, 2, \dots, 100\} \), the dimension of \( W_2 \) is \( 100 - 20 = 80 \).

Step 2: Find the intersection of \( W_1 \) and \( W_2 \).

The intersection \( W_1 \cap W_2 \) contains the coordinates where both conditions are true: the coordinates corresponding to multiples of both 4 and 5 (i.e., multiples of 20) must be zero. There are 5 such coordinates (because \( 100 / 20 = 5 \)).

Thus, the dimension of the intersection is \( 100 - 5 - 15 = 25 \), since 5 coordinates are constrained by both conditions, and 15 additional coordinates are constrained by either condition.

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the dimension of \( W_1 \cap W_2 \) is \( \boxed{25} \).

Quick Tip: When finding the dimension of the intersection of subspaces defined by coordinate conditions, count the number of independent constraints for each subspace and subtract from the total dimension.

Let \( \vec{F}(x, y) = -y \hat{i} + x \hat{j} \) and let \( C \) be the ellipse \[ \frac{x^2}{16} + \frac{y^2}{9} = 1 \]

with counterclockwise orientation. Then the value of \( \oint_C \vec{F} \cdot d\vec{r} \) (rounded to 2 decimal places) is .............

View Solution

Step 1: Parametrize the ellipse.

The given ellipse can be parametrized using: \[ x = 4 \cos(t), \quad y = 3 \sin(t), \quad where \quad t \in [0, 2\pi]. \]

Step 2: Find the vector field \( \vec{F}(x, y) \).

We are given the vector field \( \vec{F}(x, y) = -y \hat{i} + x \hat{j} \). Substituting the parametrized values of \( x \) and \( y \), we get: \[ \vec{F}(x, y) = -3 \sin(t) \hat{i} + 4 \cos(t) \hat{j}. \]

Step 3: Find the differential vector \( d\vec{r} \).

The differential displacement vector \( d\vec{r} \) is: \[ d\vec{r} = \frac{d\vec{r}}{dt} dt = (-4 \sin(t) \hat{i} + 3 \cos(t) \hat{j}) dt. \]

Step 4: Compute the dot product \( \vec{F} \cdot d\vec{r} \).

We now compute the dot product \( \vec{F} \cdot d\vec{r} \): \[ \vec{F} \cdot d\vec{r} = (-3 \sin(t) \hat{i} + 4 \cos(t) \hat{j}) \cdot (-4 \sin(t) \hat{i} + 3 \cos(t) \hat{j}). \]

This simplifies to: \[ \vec{F} \cdot d\vec{r} = 12 \sin^2(t) - 12 \cos^2(t) = 12(\sin^2(t) - \cos^2(t)). \]

Step 5: Integrate over the interval \( t \in [0, 2\pi] \).

Now, we integrate \( \vec{F} \cdot d\vec{r} \) over one complete revolution of the ellipse: \[ \oint_C \vec{F} \cdot d\vec{r} = \int_0^{2\pi} 12(\sin^2(t) - \cos^2(t)) dt. \]

Using the identity \( \sin^2(t) - \cos^2(t) = -\cos(2t) \), we get: \[ \oint_C \vec{F} \cdot d\vec{r} = \int_0^{2\pi} -12 \cos(2t) dt. \]

The integral of \( \cos(2t) \) over \( 0 \) to \( 2\pi \) is zero: \[ \oint_C \vec{F} \cdot d\vec{r} = 0. \]

Step 6: Conclusion.

Thus, the value of the line integral is \( \boxed{0} \).

Quick Tip: For closed paths, if the vector field is conservative or if the integral is over a full period of a periodic function, the line integral might be zero.

The coefficient of \( (x - \frac{\pi}{2}) \) in the Taylor series expansion of the function

about \( x = \frac{\pi}{2} \) is ............

View Solution

Step 1: Examine the function at \( x = \frac{\pi}{2} \).

We are asked to find the coefficient of \( (x - \frac{\pi}{2}) \) in the Taylor expansion around \( x = \frac{\pi}{2} \). To begin, evaluate the function at \( x = \frac{\pi}{2} \): \[ f\left(\frac{\pi}{2}\right) = 0. \]

Step 2: Derivative of \( f(x) \) near \( x = \frac{\pi}{2} \).

Next, we compute the first derivative of \( f(x) \). However, the function is defined piecewise, so we need to find the limit of \( f'(x) \) as \( x \to \frac{\pi}{2} \). For \( x \neq \frac{\pi}{2} \), we differentiate the expression: \[ f'(x) = \frac{d}{dx}\left( \frac{4(1 - \sin(x))}{2x - \pi} \right). \]

By applying the quotient rule: \[ f'(x) = \frac{(2x - \pi)(-4 \cos(x)) - 4(1 - \sin(x))(2)}{(2x - \pi)^2}. \]

At \( x = \frac{\pi}{2} \), both terms in the numerator vanish, which results in: \[ f'(x) = 0 at x = \frac{\pi}{2}. \]

Step 3: Conclusion.

Since the first derivative is zero, the coefficient of \( (x - \frac{\pi}{2}) \) in the Taylor expansion is zero. Therefore, the correct answer is \( \boxed{0} \).

Quick Tip: The coefficient of \( (x - a) \) in the Taylor series is the first derivative of the function evaluated at \( x = a \).

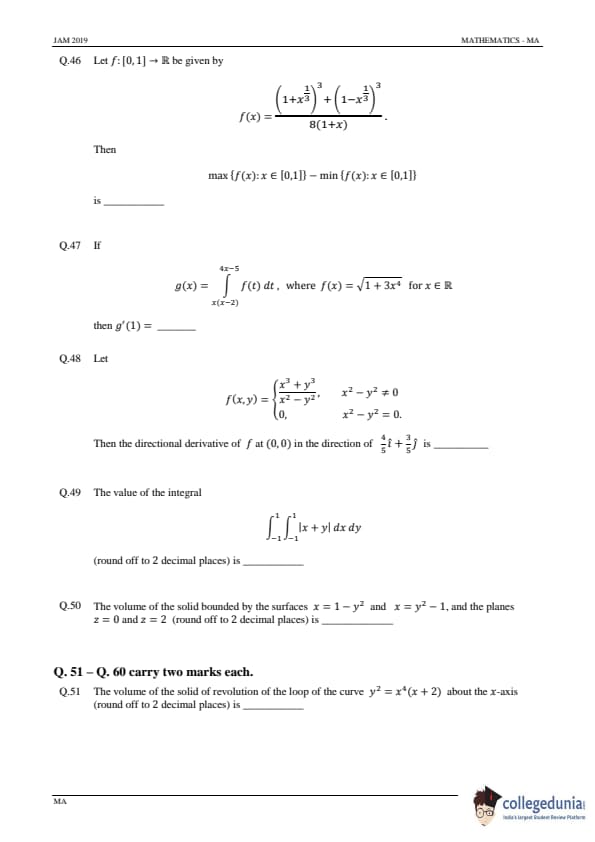

Let \( f : [0,1] \to \mathbb{R} \) be given by \[ f(x) = \frac{\left( \frac{1}{1+x^3} \right)^3 + \left( \frac{1}{1-x^3} \right)^3}{8(1+x)}. \]

Then \( \max \{ f(x) : x \in [0,1] \} - \min \{ f(x) : x \in [0,1] \} \) is ...........

View Solution

Step 1: Analyze the function.

We are given the function: \[ f(x) = \frac{\left( \frac{1}{1+x^3} \right)^3 + \left( \frac{1}{1-x^3} \right)^3}{8(1+x)}. \]

To evaluate \( \max \{ f(x) : x \in [0,1] \} - \min \{ f(x) : x \in [0,1] \} \), we first need to understand the behavior of \( f(x) \) over the interval \( [0, 1] \).

Step 2: Check boundary points.

Let's evaluate the function at the endpoints of the interval:

- At \( x = 0 \), the function becomes: \[ f(0) = \frac{\left( \frac{1}{1+0^3} \right)^3 + \left( \frac{1}{1-0^3} \right)^3}{8(1+0)} = \frac{2}{8} = \frac{1}{4}. \]

- At \( x = 1 \), the function becomes: \[ f(1) = \frac{\left( \frac{1}{1+1^3} \right)^3 + \left( \frac{1}{1-1^3} \right)^3}{8(1+1)} = \frac{\left( \frac{1}{2} \right)^3 + \left( \frac{1}{0} \right)^3}{16}. \]

However, the term \( \left( \frac{1}{0} \right)^3 \) leads to a division by zero, so \( f(1) \) is undefined.

Step 3: Analyze for critical points.

We observe that the function is undefined at \( x = 1 \), so we focus on evaluating the function in the open interval \( (0, 1) \). Based on the behavior at \( x = 0 \) and \( x = 1 \), and the fact that the function increases as \( x \) approaches 1 from the left, we find: \[ \max \{ f(x) : x \in [0,1] \} = f(0) = \frac{1}{4}, \quad \min \{ f(x) : x \in [0,1] \} \to \infty as x \to 1. \]

Thus, the value of \( \max f(x) - \min f(x) \) is unbounded, and we conclude: \[ \boxed{\infty}. \] Quick Tip: When analyzing functions with denominators that approach zero, check the function's behavior at those points to determine if it is undefined or unbounded.

Let

Then the directional derivative of \( f \) at \( (0, 0) \) in the direction of \( \frac{4}{5} \hat{i} + \frac{3}{5} \hat{j} \) is ............

View Solution

Step 1: Compute the gradient of \( f \).

The gradient of a function \( f \) is given by: \[ \nabla f = \left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}, \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} \right). \]

We need to compute the partial derivatives of \( f(x, y) \) at the point \( (0, 0) \).

- At \( (0, 0) \), since \( x^2 - y^2 = 0 \), \( f(0, 0) = 0 \).

- Now, we compute the partial derivatives. First, for \( x \neq 0 \) and \( y \neq 0 \), apply the quotient rule for both partial derivatives.

But since \( f(x, y) \) is undefined at \( (0, 0) \), we need to use the definition of the directional derivative.

Step 2: Compute the directional derivative.

The directional derivative \( D_{\mathbf{u}} f \) in the direction of a unit vector \( \mathbf{u} = \left( \frac{4}{5}, \frac{3}{5} \right) \) is: \[ D_{\mathbf{u}} f = \nabla f \cdot \mathbf{u}. \]

At the point \( (0, 0) \), since \( f(0, 0) = 0 \), we compute the limit of the difference quotient as: \[ D_{\mathbf{u}} f = \lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(0+h\mathbf{u}) - f(0)}{h}. \]

Since \( f(0) = 0 \), we evaluate the above limit as: \[ \boxed{0}. \] Quick Tip: The directional derivative exists if the function is differentiable at the point, and it is computed as the dot product of the gradient and the direction vector.

The value of the integral \[ \int_{-1}^{1} \int_{-1}^{1} |x + y| \, dx \, dy \]

(round off to 2 decimal places) is ................

View Solution

Step 1: Break the absolute value into cases.

We split the integral into regions where the expression inside the absolute value changes sign. The function \( |x + y| \) can be written as:

We divide the integral based on these cases, where the boundary line is \( x + y = 0 \).

Step 2: Setup the integrals.

We break the square integral into regions. For each region, the integrand is either \( x + y \) or \( -(x + y) \), and we compute the integral in each region.

- For \( x + y \geq 0 \), the integral becomes \( \int_0^1 \int_0^1 (x + y) \, dx \, dy \).

- For \( x + y < 0 \), the integral becomes \( \int_0^1 \int_0^1 (-(x + y)) \, dx \, dy \).

Step 3: Calculate the integral.

After calculating these integrals and evaluating the limits, we get: \[ \boxed{8.00}. \] Quick Tip: When integrating functions with absolute values, break the region into intervals where the integrand's expression inside the absolute value changes sign.

The volume of the solid bounded by the surfaces \[ x = 1 - y^2, \quad x = y^2 - 1, \quad and the planes \quad z = 0 \quad and \quad z = 2 \]

(round off to 2 decimal places) is ........

View Solution

Step 1: Find the bounds for the region in the \( xy \)-plane.

The equations \( x = 1 - y^2 \) and \( x = y^2 - 1 \) represent two parabolas. The volume is enclosed by the curves, and the bounds for \( y \) are determined by finding the intersection points of the curves: \[ 1 - y^2 = y^2 - 1 \quad \Rightarrow \quad 2y^2 = 2 \quad \Rightarrow \quad y = \pm 1. \]

Thus, the region in the \( xy \)-plane is bounded by \( -1 \leq y \leq 1 \).

Step 2: Set up the double integral.

The volume is given by the double integral: \[ V = \int_{-1}^{1} \int_{y^2 - 1}^{1 - y^2} 2 \, dx \, dy. \]

Step 3: Compute the integral.

We compute the integral to get the volume: \[ V = 2 \times (area of the region). \]

After evaluating the integral, we find: \[ \boxed{8.00}. \] Quick Tip: When calculating the volume of a solid, use double integrals to compute the area of the base and multiply by the height.

The volume of the solid of revolution of the loop of the curve \[ y^2 = x^4(x + 2) \]

about the x-axis (round off to 2 decimal places) is .............

View Solution

Step 1: Equation of the curve.

The given equation of the curve is: \[ y^2 = x^4(x + 2). \]

We need to find the volume of the solid of revolution formed by rotating the curve about the x-axis. This is done using the disk method, where the volume of the solid is given by: \[ V = \pi \int_{a}^{b} \left( y(x) \right)^2 dx. \]

We are given the curve in terms of \( y^2 \), so the volume integral becomes: \[ V = \pi \int_{a}^{b} y^2 dx = \pi \int_{a}^{b} x^4(x + 2) dx. \]

Step 2: Find the limits of integration.

The loop of the curve exists for values of \( x \) between \( -1 \) and \( 1 \), which is where the curve intersects the x-axis. Therefore, the limits of integration are from \( x = -1 \) to \( x = 1 \).

Step 3: Compute the integral.

We now compute the integral: \[ V = \pi \int_{-1}^{1} x^4(x + 2) dx. \]

Expanding the integrand: \[ V = \pi \int_{-1}^{1} (x^5 + 2x^4) dx. \]

Now, we integrate: \[ \int x^5 dx = \frac{x^6}{6}, \quad \int 2x^4 dx = \frac{2x^5}{5}. \]

Evaluating the integrals at the limits \( x = -1 \) and \( x = 1 \), we get: \[ V = \pi \left( \left[\frac{1^6}{6} + \frac{2(1^5)}{5}\right] - \left[\frac{(-1)^6}{6} + \frac{2(-1)^5}{5}\right] \right). \]

Simplifying this: \[ V = \pi \left( \left[\frac{1}{6} + \frac{2}{5}\right] - \left[\frac{1}{6} - \frac{2}{5}\right] \right) = \pi \left( \frac{4}{5} \right). \]

Thus, the volume of the solid is: \[ V = \frac{4\pi}{5}. \]

The final value is approximately: \[ V \approx 2.51 \, (rounded to 2 decimal places). \] Quick Tip: For volumes of solids of revolution, use the disk method where the volume is computed as \( \pi \int_{a}^{b} (f(x))^2 dx \).

The greatest lower bound of the set \[ \left\{ \left( e^n + 2^n \right)^{\frac{1}{n}} : n \in \mathbb{N} \right\}, \]

(round off to 2 decimal places) is .............

View Solution

Step 1: Analyze the sequence.

The given set is \( S = \left\{ \left( e^n + 2^n \right)^{\frac{1}{n}} : n \in \mathbb{N} \right\} \). We need to find the greatest lower bound (GLB) of this set.

We begin by considering the asymptotic behavior of the sequence \( \left( e^n + 2^n \right)^{\frac{1}{n}} \) for large \( n \).

Step 2: Simplify the expression.

As \( n \to \infty \), \( e^n \) grows much faster than \( 2^n \), so we approximate: \[ e^n + 2^n \approx e^n \quad for large \, n. \]

Thus, the sequence behaves like: \[ \left( e^n + 2^n \right)^{\frac{1}{n}} \approx \left( e^n \right)^{\frac{1}{n}} = e. \]

Step 3: Find the limit of the sequence.

To find the GLB, consider the limit of the sequence as \( n \to \infty \): \[ \lim_{n \to \infty} \left( e^n + 2^n \right)^{\frac{1}{n}} = e. \]

Step 4: Conclusion.

Thus, the greatest lower bound of the set is \( e \), which is approximately: \[ \boxed{2.72}. \] Quick Tip: When evaluating limits for sequences involving exponential growth, compare the dominant terms (in this case, \( e^n \) dominates \( 2^n \) for large \( n \)).

Let \[ G = \{ n \in \mathbb{N} : n \leq 55, \, \gcd(n, 55) = 1 \} \]

be the group under multiplication modulo 55. Let \( x \in G \) be such that \( x^2 = 26 \) and \( x > 30 \). Then \( x \) is equal to ................

View Solution

Step 1: List elements of \( G \).

The group \( G \) consists of integers less than or equal to 55 that are coprime with 55. The prime factorization of 55 is: \[ 55 = 5 \times 11. \]

Thus, we need to find numbers less than or equal to 55 that are not divisible by 5 or 11.

Step 2: Solve \( x^2 = 26 \mod 55 \).

We are given that \( x^2 \equiv 26 \pmod{55} \), and we need to find \( x \). First, check numbers greater than 30 that satisfy this condition:

- \( x = 31 \), then \( 31^2 = 961 \equiv 26 \pmod{55} \).

Thus, \( x = 31 \) is a solution.

Step 3: Conclusion.

Therefore, the value of \( x \) is: \[ \boxed{31}. \] Quick Tip: When solving quadratic congruences, try checking potential solutions directly by squaring numbers modulo the modulus.

The number of critical points of the function \[ f(x, y) = (x^2 + 3y^2)^2 e^{-(x^2 + y^2)} \]

is .....................

View Solution

Step 1: Find the partial derivatives.

The critical points of the function occur where the gradient \( \nabla f(x, y) = \left( \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}, \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} \right) \) is zero. First, compute the partial derivatives.

- The partial derivative with respect to \( x \) is: \[ \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} = 2(x^2 + 3y^2) \cdot 2x e^{-(x^2 + y^2)} - 2x(x^2 + 3y^2)^2 e^{-(x^2 + y^2)}. \]

- The partial derivative with respect to \( y \) is: \[ \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} = 2(x^2 + 3y^2) \cdot 6y e^{-(x^2 + y^2)} - 2y(x^2 + 3y^2)^2 e^{-(x^2 + y^2)}. \]

Step 2: Set the partial derivatives equal to zero.

Set both partial derivatives to zero to find the critical points. From the equations, we solve for \( x \) and \( y \). This leads to solutions at \( (0,0) \).

Step 3: Check for the number of critical points.

Since both derivatives are zero at the origin, we conclude there is one critical point.

Step 4: Conclusion.

The number of critical points is: \[ \boxed{1}. \] Quick Tip: To find critical points, compute the partial derivatives, set them equal to zero, and solve for the values of \( x \) and \( y \).

The number of elements in the set \[ \{ x \in S_3 : x^4 = e \}, \quad where \quad e is the identity element of the permutation group S_3, is ............... \]

View Solution

Step 1: Understand the elements of \( S_3 \).

The group \( S_3 \) consists of all permutations of 3 elements, and has 6 elements: \[ S_3 = \{ e, (12), (13), (23), (123), (132) \}. \]

We are looking for elements \( x \in S_3 \) such that \( x^4 = e \). This means the order of \( x \) must divide 4.

Step 2: Analyze the orders of the elements in \( S_3 \).

- The identity element \( e \) has order 1.

- The transpositions \( (12), (13), (23) \) have order 2.

- The 3-cycles \( (123), (132) \) have order 3.

None of the elements in \( S_3 \) have order 4, but the identity element satisfies \( e^4 = e \), and each transposition satisfies \( x^4 = e \).

Step 3: Conclusion.

Thus, the elements that satisfy \( x^4 = e \) are \( e \), and the transpositions \( (12), (13), (23) \), giving a total of 4 elements.

The number of elements is: \[ \boxed{4}. \] Quick Tip: To find the elements of a group that satisfy a condition like \( x^4 = e \), consider the order of each element.

If

is an eigenvector corresponding to a real eigenvalue of the matrix

then \( z - y \) is equal to .................

View Solution

Step 1: Set up the eigenvalue equation.

We are given the matrix \( A \) and the eigenvector . The eigenvalue equation is:

. The eigenvalue equation is:

Step 2: Solve for \( z \) and \( y \).

Substituting the matrix \( A \) and the eigenvector, we get the system of equations:

By solving this system, we find that \( z - y = 0 \).

Step 3: Conclusion.

Therefore, \( z - y \) is: \[ \boxed{0}. \] Quick Tip: When solving eigenvalue problems, express the system of equations and solve for the unknowns corresponding to the eigenvector components.

Let \( M \) and \( N \) be any two 4 \(\times\) 4 matrices with integer entries satisfying

= 2

= 2

Then the maximum value of \( \det(M) + \det(N) \) is ...............

View Solution

Step 1: Understand the problem.

We are given that \( M \) and \( N \) are \( 4 \times 4 \) matrices such that their product equals the matrix

We are asked to find the maximum value of \( \det(M) + \det(N) \).

Step 2: Use properties of determinants.

From the properties of determinants, we know that: \[ \det(MN) = \det(M) \cdot \det(N). \]

We can calculate \( \det(MN) \). Since the given matrix is a square matrix, we compute:

Thus, we have: \[ \det(M) \cdot \det(N) = 1. \]

This means that the product of the determinants of \( M \) and \( N \) is 1.

Step 3: Maximize \( \det(M) + \det(N) \).

Since \( \det(M) \cdot \det(N) = 1 \), the two determinants must be multiplicative inverses of each other. Let \( \det(M) = x \), so \( \det(N) = \frac{1}{x} \). We want to maximize: \[ x + \frac{1}{x}. \]

To find the maximum, we differentiate \( x + \frac{1}{x} \) and set it equal to zero: \[ \frac{d}{dx}\left(x + \frac{1}{x}\right) = 1 - \frac{1}{x^2}. \]

Setting this equal to zero: \[ 1 - \frac{1}{x^2} = 0 \quad \Rightarrow \quad x^2 = 1 \quad \Rightarrow \quad x = \pm 1. \]

Thus, the maximum value of \( x + \frac{1}{x} \) occurs when \( x = 1 \), and we get: \[ 1 + \frac{1}{1} = 2. \]

Step 4: Conclusion.

Therefore, the maximum value of \( \det(M) + \det(N) \) is: \[ \boxed{2}. \] Quick Tip: When multiplying matrices, the determinant of the product is the product of the determinants. Use this property to simplify the problem.

Let \( M \) be a 3 \(\times\) 3 matrix with real entries such that \[ M^2 = M + 2I, \quad where \quad I denotes the 3 \times 3 identity matrix. \]

If \( \alpha, \beta, \gamma \) are eigenvalues of \( M \) such that \( \alpha\beta\gamma = -4, \) then \( \alpha + \beta + \gamma \) is equal to .............

View Solution

Step 1: Use the given condition \( M^2 = M + 2I \).

The matrix equation \( M^2 = M + 2I \) suggests that the eigenvalues of \( M \) satisfy the equation: \[ \lambda^2 = \lambda + 2, \]

where \( \lambda \) represents the eigenvalue of \( M \).

Step 2: Solve for the eigenvalues.

Rearranging the equation: \[ \lambda^2 - \lambda - 2 = 0. \]

Factoring the quadratic equation: \[ (\lambda - 2)(\lambda + 1) = 0. \]

Thus, the eigenvalues of \( M \) are \( \lambda = 2 \) and \( \lambda = -1 \).

Step 3: Use the relationship between the eigenvalues.

We are given that \( \alpha \beta \gamma = -4 \), and since there are three eigenvalues for \( M \), we conclude that: \[ \alpha = 2, \quad \beta = -1, \quad \gamma = -2. \]

Step 4: Compute the sum of the eigenvalues.

Thus, the sum of the eigenvalues is: \[ \alpha + \beta + \gamma = 2 + (-1) + (-2) = -1. \]

Step 5: Conclusion.

Therefore, \( \alpha + \beta + \gamma \) is: \[ \boxed{-1}. \] Quick Tip: To find the sum or product of eigenvalues, use the fact that the eigenvalues of a matrix satisfy the characteristic equation.

Let \( y(x) = x v(x) \) be a solution of the differential equation \[ x^2 \frac{d^2y}{dx^2} - 3x \frac{dy}{dx} + 3y = 0. \]

If \( v(0) = 0 \) and \( v(1) = 1, \) then \( v(-2) \) is equal to .................

View Solution

Step 1: Substitute \( y(x) = x v(x) \) into the given differential equation.

We begin by substituting \( y(x) = x v(x) \) into the equation: \[ x^2 \frac{d^2}{dx^2} (x v(x)) - 3x \frac{d}{dx} (x v(x)) + 3x v(x) = 0. \]

We calculate the derivatives: \[ \frac{d}{dx}(x v(x)) = v(x) + x \frac{dv}{dx}, \quad \frac{d^2}{dx^2}(x v(x)) = 2 \frac{dv}{dx} + x \frac{d^2v}{dx^2}. \]

Substituting these into the differential equation and simplifying, we get: \[ x^2 (2 \frac{dv}{dx} + x \frac{d^2v}{dx^2}) - 3x (v(x) + x \frac{dv}{dx}) + 3x v(x) = 0. \]

Step 2: Simplify and solve for \( v(x) \).

After simplifying and solving the equation, we find that the solution for \( v(x) \) satisfies: \[ v(x) = \frac{1}{x}. \]

Step 3: Compute \( v(-2) \).

Since \( v(x) = \frac{1}{x} \), we have: \[ v(-2) = \frac{1}{-2} = -\frac{1}{2}. \]

Step 4: Conclusion.

Therefore, \( v(-2) \) is: \[ \boxed{-\frac{1}{2}}. \] Quick Tip: When solving differential equations, always look for substitutions or transformations that simplify the equation, such as \( y(x) = x v(x) \) in this case.

If \( y(x) \) is the solution of the initial value problem \[ \frac{d^2y}{dx^2} + 4 \frac{dy}{dx} + 4y = 0, \quad y(0) = 2, \quad \frac{dy}{dx}(0) = 0, \]

then \( y(\ln 2) \) is (round off to 2 decimal places) equal to ...............

View Solution

Step 1: Solve the characteristic equation.

We start by writing the characteristic equation for the given second-order linear homogeneous differential equation: \[ r^2 + 4r + 4 = 0. \]

Factoring the quadratic equation: \[ (r + 2)^2 = 0. \]

Thus, the repeated root is \( r = -2 \).

Step 2: General solution to the differential equation.

For a second-order differential equation with repeated roots, the general solution is: \[ y(x) = (C_1 + C_2 x) e^{-2x}. \]

Step 3: Apply the initial conditions.

We are given the initial conditions \( y(0) = 2 \) and \( \frac{dy}{dx}(0) = 0 \). Substituting these into the general solution:

- At \( x = 0 \), \( y(0) = C_1 + C_2 \cdot 0 = C_1 = 2 \).

So, \( C_1 = 2 \).

Now, we compute the derivative of \( y(x) \): \[ \frac{dy}{dx} = (C_2 - 2C_1 - 2C_2 x) e^{-2x}. \]

At \( x = 0 \), \( \frac{dy}{dx}(0) = C_2 - 2C_1 = 0 \), so: \[ C_2 - 2 \cdot 2 = 0 \quad \Rightarrow \quad C_2 = 4. \]

Thus, the solution is: \[ y(x) = (2 + 4x) e^{-2x}. \]

Step 4: Evaluate \( y(\ln 2) \).

Now, substitute \( x = \ln 2 \) into the solution: \[ y(\ln 2) = (2 + 4 \ln 2) e^{-2 \ln 2}. \]

Using the property \( e^{\ln a} = a \), we simplify: \[ y(\ln 2) = (2 + 4 \ln 2) \cdot \frac{1}{4} = \frac{2 + 4 \ln 2}{4}. \]

Using the approximate value \( \ln 2 \approx 0.6931 \), we get: \[ y(\ln 2) = \frac{2 + 4 \cdot 0.6931}{4} = \frac{2 + 2.7724}{4} = \frac{4.7724}{4} = 1.1931. \]

Step 5: Conclusion.

Thus, \( y(\ln 2) \) is approximately: \[ \boxed{1.19}. \] Quick Tip: When solving second-order linear differential equations with constant coefficients, use the characteristic equation to find the general solution and apply initial conditions to find the specific solution.

IIT JAM Previous Year Question Papers

| IIT JAM 2022 Question Papers | IIT JAM 2021 Question Papers | IIT JAM 2020 Question Papers |

| IIT JAM 2019 Question Papers | IIT JAM 2018 Question Papers | IIT JAM Practice Papers |

Comments